- India

- International

Guns ‘n’ poses: The new crop of militants in Kashmir

They are young, educated and wealthy. And they love wielding their guns for the camera. Bashaarat Masood on the new crop of militants in the Valley. Photographs by Shuaib Masoodi

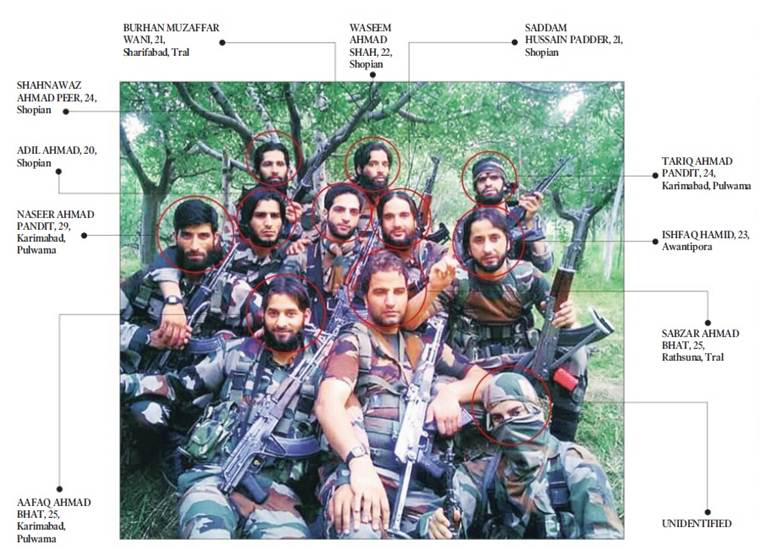

The new militants have begun releasing pictures and videos of themselves on social media, and this picture of 11 militants had gone viral.

The new militants have begun releasing pictures and videos of themselves on social media, and this picture of 11 militants had gone viral.

They called him Newton. He was bright and his name, Ishaq, was the Arabic version of the famous scientist’s first name, Isaac. He was among the best students in his school, having scored 98.4 per cent in Class X. His Class XII score, 85 per cent, was way lower, but for his friends in Laribal, a small village near the town of Tral in Kashmir’s Pulwama district, Ishaq remained Newton.

The 19-year-old was preparing to be a doctor and was studying for the common entrance test when he left home. His mother Rehti Begum calls him the “perfect boy” who would help his elder brothers in the fields, would object to his father speaking loudly on the phone and would never ask for money.

On March 16, “for the first time”, Ishaq asked his father, Mohammed Ismail Parray, a retired government employee, for money — Rs 1,000 to pay as fees at the computer centre he had joined. That was the last time they saw him. In April, the police informed them that Ishaq had joined the Hizbul Mujahideen.

Tral has emerged as a new major base

Tral has emerged as a new major base

In police records, Ishaq Ahmad Parray is one of 33 young men who have joined the ranks of militancy in the first six months of the year in the Valley, taking the total number of its active militants to 142. Of the 142, 54 are foreigners, mostly from Pakistan, and 88 are local youths. The latter, say the police, is the worrying part.

“The number of local militants has been steadily rising in the past several years, but in the last two years, there has been a sudden spurt. It is a concern because local militants elicit sympathy if they are killed or arrested. Besides, they know the topography better and have a large network of friends and relatives who act as couriers and transporters,” says a police officer.

At the onset of militancy in 1989, and till the mid-1990s, thousands of youths from the Valley had joined militant groups such as the Hizbul Mujahideen. After the mid-’90s, foreign militants, mostly Pakistani, formed the majority. After a lull of over a decade, militancy is slowly making a return, but this time with more locals than foreigners.

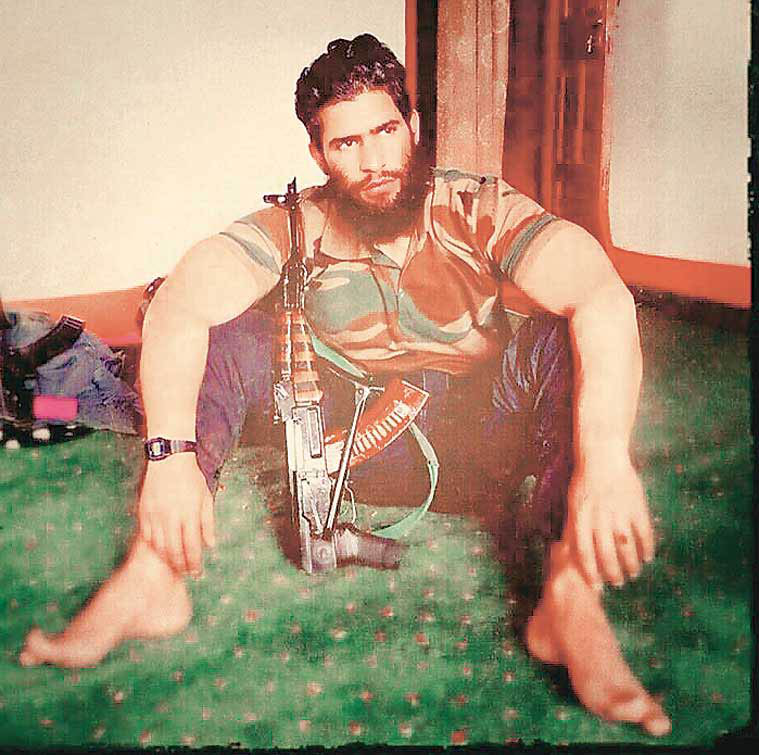

Zakir Rashid Bhat was an engineering student before he left home and joined the Hizbul Mujahideen

