This post originally appeared in Caixin, and is a part of the ongoing project Touching Home in China, which follows adopted American teenagers who return to their birth country to learn from girls their age about what it’s like to grow up female in 21st-century China.

Early in September 1996, two girls were born eight days apart in China’s eastern province of Jiangsu. Each daughter was abandoned a day or so after her birth in a rural town about 25 kilometers from the city of Changzhou. On Sept. 3, the first of these two girls was found in Xixiashu Town. Those who found her said she was 1 day old. Then, 10 days later, the other girl baby was found in Xiaxi Town. Three days old, those who found her estimated. But neither the date nor location of the two girls’ births, nor the identity of their parents, is known, since it was strangers who found them after the babies had been left on their own.

Each of these girls has celebrated 17 birthdays in America, on the date that these strangers in China estimated that she was born. For good luck, the girls blow out the candles on their birthday cakes, hoping to extinguish them all in one breath as family and friends sing “Happy Birthday.” On such occasions, and others, thoughts of how their lives began in China light up inside them.

An American family adopted each girl when she was 9 months old. Yet their journeys to new families and a new country actually began on the day each girl was found.

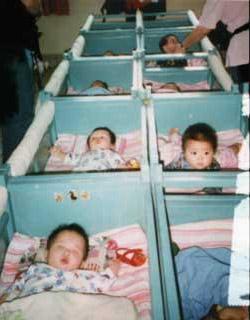

That was because local police drove each girl to the Children’s Welfare Institute in Changzhou, an orphanage where foreigners come to adopt children, where each was put into a crib in a second-floor nursery with more than 100 babies. Their wood-paneled beds touched in closely stacked rows. In some cribs two babies shared space normally home to one. Nearly all of these babies were healthy girls. If a boy was among them, his disability was likely visible.

Each girl came into the orphanage due to the procreative pressures that China’s one-child policy exerted on couples. Locally enforced family-planning rules determined how many children each couple could have. When a couple exceeded its prescribed limit, punishment would usually follow—a painfully high “social maintenance fee” was demanded of the family, or a member of the family lost a job, or an over-quota child was removed from this family’s home. It was up to local family-planning cadres to decide.

In many of China’s provinces, a couple with a rural household registration, known as a hukou, could have a second child if its first had been a daughter. In Jiangsu, no such distinction exists for rural and city families; one child is every family’s limit, unless a couple qualifies for an exemption, and those are rare. Families who work the land have for centuries needed sons for manual labor, but boys are needed as much for the financial and care support they provide parents in their elder years as they are for their muscles. It is expected that a son’s wife will provide this household care. So when a daughter is born first, even if parents want to raise her, a paternal grandparent or other member of the family might pressure the couple to abandon her. Then, a grandson could be born and raised to continue the family’s patrilineal legacy. Perhaps the families of these girls from Xixiashu and Xiaxi had such conversations when each was born.

Going to America

From the moment the Xiaxi newborn was put in her orphanage crib, she and the girl from Xixiashu began their close-knit journey through childhood and into adolescence. In their first winter together, they were crib neighbors. As summer approached, two single women—I was one of them—left the United States headed for the girls’ orphanage. Our arrival in Changzhou signaled that these girls’ lives were about to change dramatically, just as their lives did nine months earlier. While they were in the orphanage, the China Center of Adoption Affairs in Beijing had matched them, as orphans, to foreign families that wanted to adopt a child. I was matched to become the adoptive mother of Chang Yulu. Judith, who was in my adoption travel group, was told her daughter would be Chang Yuchang.

Photo by Melissa Ludtke

On June 4, 1997, Yuchang and Yulu heard us call them strange sounding names as we held them for the first time. Yuchang heard “Jennie” from a woman who held her close to kiss her on her forehead. As I cradled Yulu in my lap, I called her “Maya.”

Hearing their American names was just a first step in these girls’ rapid, life-altering transitions. Along with signing two sets of adoption papers, first in Changzhou, then in Nanjing, the provincial capital, we handed the director in Changzhou the specified orphanage donation in Chinese renminbi. Soon our daughters were with us in hotel rooms as we traveled around China. Our next stop was Guangzhou, where Maya and Jennie passed their mandatory physical exams so the U.S. Consulate could issue each girl an entry visa to her new country. The girls being adopted by the six other families in our travel group—two single women and four couples—went through this same process.

I carried Maya on my back as our adoption group visited tourist sights in Beijing and climbed the Great Wall. After our plane home landed in Boston, Jennie was driven 20 miles west to her new home in the residential town of Sudbury. Maya and I went just a few miles across the Charles River before we climbed two flights of stairs to arrive at our smaller home in the city of Cambridge.

