- India

- International

The green mile

Be it an exaggerated dinosaur bridge in an apartment block, a brick cone that opens itself to the skies in Drum House or undulating brick walls in Devi Art Foundation. Their self-published book, Forest for the Trees; Trees for the Forest, documents projects by the firm.

Prabhakar B Bhagwat turned a basalt quarry in Timba, Gujarat, into a self-sustaining forest. His father Bhalchandra V Bhagwat developed the Empress Botanical Gardens, Pune, as its Superintendent. His son, Aniket Bhagwat carries forward the legacy, plating up landscapes with fractals and contrasting geometries. With projects spread across the country, Aniket’s Nolan-esque designs confront history and theatre all at once. From corporate gardens to farm-inspired homes, from schools to hotels, from universities to master planning, for over four decades M/s Prabhakar B Bhagwat has been building spaces where architectural features become observers and protagonists.

Be it an exaggerated dinosaur bridge in an apartment block, a brick cone that opens itself to the skies in Drum House or undulating brick walls in Devi Art Foundation. Their self-published book, Forest for the Trees; Trees for the Forest, documents projects by the firm, but it also shows how clients became friends, seeds grew into farms, and symbols told stories. These eventually form characters in a masque where their exits and entries are as important as the silences in between. Excerpts from an interview with Aniket:

Timba: Hard mass of rock in a basalt quarry was turned into a wetland with pedestrian trails, planting and ponds

Timba: Hard mass of rock in a basalt quarry was turned into a wetland with pedestrian trails, planting and ponds

Timba

Timba

The Timba quarry project done by your father in 1985 seems like it has always been like that. Your landscape designs appear more deliberate and planned. How do you think landscapes should be designed? Forced or serendipitous?

These are different landscapes. We tend to use the word “landscapes” as if it means only one thing; but of course it’s not. Timba for example was the restoration of a 200-acre, exhausted basalt quarry. It was a slow and carefully done ecological reconstruction; it’s really about allowing nature to re-establish itself. It started with improving the soil, then allowing grasses that could shelter and shade the small trees, diverting a nearby seasonal stream to fill the quarry, and then stocking the water with fish, and affording the place protection so that nature slowly regained its hold. Along with it, forests bloomed and birds nested. Even today there are very few examples like it in the world. On the other hand if you take, say the landscapes of Devigadh which is an old medieval fort near Udaipur, they can’t take the same route. The fort built along a hill, had many courts rising from the lower ground. There was nothing in the courts but the names ‘darbar’ or ‘zenana’. The landscapes for these were really mental constructs, that resurrected the narratives of this palace. In abstract ways, the landscape design referred to the way water was traditionally revered in lands that had little of it and paid obeisance to the beautiful water rills of Mandu near Indore. It celebrated the idea of a darbar by a rough hewn stone throne that presided over the cosmos with a orb etched in the stone floor while the zenana translated as a fountain that spews water inside, almost to reflect the manner in which women tend so tragically to internalise their emotions in feudal lands. It made cultural and social connections. So, landscapes should be planned, like life is planned, never this or that, but what they want to be.

Blossom: An abandoned factory hosts choreographed landscaped elements such as sculpted earth mounds that lead to mango groves.

Blossom: An abandoned factory hosts choreographed landscaped elements such as sculpted earth mounds that lead to mango groves.

Blossom

Blossom

Between 1995 and 2005 your firm seemed to have developed its own vocabulary. How has the firm, which has seen three generations of landscape architects, grown over the years?

Every summer I would go to Pune for holidays. My grandfather had long retired. But I remember going to the Saakal office near Shanwar Wada once a week, where he held a workshop for readers who had questions on how to grow vegetables, flowers and other plants. He had such patience and he cared enough to keep on explaining things till he was sure that people knew what to do.

And then when I started studying architecture, I would often ride pillion with my father on his old white Lambretta scooter and go to sites at the crack of dawn where he would plant gardens. It really was theatre, the way he selected plants from a large truck load, and tapped a stick on the ground where he wanted a particular plant placed and a large group of workers would follow him and he would pace up and down for hours at an incredible speed. I would enjoy seeing this over and over.

From 1970s after my father formally set up his design firm, he did these very lyrical and gentle landscapes that really told the story of trees. Many of them are no more; and it struck me how fragile these landscapes really were. Sadly, we have no photographic records either, though we have drawings. The work from the late ’90s has been recorded. I think a lot of the work we do, comes from the hurt of seeing the earlier work vanish, so we tend to embed something into the landscape that will make its reading more robust.

The landscapes my grandfather and father did had a vocabulary albeit a different one, and hopefully there is one now.

Seeing the way they worked, or dealt with trees and the land, one learnt about observing nature carefully, about seeing order in them that are not apparent. Slowly the idea of landscapes in its fullest entirety seems to have seeped into our bones, and so for us that I think is the biggest growth. That we can imagine ways of thinking about landscape that is dynamic, thoughtful, abstract and communicative, irrespective of scale or type of project.

