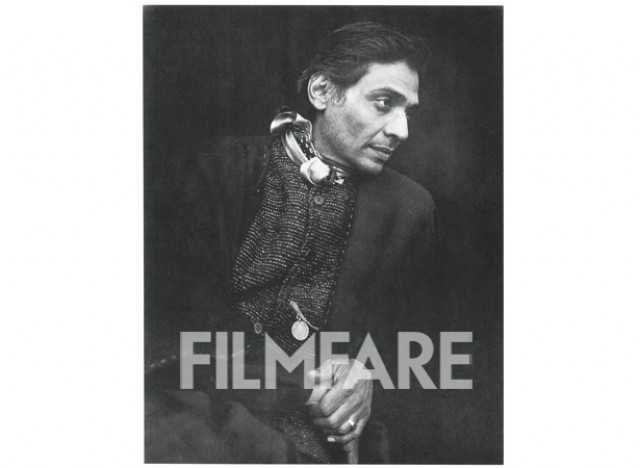

We know of monks who sold their Ferraris. But here’s the Raja of Kotwara, the erstwhile princely province on the outskirts of Lucknow, who shuns all reference to royalty. “The ‘r’ in royal should be replaced with ‘l’. I am ‘loyal’ to my roots – Awadh, Kotwara, Lucknow,” says filmmaker Muzaffar Ali whose films. His Gaman, Umrao Jaan, Anjuman and even his terminated Zooni, have carried the echoes and the ethos of pre-Partition India. “If you don’t look back there’s nothing to look forward to,” he explains. “I live my times in my films.”

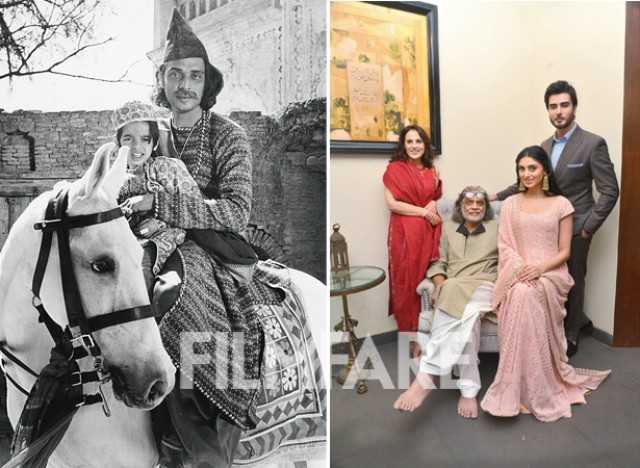

Decades later, he’s back with Jaanisaar, chronicling the love story of a courtesan and an Anglicised nawab set against the tumult of the 1857 Uprising. “I carry the pain of Lucknow, the music of Lucknow within me. The quaint city is changing. Every time I return from Lucknow, I’m both enriched and impoverished,” says he. “What we get today is electronic noise and crude body language. If you’re just a third rate version of the West why would people want to see you or your work?” he says explaining his obsession with ethnicity.

Interestingly, there’s more to Muzaffar Ali than films. Given his poetic sensibilities, he has nurtured the pain of abandoning his ambitious project Zooni, based on the Kashmiri poetess Habba Khatoon due to the insurgency in the valley. And that ache, he says, found its catharsis in the verses of mystical poet Amir Khusro, in the philosophy of Jalaluddin Rumi. It also inspired him to spearhead the annual Sufi festival, compose Sufi albums, make documentaries on the Sufi saints of India and launch Kotwara in a bid to revive the chikankari art and encourage women empowerment.

If Muzaffar owes his socialistic tendencies to his humanist father, the late Raja Sayyed Sajid Hussain, his mystical predisposition can be traced to his mother, Kaneez Hyder, a descendant of Baba Farid. The Padma Shri recipient is happy calling himself a Fakir who ‘accepts the spiritual gifts that life and people leave by’. In this journey of expressing the human predicament through aesthetics, wife and designer Meera has been his co-traveller. Here, he talks sabout his incessant romance with life…

Why I made jaanisar…

Through Jaanisar I’ve tried to retrieve a few pages of missing history - what happened in Awadh after the first war of Independence in 1857. Since then there’s been a consistent policy to divide the country – which eventually found expression in the Partition and is felt even today. Jaanisar is inspired by real-life instances. Like for instance my mother’s great grandfather was a freedom fighter and the governor of Muradabad. His body was burnt alive by the British and dragged along the streets, tied to elephants. The film is also centered on the romance between a Raja (Imran Abbas Naqvi) and a courtesan (Pernia Qureshi). The bhav and ada that Pernia brings to her role, her lyricism is unique. The song Hame bhi pyaar kar le, has been choreographed by the 86-year-old Kumudini Lakhiaji, who choreographed Rekha in Umrao Jaan (1982) three decades ago. The courtesan in Awadh was about culture. The British developed a phobia for dance and poetry as it united the Hindus and Muslims. Like Wajid Ali Shah (the last nawab of Awadh) often addressed Lord Krishna in his poetry. There was certain pathos about Wajid Ali Shah despite the indulgence associated with him. He was a great general.