Going Home in China

When Jennie and Maya were about to enter their final year of high school, they set out to travel to the rural towns in China where each was abandoned as a baby. They were greeted by a record-setting heat wave, so on brutally humid and hot mornings, Jennie and Maya left their air-conditioned Changzhou hotel room to travel by car to Xiaxi or Xixiashu. There, they hung out, rarely in air-conditioned surroundings, with girls their age who grew up in the places that these Americans might have lived as children and teens.

Cross-cultural encounters among girls born in the same place in China but with distant and very different upbringings are rare. Perhaps it’s because arranging this girl-to-girl journey of discovery is difficult. To simply show up as Americans and declare a desire to hang out with girls in your “hometown” seems intrusive and possibly presumptuous. Such an approach seems bound to lead to unsatisfying dead ends. Instead, Jennie and Maya arrived in their towns to meet girls who grew up there only after months of thoughtful work. To do this meant relying on incredible assistance and valuable guidance from Chinese friends. Those who made this visit possible were female journalists I knew from their time in America when they were experiencing fellowships at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, where I worked.

After the Lunar New Year in 2013, I asked one friend in China, Wu Nan, if she would travel to Xixiashu and Xiaxi to meet girls in these two towns. (I paid her for her time and assistance.) I hoped she’d find two or three girls in each town who wanted to spend time getting to know Jennie and Maya. If she succeeded, then we’d make plans to travel. Back in Beijing, Nan told us about girls eager to have this experience and sent us their names and photos of them, their homes and the towns. She gave us cellphone numbers for each girl and family members’ numbers, too, for some of them. She made one request: Do not try to contact the girls until mid-June. That’s when they’d be done taking critical entrance exams for school. Results of those tests would determine the next step of each girl’s life with her school assignment. We should not distract the girls from their studies.

Nan understood the value of introducing us to a well-respected woman in each town. These women could assure others in the town about the purpose of our visit there. Neither destination was on foreigners’ travel itineraries, so it was likely these girls would be the first ones whom people there would meet. Trust would be a vital ingredient in forming relationships. In Xiaxi, Nan selected Ms. Hu, who teaches English in the middle school. If Maya had not been abandoned, Ms. Hu would have taught her the only language she now speaks fluently. Teacher Hu was raised in Xiaxi and married a man also from this farming town. On days she teaches, Ms. Hu lives with her mother-in-law near the school. Her husband, a chemist, works in a city 400 kilometers away. Their only child, Xue Piao, is a year older than Maya and Jennie. She uses the American name of Tiara. By the time the Americans arrived, Tiara was preparing to go to the United States as a first-year student at Syracuse University. She’d use “Tiara” when she arrived.

In Xixiashu, Nan met Huang Xinzhen, the local director of the All-China Women’s Federation, the government organization for women that Mao Zedong established in 1949. When Nan told her about the American girls’ upcoming visit, she was, as Nan wrote to us, “touched by the story of Jennie and Maya and would like to help us.” In August, Huang Xinzhen greeted Jennie on her first day in Xixiashu. With her was the village leader, and they guided Jennie through the ancient opera house and temple before Jennie was introduced to the local girl, Jin Shan, who’d told Nan many months before that she wanted to meet Jennie.

Being Home in China

Nan had told the Chinese girls that the American girls’ lives had begun in their town. Perhaps this is why the Chinese and American girls had such a visceral connection as soon as they met. Quickly they were interacting as friends in spite of challenges posed by communicating in different languages. The Chinese girls studied English in school, but their ability to understand what the Americans said varied considerably. Similarly, what Chinese girls could say to the Americans depended on how well each spoke English. If they needed help, I’d arranged for a translator to be with them.

Still, given their cultural divides as well, the possibility of misinterpretation and misunderstanding loomed large. In the process of translation, nuances of meaning can easily be lost. When Maya was young, then more intensively in high school, she had studied Mandarin. But she had never spoken it outside class. Nor had she ever heard Mandarin spoken as rapidly as she was hearing it in China. Added to the speed of these girls’ delivery was their rural dialect. All of this combined to strain Maya’s limited ability to comprehend and to communicate in Mandarin. Jennie did not study Mandarin since her high school didn’t offer it as a language. Instead, she studied French. Despite these challenges, the girls worked to build bridges of understanding across cultural chasms that had been carved out of their different childhood experiences.