Zakir Rashid Bhat was an engineering student before he left home and joined the Hizbul Mujahideen

The casualties inflicted are few — five soldiers, three policemen and three civilians in the last one year — but the police say they are not taking any chances. For, the new crop is unlike the old. Unlike his armed predecessor who worked “over the ground” — performing peripheral tasks such as transporting guns, for example — for “underground” foreign militants who would do the “core job of killing soldiers and policemen”, today’s Kashmiri militant, they say, is mostly “underground” and would rather do the killing himself.

Since last month, the new militants on the block have also adopted a recruitment ploy not seen in the Valley before. Unlike the militant of old who would never reveal his face in public, today’s young Kashmiri militant is brazenly releasing his pictures and videos on social media — dressed in fatigues, walking about dense forests, toting a gun, cracking jokes and smiling broadly.

A senior anti-insurgency police officer calls this “an attempt to glamourise militancy and attract more youth in the manner that ISIS does”, though the Hizbul has a stated position against ISIS. “The number of militants may have increased, but there is little real militancy on the ground, so they are trying to make their presence felt in the virtual world,” he says.

Karimabad village is a stronghold of the Syed Ali Shah Geelani-led Jamaat-e-Islami.

Karimabad village is a stronghold of the Syed Ali Shah Geelani-led Jamaat-e-Islami.

Social media, says Pulwama Superintendent of Police Tejinder Singh, is being used as a retention tool as well. “Some militants who may have been wanting to quit are no longer doing so because of the glorification the social media offers.”

The most widely shared picture is of a group of 11 young militants posing in a forest, uploaded on July 1 on Facebook. All in camouflage and holding Kalashnikov rifles, the young men are relaxed as they look into the camera. The police have identified all except one who is wearing a mask.

Burhan Muzaffar Wani sits right in the middle in this group of 11. The position he occupies is strategic, not just in the picture but also in their ranks. On the run for the past five years, the 21-year-old allegedly heads the new group of militants and carries a bounty of Rs 10 lakh on his head. The police call him a “hardcore militant” who has recruited at least 80 youths in the last two years, and say he is spearheading the social media campaign.

Most young militants belong to wealthy, educated families who own big homes, such as this one in Noorpura village, Tral, from where Zakir Rashid Bhat is missing

Most young militants belong to wealthy, educated families who own big homes, such as this one in Noorpura village, Tral, from where Zakir Rashid Bhat is missing

Burhan’s story began on a summer evening in 2010, when he, his brother Khalid and a friend were riding a motorbike, and were stopped by the men of the Special Operations Group (SOG) of the J&K Police.

The friend, who does not want to named, says, “Burhan’s brother Khalid loved his red-and-white Yamaha FZ bike. Every day, he would ride up and down the steep roads of Tral. It was on one such trip that the police stopped us and asked us to fetch cigarettes. When Khalid returned with cigarettes and we started to leave, the policemen and the paramilitary forces pounced on us. Khalid fell unconscious while Burhan and I escaped. At a safe distance from the policemen, Burhan shouted, ‘I will avenge this’.”

Six months later, Burhan, then a 15-year-old Class X student, left his home and joined Hizbul Mujahideen militants who operated in Tral, a cluster of 114 villages surrounded by high mountains and dense forests. It is in these forests that Burhan and his comrades took shelter. Over the past few months, the Army has established its camps in several forests, forcing the militants to move towards the villages and the town.

Burhan belongs to a wealthy, educated family of Tral. His father Muzaffar Ahmad Wani is a school principal, his mother Maimoona Muzaffar is a science postgraduate and teaches the Quran, his brother Khalid, who was killed allegedly by the Army in April this year when he went to meet Burhan in the forests, was a postgraduate in commerce, and his two other siblings go to school.

It’s a profile that’s common to most young local militants. Burhan, it is believed, recruits youths like him — educated, tech-savvy and wealthy.

Like Zakir Rashid Bhat, who too would drive around the mountains of Tral on his Yamaha R15 bike. For the past two years, the bike has been gathering dust outside his double-storey palatial house in Noorpora village of Tral.

Burhan Muzaffar Wani, 21, is the commander of the group of new militants. A “hardcore militant” who carries a bounty of Rs 10 lakh on his head, Burhan has also spearheaded the social media campaign of the young militants.

Burhan Muzaffar Wani, 21, is the commander of the group of new militants. A “hardcore militant” who carries a bounty of Rs 10 lakh on his head, Burhan has also spearheaded the social media campaign of the young militants.

