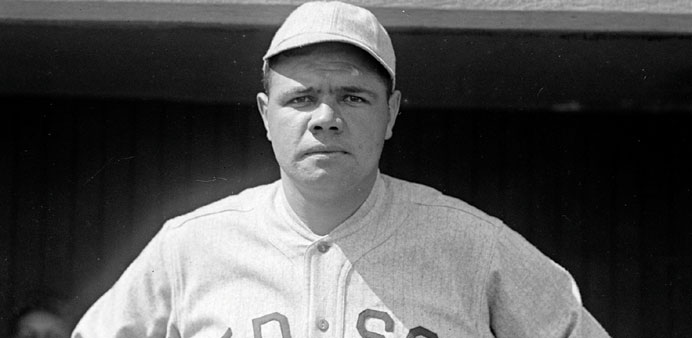

Legend: Babe Ruth

By Philip Hersh/Chicago Tribune

It was an odd year for a celebration.

The United States had plunged headlong from the Roaring Twenties into the Great Depression. In early 1933, about 25 percent of the labor force was out of work, and food lines were widespread.

Yet Chicago went ahead with the world’s fair to mark the city’s centennial, ironically called “The Century of Progress” at a moment when the nation seemed to be backsliding into Dickensian poverty.

Among the fair’s attractions was this novelty: a baseball exhibition All-Star Game, the creation of Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, whose fertile promotional mind would later bring forth football’s College All Star Game and boxing’s Golden Gloves.

The game was planned as a one-off event, a morale booster at a difficult time. Ward decided fans should select the starting nines on the 18-player teams (the managers picked the rest), and newspapers around the country distributed ballots.

The Tribune, drawing on the theme of the world’s fair, called it the “Game of the Century.” It would later become known as baseball’s “Midsummer Classic.”

But the first, played Thursday, July 6, 1933, at Comiskey Park, might as well be called the Hall of Fame Game.

Sixteen of the 30 men who played in the American League’s 4-2 win would eventually be enshrined in Cooperstown, NY So would four others who did not get into the game.

Among them were the Yankees’ Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, on anyone’s list of the 10 greatest players ever.

The managers, Connie Mack of the American League and John McGraw, who came out of his 1932 retirement to skipper the National League, are not only Hall of Famers, but also two of the game’s legendary figures. Of the 10 umpires in the Hall of Fame, two were on the field that day: Bill Klem and Bill McGowan.

Two radio networks (CBS and NBC) broadcast the game. A sellout crowd of 49,000 (according to the Tribune) or 47,595 (baseball-reference.com) watched it. The net gate receipts, $45,000, went to a charity for disabled or needy players.

And, fittingly, Ruth was the game’s star, ensuring its success and perpetuation.

In 1933, the 38-year-old was in the next-to-last full season of his career. Ruth’s prodigious and unprecedented slugging had made him the largest of the larger-than-life athletes of the ‘20s, a decade called “The Golden Age of Sports.” He took baseball from its dead-ball era to essentially the type of game current fans see.

It was Ruth’s third-inning homer, with Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer on base, that became the winning run. The Tribune play-by-play described it as a line drive that landed about 15 rows up in the right-field pavilion.

Who else but the Sultan of Swat to have hit the first home run in All Star Game history?

Surprisingly, the increasingly rotund Ruth also was a defensive star, making what the Tribune called “the most thrilling catch of the day ... in the eighth, when, running backward, he backed up against the scoreboard in right center to pull down (Hall of Famer Chick) Hafey’s great drive. If Babe had been forced back another step, he probably would have knocked himself down.”

After Ruth’s home run made it 3-0 and Gehrig walked, the Cubs’ Lon Warneke relieved NL starter Bill Hallahan of the Cardinals. Warneke pitched four innings, allowing six hits and a run.

He was among three Cubs in the game, joining shortstop Woody English and Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett. The White Sox had two: third baseman Jimmy Dykes and Hall of Fame outfielder Al Simmons.

Two months after the first MLB All Star Game, on Sept. 10, 1933, the Negro Leagues had their inaugural East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park. It also had fan voting and featured some of the greatest players in baseball history, including Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Mule Suttles and several other Hall of Famers.