why I was fascinated by Satyajit Ray…

Looking back, my tryst with cinema was destined. After my BSC, I took to geology (study of stones). Soon I realised patthar se toh nahin takra sakta! But seriously, there’s beauty in stones and I used that in my paintings. I also veered towards poetry. The works of poets Javed Kamal, Dr Rahi Masoom Reza and Shahryar (Akhlaq Mohammed Khan), cracked my mind.

In 1967, I went to Kolkata to attempt something creative. My father gave me a beautiful old car, an Isotta, which I sold to survive. I joined an advertising agency headed by Satyajit Ray. He had made a few films by then. He wore kurta-pyjama and smoked a pipe. I took to his personality. Poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay was a common friend and we ended up spending many evenings with Ray. He’d be playing the piano, sketching the costumes for his films... he was working on Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969). I was fascinated by his tone and tenor. Agar Ray na hote, toh Bengal ki koi identity nahin hoti. I wondered why we couldn’t give such an identity to Awadh.

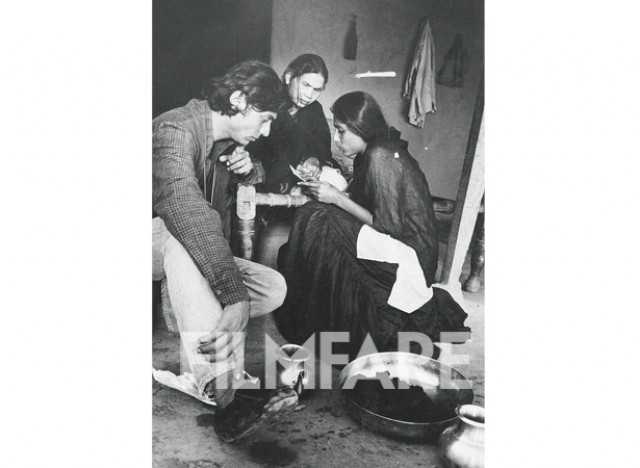

With Smita Patil on the set of Gaman

Why Smita Patil was enigmatic…

Later, I worked in the publicity department of Air India in Mumbai. The city gave me an insight into the plight of immigrants. I’ve somewhere inherited the socialist streak from my father Raja Sayyed Sajid Hussain. My father connected with the people of Kotwara and their problems. He was influenced by the philosophy of the Communist Party of Great Britain. My debut film Gaman (1978, starring Farooque Sheikh-Smita Patil) starts with my father typing ‘Kotwara’ on the typewriter. That was a tribute of sorts to him. The day Gaman released, my father sent a telegram, with these lines from the Bhagwad Gita, “Effort is thy duty; reward is not your concern!” This was when I had mortgaged my house to make the film!

Smita Patil was the most enigmatic personality. A woman’s eyes can hold a world. I used her eyes to tell a story. Also, Smita’s body language, the way she used her limbs, the way she wiped her nose with her dupatta was unique. With her, small things became big. She could say a lot without even uttering a word. Only Smita could show the helplessness of a woman, waiting for her husband.

On the other hand, Shabana Azmi is a cerebral actor. She brought a different pitch to her role of an activist in Anjuman (1986), which spotlighted the exploitation of chikan embroidery workers. The film talked about the fragile ethos of Lucknow being threatened. I used the language of the embroidery to convey the message. Satish Gujral (painter/writer), whose hearing was impaired those days, told me that it was the most beautiful film he had seen.