Each girl embraced wholeheartedly her new friendships. Like teens everywhere, the girls found common ground in music, in telling each other stories about their lives, and in sharing gripes about the adults who raised them. They swapped songs on their phones, and Maya and Jennie became devoted fans of the Chinese version of American Idol, picking favorites among the contestants. The girls shopped together. They ate with each other’s families in their towns and on their own in Changzhou. They styled each other’s hair for fun and looked into the future at what their lives might be as wives and mothers.

Before going back to China, the Americans talked with Katie Naftzger, a counselor who specializes in talking with adopted teens. Katie joined her American family when she was adopted from South Korea. She’d gone “home” to learn what she could about where she was from. In preparing Jennie and Maya for their trip to China, her own experiences informed her guidance. Most of all, Katie helped the girls think about feelings that were likely to surface in Xixiashu and Xiaxi and get them ready for likely questions the girls, their families, and their neighbors would ask once they knew the Americans had once been babies in their town.

“How did you end up living in America?” everyone wanted to know. But before that, most asked each girl if she knew her Chinese mother. By the time she could respond, the questioner had offered help in finding her. Whenever this happened, each girl would try to explain in English that she knows nothing about her birth family. Given the sensitivity of this topic, a need to translate inevitably followed. Then, Maya would tell the person who asked—and it always was a female—that this is not why she’d come home. (For Jennie, this question of reconnecting with her birth family was a bit tougher to answer because she arrived open to looking for her birth family, if a search could happen as part of getting to know the girls. Along the way, it became apparent that it would not happen on this trip.) The girls had come back to hang out with “hometown” girls their age. Another time, perhaps, one or both would return to search, but not now. It comforted the Americans to learn that they had many friends to support and help them, if they decided that’s what they wanted to do.

Preparing to handle these moments emotionally was a good idea. Even with our translator’s help, it was extremely difficult to convey concepts of abandonment and adoption across cultural borders that give different meanings to these words. What Jennie and Maya hear in saying these words isn’t necessarily what girls and women in rural China understand them to mean.

In America, most people know that healthy baby girls have been abandoned in China. In all 50 of our states, it’s likely that at least one family has traveled to China to adopt a child. In newspapers and on TV and radio news shows, stories about adoption are told routinely, and in many stories, families are raising children from China. Magazines about adoption focus on birth mothers who decide to have their babies be adopted in what’s known as “open” adoptions, in which birth and adoptive parents agree to stay in touch. In schools, adoption takes center stage as a topic of classroom discussion. When Maya was 5 years old, she and I did a presentation about her adoption with her kindergarten classmates; each student had a week to share, in many ways, the story of her family. In November, Americans celebrate the ways that families are formed through adoption as part of National Adoption Month.

In being with the girls in China, Jennie and Maya discovered that adoption is not a topic they talk about openly. The Chinese girls were surprised to learn that healthy female babies were abandoned in their towns around the same time they were born. Zheng Fan, who was raised by her parents in Xixiashu after her brother died of a brain tumor, told the Americans what she knew about abandoned babies. If a couple, she said, “gives birth to a child that is disabled and they can’t see the future of the children, they will abandon them.” Another reason, Fan speculated, was that “if parents aren’t responsible or the family can’t afford to raise their children, they abandon the children.” She believes Chinese parents abandon more girls than they do boys because “in ancient times most emperors are men—only one female emperor—so people take males as more valued than females,” Fan said. “In ancient times of China, men can do many things such as fight in wars, but the girls receive less education, so the girls just stay at home.”

Reports and rumors circulate throughout China about children being kidnapped, and some are sold to other families. Adoption is not talked about in school, nor is it a topic discussed within families. It’s possible that in Xiaxi, a child whom these girls know came to her family through an informal arrangement considered to be adoption. It’s unlikely her friends would know that she was not that family’s child by birth. The girl might also not know. The Chinese girls were also astonished to learn how many foreign families are raising children who were abandoned by their Chinese birth parents. That these parents don’t look like their children, yet are raising and loving them, was a challenging notion for the Chinese girls to absorb since no one looks quite that different than anyone else in their towns.

Only in befriending Jennie and Maya, hearing how they became Americans, and meeting their American moms did the Chinese girls attain the rock-solid evidence they needed to believe that this happens.

Being with Jennie and Maya was also the first time the Chinese girls were face-to-face with a foreigner. They’d seen Americans on TV, played hit songs from America, and learned about the entertainers singing them. Chen Chen, a girl Maya’s age who was raised by her grandparents in Xiaxi, likes nothing better than blaring American songs from her cellphone and singing along on walks around town. She wants to learn “Western style of singing.” But no connection to America came close to actually being with an American girl who looks like them, has a direct connection to their town, and wants to learn everything she can about them.

