Yeh chirag bujh rahe hain

Mere saath jalte jalte... (Pakeezah)

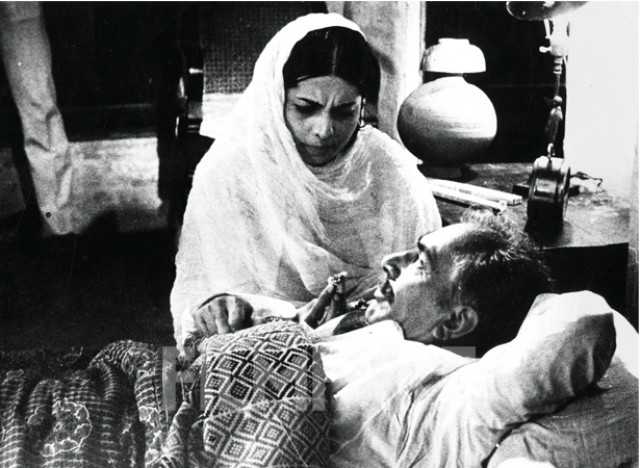

The lament in bejewelled Meena Kumari’s eyes, the opulence of Kamal Amrohi’s framework, the insanity of Ghulam Mohammed’s tabla... all this could not have achieved its moment of cinematic symphony had it not been for Kaifi Azmi’s poetry.

Because Kaifi was poetry. He may have been a man of many moods – crusader, radical, nationalist, socialist, agnostic... romantic. But he expressed these affiliations through the prism of poetry. The tyranny of time – Waqt ne kiya kya haseen situm, the charade of relationships – Woh jo apna tha wohi kisi aur ka kyun hai, heroism – Zinda rehne ke mausam bahut hai magar, jaan dene ki rut aati nahin, feminism - Jannat ek aur hai jo mard ke pahlu mein nahin (poem Aurat)... Kaifi chose to translate the prosaic in lyrical metaphors. What lent his lyrics the exquisiteness of filigree was the liberal use of Urdu and a sensibility, passionate as a man’s and fragile as a woman’s. As daughter Shabana Azmi explained this creative dichotomy, “In Abba, the yin and the yang co-existed.” Truly, what can be more sensual than Ek raat hoke nidar, mujhe jeene do? And yet more mystical than Tu hi sagar tu hi kinara?

Kaifi was a lover who understood life in all its changing colours – yet could not break away from its spell. That’s why, perhaps, his work is timeless, as enduring as life itself. Contemporary poet/lyricist Irshad Kamil, of Jab We Met, Rockstar, Love Aaj Kal and Highway fame, pays a tribute to the legendary writer saying, “Those songs stay alive, which don’t belong to just the film. Their reach is beyond time and generations. Kaifi saab’s lyrics had that everlasting quality. That’s why they have filtered through the sieve of time.” Read on for more...

My growing years were spent in Malerkotla (Punjab), a place which has retained the flavour of pre-Partition Lahore. It’s steeped in Urdu poetry, music and tehzeeb (culture). I was around 15 and had just entered college, when one day we were told that Abshar, a forum to promote Urdu culture, was holding an All India Mushaira (a gathering of poets) at the club. We students were asked to look after the great shayars including Kaifi Azmi, Nida Fazli, Bashir Badr... present there.

We went to the guest house where the poets were put up. The poets were relaxing in the hall as the mushaira was to be held at night. Kaifi saab asked for water, which I rushed to give. “Kya naam hai tumhara?” he asked. I replied, “Irshad (‘irshad’ is said when you ask a poet to recite his couplet)!” Kaifi saab said, “Bada shayrana naam hai (what a poetic name)!” Later, he looked at his kurta and remarked that it was creased. When I offered to iron it for him, he smiled and said, “People don’t see the wrinkles on my kurta but come to hear my poetry.” That was my brief and only meeting with Kaifi saab. But his influence on me through my journey as a poet continued.

Those days, All India Radio aired a programme where nazms and ghazals of noted poets were played. A lot of Kaifi saab’s ghazals were played, some of which were sung by Begum Akhtar, Rajendra and Nina Mehta and others.

I started understanding his lyrics, the ‘kaifiyat’ (state of mind) behind them. My interest in the creative process grew. Like he often said, “Junoon main hi sukoon hai (only in passion can one find peace).” His poetry is deeply visual. It conjures up rich images. And what you can visualise, you can remember. He could create a painting with words. Today we have diluted the purity of the language. Earlier lyricists came from a literary background. The producers and directors understood poetry. But today the producer, the director, the lyricist and the music director, each one tries to dictate his terms when none has any knowledge of the language. All that they want is a hit irrespective of the quality. Kaifi saab preserved the purity of the language rather than playing with it. He came in when there were legendary lyricists around. But he joined their league because of his earthy writing. If there was a hint of folk in Shailendra’s verses, then Sahir Ludhianvi’s works were steeped in romantic philosophy and Shakeel Badayuni’s verses had imprints of academic perfection… but Kaifi saab remained the poet of the common man. It’s difficult to comment on the work of a poet of his stature… but here are a few favourites...