Zakir has not been home since July 17, 2013. A civil engineering student at a Chandigarh college, he was home on vacation. That day, he walked out, leaving behind a letter for his father Abdul Rashid Bhat, an engineer employed with the government. “It was a brief letter that talked about the injustice being done to Kashmiri Muslims. He had written about Kashmiri students suffering outside the Valley and felt that jihad was the only solution. I understood where he was headed,” says Bhat. The father, whose other son is a doctor and daughter a bank executive, says that the Zakir who left wasn’t the child who, until then, had “everything he wanted”. Or had excelled at carrom and participated in two national junior-level tournaments.

“He was a spendthrift. Everyday, he would take Rs 200 for ice cream and chocolates. He wanted to set up his own construction company,” Bhat says.

Last December, Zakir paid a surprise visit home when his grandfather passed away. Once clean-shaven, he now sported a beard and wore combat uniform. “He came, wept for a few minutes and left. Immediately after, an Army officer arrived looking for him. When I told him that Zakir had come and wept for a few minutes, he said, ‘He is a tiger, why would he weep?’.”

Police trace this new trend back to 2010. That year, as young boys in Kashmir had pelted stones at the Army, expressing rage over an alleged fake encounter that had killed three young men, the Army had responded with bullets, killing over 110 youths. Since then, says a Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), “the first signs of local boys joining the militant ranks began showing up”.

“Many friends or relatives of a protester killed in 2010 developed close ties with militants or joined their ranks. Several boys who were picked up or charged with stone-pelting those days later took to the gun,” he says.

Altaf Khan, the SP of Shopian in south Kashmir, says there is a need to understand the radicalisation of youth “due to underlying factors”.

Before 2010, the authorities believed they had turned the corner. Between 1996 and up to the early 2000s, many Kashmiris who had joined the militant groups had called it quits and set up Ikhwan, a counter-insurgency group that worked with the police and Army. With the Hizbul Mujahideen weakened, Pakistani terror group Lashkar-e-Toiba had arrived on the scene and taken centrestage.

At a recent Idea Exchange at The Sunday Express, A S Dulat, former R&AW chief and the Kashmir point-man during the Vajpayee administration in the early 1990s, expressed concern over “Kashmir returning to the pre-’96 era”. “A lot of these boys (who become militants) are from fairly good families, middle class, upper middle class, qualified engineers. So why are they getting into this? That’s the scary part. I’m not worried about the waving of Pakistani flags, they can be stopped any time. If ISIS flags are raised or ISIS graffiti appears in downtown Srinagar, then somebody needs to look into it,” he said.

Something else has changed: this latest phase of militancy has its base in south Kashmir.

Until now, north Kashmir had been the traditional base of militants in the Valley. Of the 33 youths who joined militancy in the first six months of this year, 30 were from the south, three from the north, and none from the central part. While the total number of militants is still the largest in the north — 69 — only 25 of them are local youths and the rest foreigners. The south, which has 60 militants, has no foreign and only local presence (see table).

The north-to-south shift also tells the story of homegrown militancy. Earlier, north was the base because the two major infiltrating frontiers for Pakistani militants, Kupwara and Handwara, are in the north. The local militants need not go that far, and have set up base in south Kashmir, especially in Pulwama, Shopian and Kulgam districts. Tral, a town in Pulwama and a stronghold of Hizbul Mujahideen, has emerged as a major base of the new militants.

Karimabad, a small village in Pulwama, is 33 km from Tral town. In March, it hit the headlines when a policeman from the village joined the Hizbul Mujahideen. Naseer Ahmad Pandit, 29, was a constable with the J&K Police’s armed battalion and was posted in Srinagar as a personal security officer with PWD minister Altaf Bukhari. On March 28, Naseer escaped from Bukhari’s residence along with two rifles. Three other boys from the village went missing the same day and joined militants.

“Naseer was perturbed by the increase in drug addiction and the police turning a blind eye to drug peddlers. One day, his colleagues beat him at the police station. I later learnt that he told his colleagues that he wouldn’t be with the police for too long,” says Pandit’s father Ghulam Rasool Pandit, a businessman.

On March 28, Naseer handed Rs 10,000 to his mother and left for duty, never to return. A graffiti outside Naseer’s house reads: “(Syed Ali Shah) Geelani is our leader”. A neighbour says it was scribbled by one Aafaq Ahmad Bhat, 25. A friend of Naseer’s, Aafaq, a postgraduate in Urdu, is believed to have joined him to become a part of the Burhan-led Hizbul Mujahideen group.

Aafaq’s house is large and concrete. A white Santro car outside has ‘Aafaq’ written on its windshield. His father, Abdul Rashid Bhat, an assistant sub-inspector with the police, and his mother, Shameema Begum, a homemaker, say, “Aafaq just left home without telling us anything.”

‘Newton’ Ishaq doesn’t figure in the photograph of 11. The police asked his brother Nisar to identify if the lone masked gunman in the photo was Newton. He wasn’t. Nor does he appear in any of the other photos or videos floating on the Internet.

“We look up the Internet every day in the hope of finding Ishaq,” Nisar says. “Maybe that might give my parents a sense of closure.”

Apr 22: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05