- India

- International

India’s dung courts, a whiff of nostalgia

Between the clay of France and the grass of England, as the tennis world gets busy debating surfaces, Shivani Naik remembers that humble and uniquely Indian surface — the extinct cow dung court.

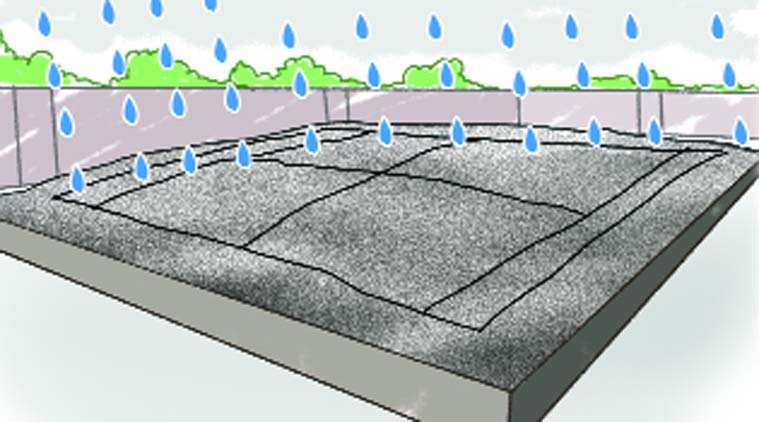

The first rain showers are a signal to the markers to bring out their spades as the existing layer balloons up and is easy to scrape off. The courts are filled with sand for four months of the monsoons and temporary markings made.

The first rain showers are a signal to the markers to bring out their spades as the existing layer balloons up and is easy to scrape off. The courts are filled with sand for four months of the monsoons and temporary markings made.

Tennis’ own Santana — Madrid man, Manolo – crooned the sport’s most enduring jingle right before he won the 1966 Wimbledon: The grass is just for cows. In subsequent years it caught on, like a catchy tune would —Ivan Lendl, Marcelo Rios and Marat Safin would do variously droll, disdainful and dramatic covers of that little ditty. Had Santana fetched up in India during his playing years, the sassy Spaniard might have deadpanned: The cows are for the dung, and the dung is for the tennis courts. Between the French Open and the Wimbledon when the tennis world gets busy debating surfaces and the majestic sovereigns who might or might not lord over the red dust and the green grass, we remember that humble and uniquely Indian surface — the cow dung court.

Like most things that were adored from India’s notorious 90s — partly because of how ridiculous they sound now, and secretly because how glad we are to see them gone — tennis’ cow dung courts would disappear from the scene in the last decade of that century, leaving behind a faint whiff of nostalgia. The dung courts, of course, left more than a whiff.

They are a part of India’s tennis history scarcely known to the public that guzzles Grand Slams off television sets and sports bars, while drawing battlelines between the Federer faithful and the Nadal nuts. Virtually unknown to the TV tennis-watchers, cow dung courts however strike an instant connect with those who played the sport at even the club level in the last century. The last time the slime-surface cropped up in tennis-talk was when Sania Mirza recalled her journey to the No. 1 spot in doubles rankings, wryly recounting how the first court she set foot on was a cow dung one. She might well be the last generation of the country’s tennis superstars to have even seen the dung courts, as India scraped off the last remains of the peeling, brown-filmed natural courts, slapped on the deco turfs, and hopped onto the synthetic courts bandwagon. Mirza’s slant to the dung courts memoir is akin to what is the storied Serbian tale of starting out in dried-out swimming pools. It’s the kind of back-story that will be immediately picked up by a Western journo and turned into a scoopy headline. Cow dung courts were indeed a peculiar Indian invention with no known beginnings and scarce parallels in tennis’ backyards of Europe and America, as well as a source of constant horror to anyone who heard of them the first time. But talk to old-timers and Indian players (even from the metros) right upto those who roamed the Indian circuit well into the late 90s and ask them about that part of their cow plop past, and you’d be surprised at how fondly the dung courts get spoken of.

After the rain stops, a ditch is dug, and filled with three layers of crushed Porbandar stone. It is then rolled, dried and levelled. Water is slowly added and the surface is further rolled. After that the court is allowed to breathe and dry for a few days.

After the rain stops, a ditch is dug, and filled with three layers of crushed Porbandar stone. It is then rolled, dried and levelled. Water is slowly added and the surface is further rolled. After that the court is allowed to breathe and dry for a few days.

Ubiquitous to the west and southern India (though south had equal number of clay-courts while north was all grass), dung courts were de rigueur in Mumbai, Pune and Ahmedabad, and even glimpsed in Hyderabad and Chennai where the Krishnans and Amritrajs played their earliest tennis. “I won the India Open on dung courts in 1977 in Mumbai,” Vijay Amritraj recalls, boasting that it was his fourth on the surface since 1973. “I didn’t think it was crazy, but foreigners definitely did when they heard of it. They thought they needed a tetanus shot when they fall down,” he says with a wink. A dozen Nationals would be held on dung courts right upto 1996.