Pieces of a Dual Identity

In Xixiashu and Xiaxi, Jennie and Maya fit new pieces into the puzzle of dual identity that comes with being Chinese-born and raised as a daughter in a Caucasian family in America. Being in China reconnected them to some of what has made them who they are. They found parts of themselves that in America they don’t have much opportunity to see, touch, smell, or feel. This happened when the girls got to spend day after day in places where everybody looked like they do and where each was in the place where she’d been as a baby. Sure, they’d visited Boston’s Chinatown and Maya had gone to Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York, but on those visits they’d been with family members or classmates. That wasn’t at all like mixing with girls in their hometowns.

Yet looking just like everyone around them raised new issues for the Americans. On the girls’ first outing to explore an underground mall in Changzhou, Maya tried speaking Mandarin. But when the clerks didn’t understand her and responded with questions she didn’t understand, Maya used Mandarin to say that she was born in China, then adopted by her American mom. Even if her words were the right ones, what she was saying lost her meaning along the way.

“We’d say we are from America and they’d be giving us looks like ‘what are you trying to do, make fun of us or something?’ ” Maya told us when she got back to the hotel.

“I don’t think they understood we are Chinese but we live in America,” Jennie added.

“Or that our parents could be American,” Maya chimed in. “It’s hard to explain, and a lot harder without our parents because they give away that we are different in that sense.”

These early encounters gave the adoptees a keen understanding of how challenging it was going to be to explain themselves to Chinese people they’d meet. In America their faces say to strangers that they are Chinese. Hearing them talk establishes them as Americans pretty quickly. People who don’t know them might assume their family is Chinese, too, and from that assumption tumble others, some of which are tiresome for Jennie and Maya to hear given that their actual lives don’t always match expectations. Some assume that they focus their study on math and science since these subjects are ones in which Asians tend to excel. When many of their fellow students are Asian, a teacher might assume that all have the same style of learning and dogged determination to achieve at the very highest level. Teachers’ perceptions of their Asian students don’t often fit as well with Chinese adoptees as with those being raised by Chinese-American parents. Often Chinese families and adoptees’ families will have different approaches and ideas about how children learn best. They might even disagree over how to define learning.

Assumptions are made about cultural traditions based on how a person looks. Yet Chinese daughters in Caucasian families living in communities without many Asians are not likely to be living such predictable lives. Nor will their childhoods mirror those of daughters and sons who have Chinese-American parents. Nor do these adoptees’ lives resemble those of immigrant Chinese families who are adjusting to life in America.

Beginning when Jennie was quite young, she went to Hebrew classes on weekdays after school. She did this to prepare for when she would be 13 years old and would celebrate her bat mitzvah, a tradition in her family’s Jewish faith. On that day her extended family came from near and far to be with her, as did her “sisters,” the girls adopted with her from China. By then, each of those girls viewed her life through the experiences that her Caucasian family had exposed her to. Habits and interests were shaped more by friends and family than by exposure to Chinese heritage and culture. A few years after her bat mitzvah, Jennie went with friends to the Jewish state of Israel, several years before she went back to China.

When they were growing up, Jennie’s and Maya’s families exposed them to Chinese culture. When they were babies and toddlers, stories about China and adoption were read and told to them. We played with Mandarin flash cards—characters on one side, words in English on the other—and gave them singalong language and culture videos that they watched on TV. Maya attended a weeklong Chinese Culture Camp each summer, and to celebrate Lunar New Year we joined families like ours at elaborate banquets. The girls watched a lot of lion and dragon dances. When she was 7, Maya began performing Chinese dances, and she still does. Yet, all we did to acquaint our girls with Chinese culture did not leave them feeling part of a Chinese family or a Chinese community.

So when Jennie and Maya arrived home in China, each explored her identity in new ways. For teens to attain a sense of identity means sifting through all that has gone into making them the unique individuals they are. That begins at birth. Being raised in Caucasian families, Jennie and Maya saw their faces reflected in mirrors but they did not see faces resembling theirs in those who love them dearly. Desire for such connection is strong in all of us. So it’s not surprising that adoptees from China are coming together in supportive ways as they go to college and begin their work lives. For many, it’s the first time they find themselves apart from their families and with those they meet identifying them first by their Chinese faces.

A Road Less Traveled

On that June day in 1997 when our families landed at Boston’s Logan airport, we said we’d keep our daughters in touch as years went by. Somehow, even then, we understood it would matter to them that we did. And it has.

