- India

- International

Tree-some: A day in the life of Antar Singh

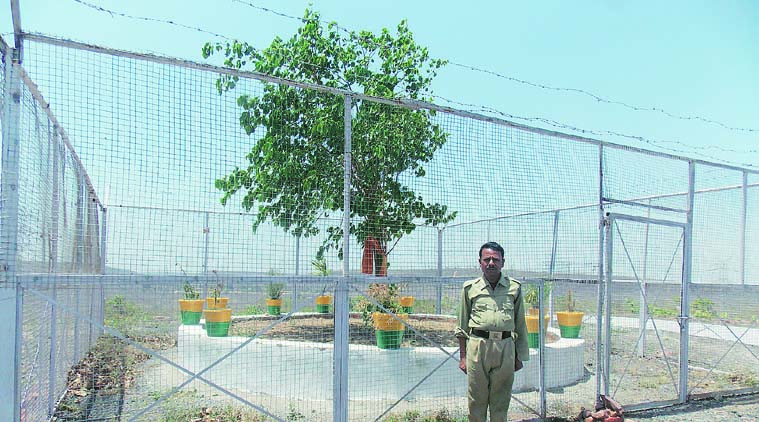

It is a little tedious at the top for four men guarding the sacred Bodhi tree on a hillock near Sanchi — but for music and meals.

It is a little tedious at the top for four men guarding the sacred Bodhi tree on a hillock near Sanchi — but for music and meals. (Express Photo by Milind Ghatwai)

It is a little tedious at the top for four men guarding the sacred Bodhi tree on a hillock near Sanchi — but for music and meals. (Express Photo by Milind Ghatwai)

A few kilometres from the world heritage site of Sanchi, a sacred tree is taking root on a hillock. The Peepal sapling was planted amid fanfare by then Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa on September 21, 2012. Since then silence has stretched over the vast hillock that overlooks the busy road between Bhopal and Sanchi, broken only by the chatter of four.

They are the home guards, whose task it is to never leave the Bodhi tree unattended, day or night, festivals and otherwise.

“Asaan hai, dekh-bhal hi to karni hai (It’s easy, I have to only tend to it),” shrugs 56-year-old ‘Sepoy’ Antar Singh.

The tree is ringed by a huge enclosure whose lock is opened only to water it — twice a day, morning and evening. A board next to the lane leading up the hillock pronounces the site as prohibited, and barricades regulate vehicular access.

Singh, who gets paid nearly Rs 10,000 a month, does his job with few questions asked. Most days for the four guards mean watching vehicles whiz by down below or in their tent pitched next to the tree.

When Rajapaksa got the sapling from Sri Lanka, he was returning, symbolically, a slice of history. The tree in Sri Lanka is said to have grown from the saplings carried by Emperor Ashoka’s son Arahat Mahendra and daughter Thera Sanghmitra there more than 2,000 years ago. The saplings were from a tree under which Lord Buddha is said to have attained enlightenment.

One such sapling from the Bodhi tree was gifted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to a monastery in Mongolia during his recent visit there.

At various points in his career as home guard, Singh had been deployed during elections, riotous situations or traffic management in Raisen district, but never before had he been asked to guard a subject that does not move or talk.

Once in a while, VIPs visiting Sanchi also drop by, but the 56-year-old does not really know the significance of what he is guarding.

The hillock had been chosen as this was meant to be the site of the Sanchi University of Buddhist and Indic studies, spread over 100 acres with a budget of Rs 300 crore. Laying the foundation stone, Rajapaksa had said the tree in Lanka from which the sapling had come was accepted as the oldest historically recorded tree in the world.

The university has begun functioning, but from a rented place a little more than 10 km away, with the tree the only reminder of the proposed grand venture.

The sacred tree on the hillock (top); Singh doesn’t really know its significance. (Express Photo by Milind Ghatwai)

The sacred tree on the hillock (top); Singh doesn’t really know its significance. (Express Photo by Milind Ghatwai)

The most valued thing in the guards’ 12X12 feet tent is a small key to the tree enclosure. It dangles from a clothesline. Another possession is a register that maintains duty chart and, more importantly, contains telephone numbers of police, administration, fire brigade and panchayat officials. The guards keep in touch with the Salamatpur and Sanchi police stations. The tent has a temporary electricity connection.

The four have separate bedding and utensils inside.

A 1,200-litre tanker stationed near the tent is refilled every three-four days by a fire brigade tender that comes around. It’s the only source of water for the tree and guards.

At least 7 km away from the nearest habitation, the guards have to find ways to while away time, and most of it is spent cooking at leisure.

There is no television set in the tent or radio. Songs on mobile phones are the only source of entertainment. Bollywood ones are his favourite, Singh smiles.

After he wakes up around 6-6.30 am, the first thing Singh does is water the tree. Generally, it is he who performs this task. “Mornings are pleasant here,” he says.

A short stroll and a brief chit-chat with fellow guards later, he goes inside the tent around 8.30-9 am. He admits he lingers over the lunch-making that follows. “I take around an hour or so because I have enough time on hand.” They all skip breakfast.

Food is made on a makeshift chulha. It takes longer, but Singh isn’t complaining. “Food cooked on wood is simply the best.”

Around 10-10.30 am, after the lunch (generally daal-chawal or sabzi-roti) is made, Singh takes a bath near the tanker. Even while bathing, Singh notes, he can keep a watch on the tree. While he is not very religious, Singh doesn’t eat before bathing.

Having eaten nothing since morning, they take their lunch before noon.

The afternoon rest can stretch for more than an hour. “We sit and talk because there is nothing else to do,” Singh says.

Before evening falls, the conversation has already moved on to dinner. Singh doesn’t have tea, unlike the others. Only one job is left before they start making dinner preparations: watering the tree again.

A lazy dinner-making hour later, Singh eats between 8.30 and 9 pm, often with the others. They all retire to bed by 10 pm, with officially one keeping watch at night.

Breaks from work are rare, mostly involving a trip to Sanchi to buy vegetables. Singh also occasionally visits his village Khairi, about 100 km away. “I never get bored because I know this gets me my bread and butter,” says the father of two, who was posted here nearly a year and a half ago.

A few months ago, when the tree leaves started wilting and a threat of survival loomed, the guards were told to strictly monitor it and quickly get in touch with officials if they found something amiss.

“I have faced no difficulties so far,” Singh asserts, adding without a pause, “We are trained. It’s a habit to do what we have been asked to do.”

The weather, though, is an issue, Singh admits hesitatingly. In summer, the mercury routinely crosses the 40 degree mark. The guards often go around shirtless, Singh laughs. Should anyone come visiting, they get enough of a headstart to put something on, situated as they are on a hillock.

While the distance between the main road and the tree is just a little more than 250 m, it’s a steep climb on foot. “The guard who is on duty wears the uniform while the rest wear their own clothes,” says Havildar Narayan Sharma, the “team leader”. Due to retire in a few months, Sharma is more open about their current assignment. “It is tedious, but duty means we can’t complain.”

Singh has now forgotten when he joined the Home Guards, or what exactly his training involved. “Many parades and wielding batons,” he says, distracted.

“But duty is duty,” he adds, craning his neck out the tent for a quick look at the tree. “Pet paalna hai to hisab-kitab karna padta hai (To survive, one has to see everything in balance).”

Buzzing Now

May 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05