But the biggest growth was the learning of a spirit, a way of looking at life that was full of conviction and passion.

Half Way Retreat: The landscape uses patterns from agriculture while its water channels criss-cross the site. Far from any sense of continuity, the design celebrates fractals.

Half Way Retreat: The landscape uses patterns from agriculture while its water channels criss-cross the site. Far from any sense of continuity, the design celebrates fractals.

Half way retreat

Half way retreat

In your book Forest for the Trees, Tress for the Forest you say that “one is a product of the life we live each day”. How do your everyday experiences inform your design process?

We live in a country of such vibrancy and complexity and just as the air that touches the body, its many nuances touches one’s soul — people, noise, broken cities, poverty, happiness, music, and cinema — all this becomes a strange concoction in my head, and the design always seems a way to negotiate this space. I like fractals, I like contradictions, I resent sameness. I find it tedious, and unreal. Life is not like that. Not unless you are a vegetable, or a saint. It soars, scares, sings and sleeps; all in one day. So I like spaces like that, which surprise and seem disconnected to the last space; not revealing the next. Also, you can’t escape history if you are an Indian, it can be a huge weight or you can wear it lightly and live with it; I choose the later.

Drum House: The space has many actors who not only dress differently but behave differently too

Drum House: The space has many actors who not only dress differently but behave differently too

Drum House

Drum House

If you see Half Way Retreat, which is a large home set in a garden, dry sits next to wet, dark next to light, free next to constrained and they are almost notionally, yet powerfully separated. In the Drum House, which is really about many strange characters, the drum, the stockade, the concourse, wrapped in elegant concrete, there is no seeming thread that ties them together and yet there is a subliminal beat that does. The Gala housing landscape has a huge whimsical 100-feet-long ‘dinosaur’, its bold expression was a rejection of the loss of identity in our cities. The lower grounds of the Bridge House, which recreated many crop patterns was about the loss of agriculture, and its lyrical order, and the play spaces in Shirpur is a tribute to poster art in our cities, and how dead walls can be such potent tools of communication.

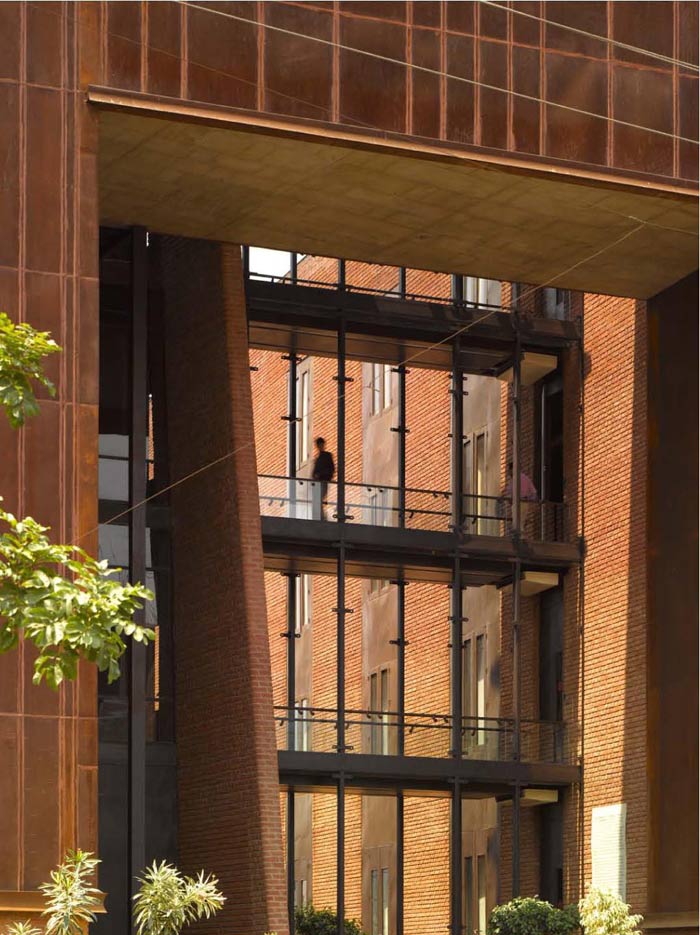

Devi Art Foundation: With Corten steel skin and custom-made exposed bricks that twist and turn, the Devi Art Foundation building design testifies to the avant-garde art it hosts

Devi Art Foundation: With Corten steel skin and custom-made exposed bricks that twist and turn, the Devi Art Foundation building design testifies to the avant-garde art it hosts

Devi Art Foundation

Devi Art Foundation

Craft and theatre often walk hand-in-hand in your architectural projects. They lend themselves to exaggeration but also become observers of the landscape and environment.