A wonderstruck Aussie

India played their 1969 Davis Cup tie against Australia at Bombay’s CCI on dung courts with Rod Laver in attendance, and the grand old Aussie would return to play an exhibition on the same surface in 1986-7 and remain fascinated at how the courts got prepared. Zeeshan Ali who partnered him at that exhibition as a colt of 15 or 16 with Anand Amritraj across the net recalls the Aussie’s wonderment.

“It was fascinating but a horror at the same time for the top foreign players. They would stand at a little distance and look on as the markers and maalis would roll up their trousers, bring the buckets full of processed dung and a broom in the other hand, then paint lines when the courts dried up and set it up,” he says. In fact when playing at cow dung centres, Indian players would rub their hands in anticipation playing the same trick over and over again.

“We’d be sitting there, waiting for them to come. Then they’d hear tales of germs and get freaked out by the smell,” he recalls. Indian players would hit the balls a little further and force the visitors to stretch and risk a fall. “We’d put the fear of God in them the first year they came. Of course by the second year, they wouldn’t fall for all the paranoia.”

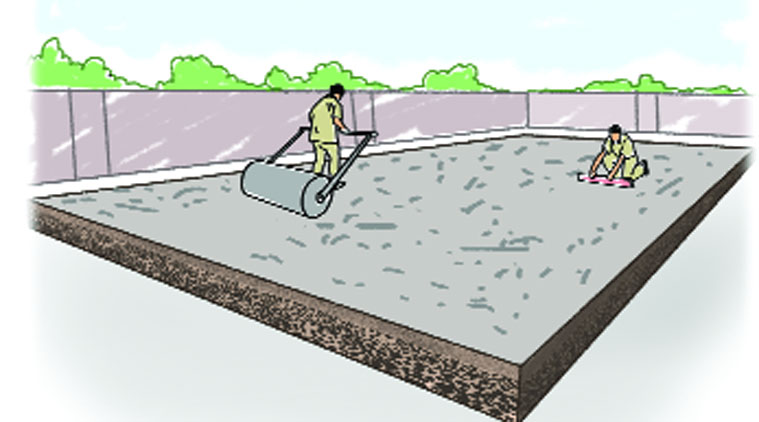

Before the cow dung paste is spread on the court, the surface is scrubbed and cleaned. The surface is then allowed to dry. The paste is made in a large barrell or drum with a bamboo stick used to mix dung and water. About 200 litres of dung is used in this process.

Before the cow dung paste is spread on the court, the surface is scrubbed and cleaned. The surface is then allowed to dry. The paste is made in a large barrell or drum with a bamboo stick used to mix dung and water. About 200 litres of dung is used in this process.

Various names are reeled off by different generations of players apart from Laver — from Tony Roche to Tim Henman, all of whom would step onto the courts cagily in pursuit of ranking points and money, like a tennis professional would. If you could get past the sights and smells, the surface was surprisingly a favourite of most Indian players.

“They were fantastic,” recalls former player and coach Nandan Bal. “Fairly fast and good footing,” he says. Not too different from hardcourts, the ball moved faster and the bounce stayed even helping in timing when striking the ball. “Very true bounce. Courts played faster, helped serve and volley and totally suited my game. I loved it,” former Davis Cupper Gaurav Natekar says. The surface was kinder on the knees. In a greatly romanticised rave, a coach in his 50s compares walking on a cow dung court to a barefoot stroll on a dewy grass bank. “It’s beautiful,” he pays the ultimate tribute, even invoking petrichor: “Loved the smell, like the first rains…”An illusion that was summarily shut close by John McEnroe.

In his first month as Davis Cup captain of the US team, McEnroe’s pre-tour words on the subject would blow up into an international ‘incident.’ Scheduled to travel to Zimbabwe for their first round tie of 2000, tennis’ baddest boy would declare that ‘Our worse case scenario has just taken place. We need like 27 shots or something to go down there.’ He would tell reporters that he expected the African nation to “pick a surface that they feel they have the best chance of beating us on which will probably be cow dung …”

The Zimbabwean government, under international politics’ baddest boy Mugabe was promptly outraged and would declare his comments as disparaging before proceeding to question just what must be going on inside his head.

Africa, in fact, had several dung courts which were in fact the same base as India, but bound by molasses. Prior to that Tom Gullikson, another US Cup captain, had to persuade his boys to come down to India, drawn to play them in the first round in the 1994 draw.