KAGAZ KE PHOOL (1959)

Music: D Burman

The song Waqt ne kiya from Kagaz Ke Phool, which talks about the onslaught of time, has turned timeless. In blaming time for the souring of relationships, you find solace. Another gem is Dekhi zamane ki yaari, bicchde sabhi baari baari, which speaks of the fickleness of life.

KOHRA (1964)

Music: Hemant Kumar

I first heard the Hemant Kumar sung Yeh nayan dare dare on radio while in college. Those days every young man wanted to sing it for his beloved. O beqaraar dil was based on Hemant Kumar’s earlier recorded Bengali composition O nodi re (film Siddarth). If one listens to O nodi re and O beqarar dil back to back then you understand the contribution of the lyricist. In the Bengali version the words are not sad but seem sad. In the Hindi version, the words are sad but the song does not seem so because of the master touch of Kaifi saab. Mujhe tu khushi na de, nayi zindagi na de is expressive of the stage of love when pain has become pleasure. This thought gives the hint of tasawwuf or mystical love.

HAQEEQAT (1964)

music: Madan Mohan

Kaifi saab’s collaboration with Madan Mohan was one of the finest. Main yeh sochkar elicits a hope for reconciliation with the phrase Hawaon mein lehrata ata tha daman creating a heartbreaking visual. Those who believe that lyric writing is only about rhymes can learn from this song. The music is minimal yet evocative. So is Hoke majboor mujhe ussne bhulaya hoga with realistic details like bandh kamre mein jo khat mere jalaaye honge… Also, Ab tumhare hawale watan is the finest patriotic number, which reveals Kaifi saab’s nationalist leanings.

HEER RAANJHA (1970)

music: Madan Mohan

The film was based on the Punjabi epic poem Heer written by Waris Shah (1766). To match that Kaifi saab wrote the dialogue of the film in verse form. Ye duniya ye mehfil is a great piece, particularly the lines, ‘Unko khuda mile hai khuda ki jinhein talash...’. These lines not only go perfectly with the character of Raanjha but also express Kaifi saab’s communist ideology. I wonder if I was inspired by this very taqraar (acrimony) with the Creator when I wrote Kaisa khuda hai tu in Ajj din chadheya (Love Aaj Aur Kal). Also, the song is well- filmed against landscapes and changing seasons. The journey to the light-hearted Milo na tum toh is interesting. When Raanjha doesn’t turn up at the mela, Heer reaches his cottage looking for him… and the song unfolds.

HANSTE ZAKHM (1973)

music: Madan Mohan

The ghazal Aaj socha toh aansoo is so ironical. The poet desires happiness but ends up in tears at the thought of not having smiled since long. The matla (first two lines) is drenched in emotion. As also the lines, Dil ki nazuk ragein tootti hai yaad itna bhi koi na aaye… There’s a nazakat (delicateness) in the ghazal Betaab dil ki tamanna yahi hai, which speaks of eternal love.

GARM HAWA (1975)

music: Bahadur Khan

A true lyricist is neither male nor female, neither an atheist, nor a priest. When he writes, he tries to justify the character of the film. ‘Tumse nahin hai koi parda... Maula Salim Chishti, this Sufiana qawwali in the film proves my point. Kaifi saab was known to be an atheist. But after listening to this qawwali you question that. By not going to a place of worship, you don’t become unreligious. Going there doesn’t make you religious either. Also, you only tend to deny the existence of something, whose presence you feel somewhere. Yun hi koi mil gaya tha sare raah chalte chalte from Pakeezah (1972) also has such layers. While it seems to be about romantic love, it ventures into the territory of Sufism. It could apply to a bond between a peer (guru) and murshid (disciple) and their meeting along the way.

ARTH (1983)

music: Jagjit Singh

Koi yeh kaise bataye ke woh tanha kyon hai... this one line is so pregnant with meaning. It makes you dwell on the innocence and helplessness of the heart. How one can explain why one is alone? There may be hundred reasons, valid or invalid. And yet there will remain so much, which can never be explained.

Also, in Tum itna jo muskura rahe ho… (Shabana Azmi trying to hide her tears on learning about her divorce) the mastery lies in Kaifi saab’s words. The picturisation is merely aided by the imagery. Who can but not be affected by the lines Jin zakhmon ko waqt bhar chala hai, tum kyon unhe chhede jaa rahe ho?

TAMANNA (1997)

music: Anu Malik

Kaifi saab’s poem Aurat with the famous lines Uth meri jaan… mere saath hi chalna hai tujhe was written in the early ’50s, supposedly for wife Shaukatji (Azmi). But at a wider level it expresses Kaifi saab’s progressive thought. The mood during Independence was that of sidelining love for the national cause. But Kaifi saab’s Aurat urged the woman to walk along with the man. Ghar ki ladai ho ya mulk ki – his was a contemporary take on the woman. The same poem was sung by Sonu Nigam in Mahesh Bhatt’s Tamanna. My Phataka guddi (Highway) has the similar sentiment of revering the strength of a woman.