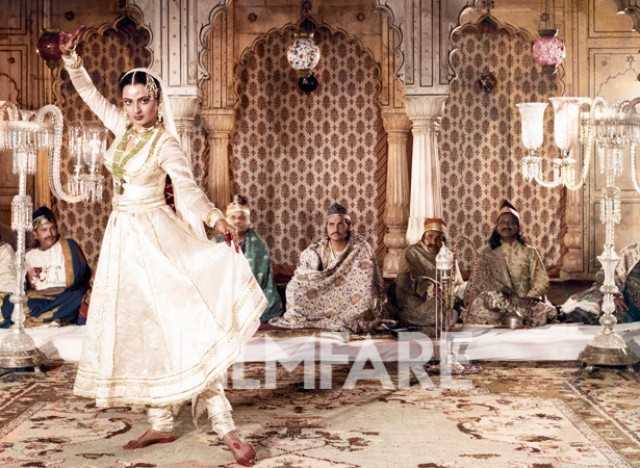

Rekha in Umrao Jaan

Why I shouldn’t have made umrao jaan…

When I was making Umrao Jaan (based on Umrao Jaan Ada, the 19th century courtesan/poetess in Lucknow), I believed it was something which would enter the bloodstream of the audiences. The lyrics, the music, Umrao’s graph as a girl and as a woman was riveting. I included the faded footprints of my childhood… the sunrise, the sunsets, the monsoon of Awadh… it was a nostalgic trip. Umrao was such a fascinating personality that even the maulvis couldn’t help looking at her! Rekha’s eyes mirrored a silent, resilient quality – gir kar sambhalne wali baat.

I give credit to all those who work with me. Hazrat Ali once said, “I’m a slave to anyone who has taught me even a word.” I’m a slave to all these creative people in my journey. Khayyam saab to ek nasha hai – he’s intoxication (Umrao Jaan gave classics like Dil cheez kya hai, Zindagi jab bhi, In aankhon ki masti). Jaidev saab ke saath bhi ek masti ka aalam tha – a state of creative ecstasy (Gaman gave gems like Aap ki yaad aati rahi, Seene mein jalan)! The raagmala Pratham dhar dhyan was written by Hazrat Amir Khusro (13th century mystic poet) in Umrao Jaan and so was Kahe ko byahe bides. Sometimes, I feel I shouldn’t have made Umrao Jaan (the film won two Filmfare Awards for Best Director and Best Music). I’m left competing with myself.

Why I was Heartbroken…

Zooni (began in 1988) was based on the folklore of the Kashmiri poet-empress Habba Khatoon known to people as Zooni. Dimple’s eyes could express the beauty, the helplessness which correlated to Kashmir. But while making Zooni, insurgency left me devastated. Zooni is a love story and it couldn’t thrive in strife. We abandoned the film in 1989. I returned heartbroken but not before leaving behind a bank balance of ‘goodwill’. I built a house there called the Zooni House. My toothbrush, my personal things are still there including my wounds…

Why I went beyond films…

After Zooni was shelved,

I went through great turmoil; even my paintings of those times express that lament. I immersed myself in Amir Khusro’s poetry. Then my father passed away in 1990. After that my temperament changed to fakiri (detachment). I went beyond films. I was fascinated by simple things like even the sight of buses going to Ajmer Sharief – the shrine of Hindalwali Khwaja Garib Nawaz.

I made a documentary on the saint titled Seena Ba Seena. Also my father’s comment, “Yahan koi nanga, bhookha na rahe…” referring to Kotwara inspired me to launch the Kotwara line which revived the legacy of chikan embroidery. A fakir gives you tabarruq (spiritual gift) through a word, a gesture… and your road changes. My father was a fakir in that sense.

In 2000, I launched Jahan-E-Khusro - the annual world Sufi Music Festival dedicated to Hazrat Amir Khusro. Singers from all over the world sing in an unblemished environment. I’ve also composed a few albums – Raqs-e-Bismil (ghazals inspired by 13th century Sufi mystic Jalaluddin Rumi) with Abida Parveen. It’s known to have helped terminally ill people face death peacefully. Paigham-e-Mohabbat had lyrics by Rahi Masoom Raza, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Ahmad Faraz among others. And through all this, my wife Meera has been with me. She’s the architect, the anchor of my life.

Why Rumi is relevant…

Some poetry brings you pain, some by enabling you to relate to your pain, eases the hurt… That’s why I seek solace in the work of Rumi. His message of love can help bridge the gap between the East and the West. His sense of submission, his surrender to his pir (master) Shams-e-Tabrizi… his tasawwuf (mysticism)… is inspiring.

I enjoy the simple things of life. Like I love animals, dogs, horses. I used to ride them but I believe they are too beautiful to ride. Above all, I’m a craftsman. I venture into woodwork, embroidery, durries... I hate anything driven by money. Funnily, the moment I keep money, I lose it. Barkat paise se nahin hoti, neeyat se hoti (abundance doesn’t come from wealth; it comes from your intent). Coming back to films, I can’t be told to make ‘a package’ of a film. I will only make what I know, what I have lived. I can’t make a Dabangg. Mujhe toh mera hi raasta chalna hai… no matter how winded. And if I can’t, maybe I’ll take to farming someday…

SHOW COMMENTS