“It’s going to be a formidable trip, and while I’m certain we have the players to subdue India, the main task is getting people down there and keeping them healthy,” he would say before heading out, apparently memories of food poisoning and the dreaded dung courts during his 1977-8 sojourns making him a wary shepherd of the reluctant flock.

4The film is spread with a mop and then markers sweep it into evenness. Each layer should be applied only after the drying of the earlier layer. A fresh coat of cowdung is needed twice a week. 18-20 workers are needed for a court preparation.

4The film is spread with a mop and then markers sweep it into evenness. Each layer should be applied only after the drying of the earlier layer. A fresh coat of cowdung is needed twice a week. 18-20 workers are needed for a court preparation.

Lleyton Hewitt, when once choosing to blow his top about the slow surface at the Australian men’s Hardcourts event at Memorial Drive in Adelaide, would vent his frustration by calling them cow dung courts. He’d reckoned that his recent No 1 status and a couple of Slams would have had some pull in deciding the surface, but the authorities had given him a bafflingly slow surface and he would drag the poor dung courts in the jousting with his federation.

Clearly, he wasn’t keen on gaining Laver’s all-court tag that had on its resume – astro-turf, synthetic grass, green clay, red clay, cement, courts carved out of hockey rinks, hardwood besides the Indian cow dung. Henman would later call his India visit over the 1993-4 winter a turning point in his career. He’d play four tournaments, win three, lose the only one on grass at Chandigarh, and speak wistfully about the cow dung court at Ahmedabad.

Maybe, winning on the dung court took the stink out of the whole trepidation.

Surface tension

The mystery of the cow dung court extended to its classification for foreign officials and refs who travelled to India and found it an almighty headache. Harder than clay, but softer than the hard courts, the dung courts were difficult to bracket. They’d play as true as hardcourts, but look like clay on which you couldn’t slide. “From perception of categorisation, foreign supervisors would call it ‘clay’. But for the ball mark inspector it was a Herculean task to locate the ball marks,” India’s top officiating ref Nitin Kannamwar says. It would become clear after a certain degree of drying and then disappear. “They’d come scratching their heads — Is this asphalt? Is this concrete? But worse off were the tournament doctors who would have to deal with the paranoid foreign players.” The Indians, on the other hand, couldn’t stop falling in love with their truly “home” surface. SP Mishra, Indian selector and former player and coach, recalls how his father built him a court in Hyderabad way back when he started. “My father had many cows and buffaloes at the cowsheds. I remember the maalis would put 100s litres in a huge drum and mix it. When laid out on the prepared court it would look clean brown and yield perfect bounce. Back then labour was available. But now, there are no cows or buffaloes and not enough labour,” he says.

While cow dung courts in Hyderabad — including the Fateh Maidaan Sania Mirza played on — had a base of the red Murrum stone that’s pervasive across the southern Nawabi city, Mumbai relied on the egg-white ornamental Porbandar stone that the British used in their buildings. MK Sethi would lay out over 100 cow dung courts around September-October each year going around western India, relaying surfaces.

Fifty tonnes of Porbandar would go into a court — sourced chiefly from 50-100 year old buildings in South Bombay and Md Ali Rd that would collapse or be brought down for new construction.

“My trucks would reach there when I heard a building was down, and I once picked 1,000 tonne from a railway building off Badhwar Park in Colaba. We’d get the cow dung from cow sheds in Girgaon or Andheri for 3-4 thousand. 15-20 workers would work on it, and a new court would cost Rs1.5 lakh, with Rs 20,000 for maintenance.

“They were tough to maintain, and meticulously made,” he recalls. Markers became legends around local courts (known for their perfect surfacing) with Pune’s Raghoba Rao and Popat Rao being venerated and respected for their work that matched the courts of Mumbai’s posh CCI and Bombay Gymkhana. However, with the US and Australian Open being beamed into homes with their colourful surfaces gleaming through the tube, the hankering for hardcourt synthetic surfaces would gain in decibel. Indian players would demand faster surfaces at home to compete internationally. At the same time, cowsheds would leave Girgaon and move to Vasai-Virar on the outskirts of Mumbai and the RTO would get strict with bullock-carts ferrying the dung. By the turn of the century, most courts would opt to go synthetic.

“It was lay them, forget about them as far as maintenance went,” Ramesh Shinde of MSLTA says. India would lose its “home” advantage of the bucolic court binder in Davis Cups. “Unless it was GB or Australia, all other countries played on clay or hard courts. So courts, balls were the same for everyone, players got used to all weather conditions. India’s only advantage — our courts was lost,” Zeeshan says.

India would become more pleasant for foreigners to travel to and play on. Not that desi players ever seemed apologetic about their “home courts.” Ramesh Krishnan famously parried a poser when on one of his trips abroad.

“Do you guys really play on court with cow dung on it in India?” he was asked. “It’s all bull shit,” he shot back.