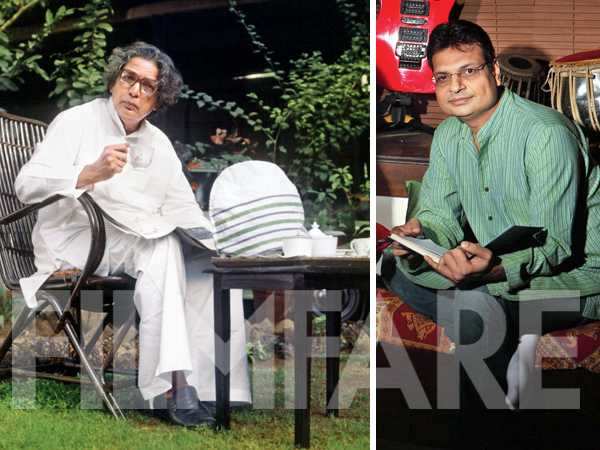

ABOUT KAIFI AZMI

Kaifi Azmi’s real name was Akhtar Husain Rizvi.

Born in a zamindar family in Mijwan, Azamgarh, Kaifi wrote his first ghazal Itna toh zindagi mein kisi ki khalal pade at the age of 11, which was later rendered by Begum Akhtar.

At 19, he joined the Communist Party and started writing for the party’s paper Quami Jung and moved to Bombay.

He wrote his first lyric for Shahid Lateef’s Buzdil 1952.

His noted songs include Jaane kya dhoondhti rehti hai yeh aankhen and Jeet hi lenge baazi hum tum from Shola Aur Shabnam (1961).

One of Suraiya’s last recorded number Dhadakte dil ki tammana (Shama, 1961) was written by Kaifi.

His lyrics in Anupama (1966), Lata Mangeshkar’s Kuch dil ne kaha and Hemant Kumar’s Ya dil ki suno are considered classics.

For Naunihal (1967), he wrote the song Meri awaz suno, which was played in the documentary on late Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru’s funeral.

Kaifi was the All India President of the Indian People Theatre Association (IPTA) and an active member of the Progressive Writers Association (PWA).

He wrote the dialogue for Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1976).

The Kanu Roy-composed song Aaj ki kali ghata, in Uski Kahani (1967) sung by Geeta Dutt, evoked rich imagery with minimal orchestration.

Manna Dey’s Tum bin jeevan in Bawarchi (1971) based on raag Bhinn shadajj, shows his mastery over Hindi.

Tu hi saagar hai tu hi kinara won Sulakshana Pandit the Filmfare Best Female Playback Award He played a role in Saeed Mirza’s Naseem (1995).

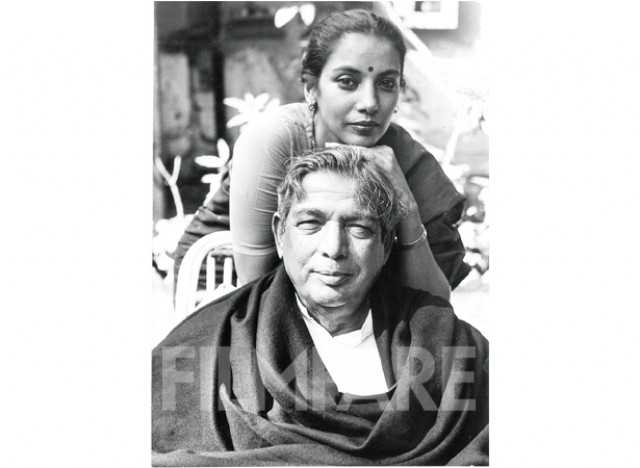

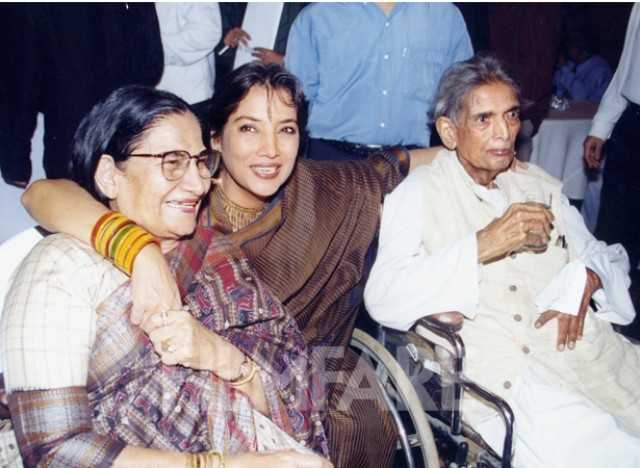

After he suffered a paralytic stroke, he settled in Mijwan and set up the NGO, Mijwan Welfare Society, for the empowerment of women, now run by daughter/actor Shabana Azmi.

He passed away on May 10, 2002 at 83.

KAIFI AZMI’S FILMFARE AWARDS

Best Dialogue - Garm Hawa (1975)

Best Screenplay - (with Shama Zaidi) Garm Hawa (1975)

Best Story (with Ismat Chughtai) Garm Hawa (1975)

SHOW COMMENTS