Look at us, we are the biggest dramabaaz, nautankis in the world. Also, there are very few lands left in the world where the hand and the mind come together so beautifully be it in metal, or stone, or cloth, or pigments. The idea of craft and that too without a fuss, in humble places of production is something we see all the time around us. It’s natural then to use this as a resource, as an idea in the work we do. For example, in the Devi Art Foundation building and then yet again at the Alchemist’s Abode in Baroda we took what were conventional office buildings and designed them to efficiencies that are the norm, with budgets that are not much higher than the market, to craft large projects with the precision of the hand. I somehow reject the idea of the industrial in the way we have now made it commonplace. I do understand that with the scales we have to build in this country, that is one way to go. Most beautiful cities in the world, or that which we consider of value even today used tools of mass production that were available then, with the clear control of the mind and the hand. I miss that in a lot of the new faceless work, and hence perhaps root for it so strongly in ours.

Bridge House: The house on two hills is connected by a bridge, textured with installations, storm water trenches and wild forest planting

Bridge House: The house on two hills is connected by a bridge, textured with installations, storm water trenches and wild forest planting

Bridge House

Bridge House

Why is the profession of interior design special, as you say in your book? Most people mistake it for interior decoration

I believe that the profession of interior design is special – it’s the one that comes closest to the human body; and touches it sensorially and literally. To me, it’s an art and equally spatial design, that surrounds the human body in a tight wrap, and can be realised rather quickly (as compared to say landscape design or architecture) and can have a life of one’s choosing (again something you can’t do in architecture and landscape); so to say, it can be temporal or done for posterity. What could be more fascinating than that? It does not suffer the vagrancies of development permissions, nor gets washed away or shrivel because of the climate (as do landscape and architecture); and what could be more secure than that? So really to me it’s a liberating form of design, one that tests the mind at many levels, and scales of attention simultaneously; I do believe if taken seriously it can be seen at such poetic and philosophical heights, that would leave us moved each day.

Akash: This 9,000 sqm wedding venue lit up with over 3,000 lights enclosed in cloud-shaped holders create an ethereal magical effect

Akash: This 9,000 sqm wedding venue lit up with over 3,000 lights enclosed in cloud-shaped holders create an ethereal magical effect

You pioneered 12 on 12, a forum where architects presented 12 slides for 12 minutes to a design audience, and have co-authored Spade, a four-volume magazine with architect Samira Rathod that deliberated design in the country. Do you think we lack dialogue on architecture and design in India and that’s why we still haven’t made a mark on the international scene?

Absolutely. I find that as a community we are not interested in things beyond the daily, or things pertaining to self. We don’t want to invest time in subjects that seem peripheral or esoteric; and we surely don’t want to invest time to evaluating ourselves. Things are changing, but not enough. Many initiatives have begun, where designers are talking to each other. We need to create robust platforms to discuss, evaluate and introspect else we will keep working in isolation, and that can never be good for any profession. But that’s only one set of reasons. There are others. Such as lack of patronage and faith in Indian architects, or even the desire of architects to push the limits and go beyond themselves.

Gala Haven: The lack of emotions in cookie-cutter apartments have led to a whimsical garden with large trellis structures, caves for children, a giant dinosaur bridge and many play areas

Gala Haven: The lack of emotions in cookie-cutter apartments have led to a whimsical garden with large trellis structures, caves for children, a giant dinosaur bridge and many play areas

Gala Haven

Gala Haven

What’s on your drawing boards currently?

We are 40 odd people and work like we are possessed. We have a host of homes, office buildings, small institutional buildings, large master plans, and landscapes of all shapes and sizes, and over time we have been careful to take on work that we think we can bring value to. Right now, many of us are continuously working on the master plan, urban design and landscape design for a new city that has already started construction. It will be spread over 4,000 acres and will be home to over two million people. Then in the mill area of Mumbai is a public park that narrates the loss of the textile mills and also directs attention to some of Mumbai’s beautiful landscape vignettes, like the Borivili National Park, or tells the story of how the seven islands became Mumbai. Then there is a wonderful home that sits in a large orchard, built in really beautifully crafted brick that we have been honing for a year now, and of course an office building in Baroda under construction really is art and inspired by Paul Klee’s 1929 painting Uncomposed Objects in Space.

In which buildings in India do you think architecture, interior design and landscape come together?

The Golconde Ashram in Pondicherry really has to take that prize. Built in 1942, under the direct supervision of the Mother, it was designed by Antonin Raymond as a dormitory for the disciples of Sri Aurobindo. It’s got exquisite furniture by George Nakashima, and the gardens, which have a slightly oriental flavour to it, sit as a third actor and are equally meditative. I think every lover of design in India must see it and students must spend months absorbing it. Having said that of course there are many a modern projects, especially homes. I used to actually love the work that Achyut Kanvinde did and where my father did the gardens, and I thought it had a quality of Frank Llyod Wright’s sense of attention to detail. Those homes in Ahmedabad done in the ’60s were rather beautiful.

Forest for the Trees; Trees for the Forest is available for Rs 1,950 (exclusive of courier charges). Mail: landscapeindia@usa.net or call 079- 26923054

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05