Since 1988, when foreigners began adopting from China, many of the estimated 120,000 adoptees have returned to China. (American families have adopted about 80,000 of these children.) Many have gone on homeland tours that mix exposure to Chinese culture with sightseeing. A lot of adoptees add a visit to their orphanages to the itinerary. Those who lived with foster families while in the orphanage will try to reconnect. When they get to high school, a few adoptees live with families in China or go there to study in the summer; many more do this in college. Others volunteer in orphanages, where some spend time with children who live where they did as babies.

More recently, adoptees have gone back to where they were abandoned. For most, it’s been the first necessary step to take when trying to locate an unknown birth family. The adoptee plasters posters written in Mandarin with the orphanage’s baby photo on walls of town buildings with information telling what is known. Families will come forward to say the child is theirs, but DNA tests must be used to find out if the claim holds up. When it does, a reunion happens. Among those who’ve searched, a few adoptees have succeeded.

Much rarer is the journey like the one Jennie and Maya made “home.” The tug of biological connection leads more adoptees to want to search for birth parents than does curiosity about what being a daughter there might have been like. Yet as Jennie and Maya found out in forming friendships with these girls and feeling welcomed by people in this place where their lives began, there are emotional rewards to be had in such a journey. For the Chinese girls, what was so familiar to them felt special and new when shared with their foreign friends. These friends gave them a bridge to a world they would understand better after getting to know girls who’d come “home” from America.

The American and Chinese girls wrote about what this experience meant to them.

“I grew up in a suburb with limited diversity,” Jennie wrote. “Being a Jewish and a Chinese immigrant attracted a plethora of questions and unwanted attention. To fit in with my friends and peers, I began conforming to social norms. As a result, over the years, I lost my sense of culture and began to identify more as American than as Chinese. When offered a chance to return to China, I jumped at the opportunity to try to rediscover my identity as a Chinese American. Before the trip I did not know what to expect. I was afraid that I would return to the town that influenced so much of my childhood and not feel any different. However, when I returned to Xixiashu, I felt an immediate connection to the town and a strong desire to embrace the Chinese culture I had forgotten. I felt at home, because even though I had no memories of Xixiashu, I finally fit in with the majority. After years of being surrounded by people who do not look like me, I was able to recognize physical features that were similar to mine.”

Maya wrestled with her identity when she was with the girls in China, and wrote of the discomfort she’d felt at first. “ ‘So what are you?’ the [Chinese] girls asked me. ‘You look Chinese on the outside but you are American on the inside.’ At first, I detested this description,” Maya wrote. “If the substance of my being is not Chinese, I might as well be white. Once content with describing myself as ‘Chinese American,’ now I was hit with its vagueness. Where do I belong between being Chinese and becoming American? … For those I met in Xiaxi, family is blood and ancestry. ‘You do not know your real parents?’ strangers would ask me soon after we met, sympathetic and eager to help me find mine. ‘When is your birthday? What orphanage were you from?’ To me, their words ‘real mother’ sit heavy in my mind. Even if I’d spoken their dialect fluently, I am not sure I could have explained. I have a real mother, who raised me and loves me. My biological family might not be whom I romanticized them to be and finding such strangers would not instantly conjure love. Instead, it was in the welcoming care that countless strangers showed me—in placing watermelon slices in both of my hands, pulling a comb through my hair, and attempting to cool me in 110-degree heat—that I found home in Xiaxi, and that was enough.”

A few days before Jennie left Changzhou to head back to America, her friend Jin Shan gave her a diary she’d written for her in Mandarin.

Shan’s words close our story: “Thank you, Jennie, for returning to your motherland after 15 years. We are in different countries, but I believe our friendship won’t have any barrier and will exist forever. It’s time to say goodbye and it’s hard to say goodbye, so there is another poem to say that, I don’t know how to translate that, but it’s something like this to say it’s hard to say goodbye. ‘And the wind will blow and the flowers will fall.’ So Jennie, when you are in the other country, please remember in China, there is another girl whose name is Jin Shan and she is in the land which you are familiar with and she prays for you and misses you. If we cannot meet each other in our life, please let’s have a chance to meet together in the next life. Jennie, I wish you happiness every day and that everything is well with you. I wish every dream of yours comes true. I also wish you be healthy and happy. I also wish our friendship will last forever and I wish our two countries can always be at peace. So, the lovely Jennie, the pure Jennie, say goodbye. So please remember Xixiashu always welcomes you back and Jin Shan misses you, and please be happy. Miss you. Jin Shan.”

Read more about Touching Home in China.