- India

- International

My friend Sarojini: Let’s teach our children to own History

History is not about great men doing things. Let’s teach our children to own it.

What if children realised they too could change the world?

What if children realised they too could change the world?

By Mathangi Subramanian

When you’re an anganwadi student in Bangalore, you learn lots of ways to say the English alphabet. A particular favourite of mine was the freedom fighter version, which goes like this:

A-B-C-D-E-F-G

G is the name of Gandhiji.

H-I-J-K-L-M-N-O-P

P is the name of Panditji.

Q-R-S

T-U-V

V is the name of Vajpayeeji.

The kids never seemed to get past V, so I’m not sure how it ends. But every time I hear it, I think about the way the students reciting it will learn history for the rest of their lives: as a disjointed series of great men whose virtues make them superhuman. Taught this way, history is something distant and faraway. Likewise, revolutionary change is painted as something only the most impressive of people achieve, an activity that anyone like you or me could never hope to join.

When researching my novel, Dear Mrs. Naidu, I encountered a very different kind of history. In my book, the protagonist, a 12-year-old schoolgirl, writes letters to Sarojini Naidu, the famous freedom fighter and poetess. Not much has been written about Naidu, so to find out about her life, I had to go straight to the source: the letters she originally wrote to her husband, friends, colleagues, and, of course, her children.

The Naidu I encountered in these letters astonished me. Not because of her wit or the strength of her convictions or her talent with words — although these were evident as well. The thing that impressed me the most was her sheer humanity. She was clever, playful, and never took herself too seriously. She was childlike, in the best sense of the word.

The Naidu I met stole into the jungle to catch a baby mongoose to cheer up her ailing daughter. (They named the mongoose Bela Kuhn after the famous Hungarian revolutionary.) When a crate of mangoes was delivered to her house right before she left for a holiday, she and her children took them to the train station and walked up and down the cars presenting mangoes to strangers and making new friends. When she heard that a friend of hers was in New York City while she was there on business, she left the state dinner she was attending, with her coat and shoes in hand, to fly up Fifth Avenue to a party which was definitely much more fun.

Perhaps most importantly, the Sarojini Naidu I met was not perfect, often doubting herself and her abilities. Even as she defied expectations, fighting ill-health and sailing around the world as the foremost ambassador of India’s revolution, she worried that she wasn’t paying enough attention to her children or her husband or her health. Even as she quietly criticised such luminaries as Gandhiji and Panditji, she wondered if her poetry —what she saw as her true life’s calling — was any good. And even as she penned speech after speech on the importance of solidarity between races and religions and girls’ education, she wondered whether it was all worth it, and whether anything would ever change.

In short, the Sarojini Naidu I met was flawed, but also determined. She was, in fact, a lot like me. She was a lot like all of us.

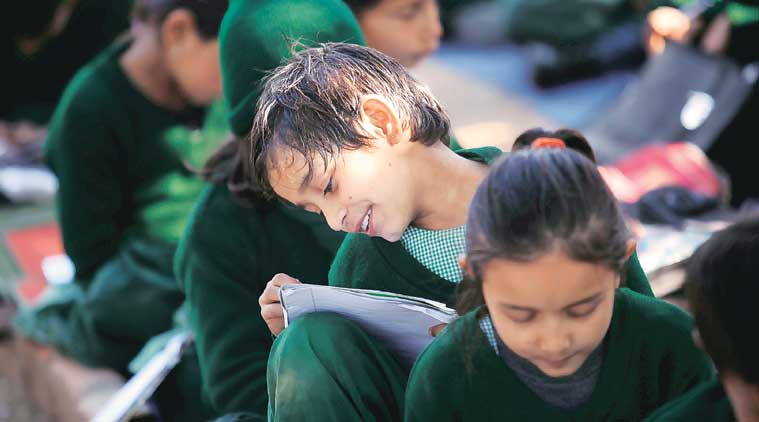

More than anything, reading her letters made me think of the young girls I’ve befriended over the years in anganwadis and government schools throughout India. I thought about how silly these young women could be, imitating their teachers and parents by wagging their fingers or cocking their hips, choreographing Bollywood-style dances with plastic toy vegetables and rubber balls, and making up songs about something as trivial as the sambar served at lunch. But I also thought about how strong they could be, resisting fathers who wanted to pull them out of school, or mothers who wanted them to stay home to look after younger siblings instead of going to class. Perhaps they did not have the wealth or education or prestige of Sarojini Naidu, but they certainly had the same sense of humour, the same resilience, and the same hunger for change.

What if, I thought, instead of reciting lists of great men in history class, these girls got to read Sarojini Naidu’s letters? What if they, like me, realised that freedom fighters are just people like the rest of us? What if they, like me, realised that the quiet revolutions led by children are the seeds of much larger revolutions that are yet to come?

What if they realise that changing the world is not something relegated to extraordinary people but is, in fact, just a matter of ordinary people doing extraordinary things?

Now that, I think, would be truly extraordinary.

Mathangi Subramanian is a writer and an educator in Delhi

More Lifestyle

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05