A Picture of Karnataka

By: Chandan Gowda

Assembling a collage of landscape, local histories and myths, The Emerald Route still remains the best book of general introduction — in English — to Karnataka

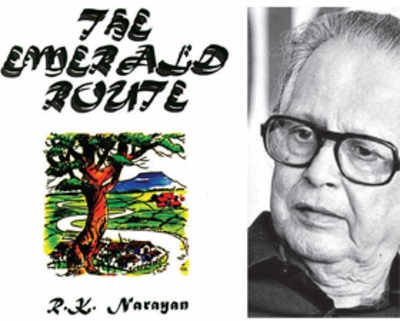

R K Narayan ’s The Emerald Route still remains the best book of general introduction (in English) to Karnataka since its appearance nearly four decades ago (1977). The Department of Information and Publicity commissioned him and his brother, RK Laxman , the cartoonist, to write a book on the state (The 1999 Penguin reprint of this book leaves out Laxman’s illustrations).

In his post-script, RKN writes that he chose not to record his personal experiences, as the book would then become “part of an autobiography,” and had “tried to be impersonal.” But The Emerald Route is really a deeply personal book: it singles out facts and stories that its author views as essential for conveying the spirit of the state.

The religious pluralism of the place attracts RKN deeply. He narrates how the cave containing the tomb of Baba Budan, “a Muslim saint” from “Arabia,” who brought coffee with him (and helped “the beginning of coffee cultivation in India”), in Chikmagalur was also sacred to local Hindus who believed that Dattatreya had disappeared into it. And, those curious about how a Jain family happens to be the trustee of the Manjunatheshwara temple at Dharmasthala will find an explanation in his book.

Nearly all of the discussion of the districts that make up Southern Karnataka is brought over verbatim from Mysore, his book from 1938. Such a transfer is more easily done, of course, when those places had been introduced mostly through local myths and dynastic lore. The introductions to the coastal regions, Coorg and North Karnataka, which had not formed territorial part of the Old Mysore State, are the freshly written parts of the book but merge unnoticeably with the older descriptions in tone and style. RKN’s work of making his book representative of the newly expanded state of Karnataka is neatly achieved.

“As a little change from my own descriptions,” RKN writes that he asked his brother, RK Laxman, “to record his impressions” of Belgaum, Dharwar and Hubli. As consequence, we get to hear of a temple for Shoorpanakhi, Ravana’s sister, in Supa, a village near Dandeli, which had submerged in the river Kali after being built in 1873 and emerged every few decades to be seen by her devotees.

The Emerald Route includes three delightful appendices written by RKN: a radio script, a short play and a short story. The radio script gives a finely detailed account of Khedda, the now discontinued practice of capturing elephants in Mysore. In this graphic account of the famed sport, the ironist in RKN does not fail to note the indispensable role of trained elephants in capturing the wild ones and the prayer offered to Ganesha, “the Elephant-faced god,” at the start of the Khedda.

Watchman of the Lake, is RKN’s short, one-act play based on a folk story where a villager offers himself in sacrifice to prevent a powerful flood from submerging a kingdom. Little known folk tales sit easily along with canonical ones in the book. (Indeed, the book begins with the famous folk song, Govina Haadu (“The Song of the Cow”) which holds up Karnataka as a region at the centre of the earth and where one kept one’s word). In the third appendix, The Restored Arm, RKN makes a short story out of a legendary episode: Jakanachari, the chief sculptor of the Belur and Halebid temples, is exposed by a young man (who is later revealed as his son) for not being discerning in his choice of stone for Krishna’s idol. Unlike in the original, though, the son prevents his father from chopping off his right arm when his oversight becomes known.

RKN’s loving and careful portrait of Karnataka glosses over the violence underlying the formation of its cultural world. The military episodes involving the major dynasties like the Chalukyas and the Adil Shahis and rulers like Tipu Sultan seem instances of local heroism more than anything else.

The book’s postscript, however, shows the author’s clear recognition of the violence of modern economic processes and introduces a note of concern to what might otherwise appear a feel good picture of Karnataka. RKN shows deep ecological sensitivity: “I cannot put pen to paper nowadays without thinking of all the cutting, crushing and destruction that has gone on in order to provide me a sheet of white paper.” A little later, he says, “Modern developments and projects are threatening to render animals homeless… I can now almost hear the remark, ‘Should we go back to cave-dwelling and live on berries and roots or turn Cubbon Park over to bears and tigers?’ I have no answer to such a remark but have only this to say, ‘Surely there must be a way of utilizing resources without destroying the sources.’”

The author is Professor of Sociology, Azim Premji University

Assembling a collage of landscape, local histories and myths, The Emerald Route still remains the best book of general introduction — in English — to Karnataka

RK Narayan (RKN) notes happily that the government left him and his brother “totally free to write (and sketch)” as they liked. What we get, as a result, is an introduction to the state through descriptions of landscape sewn together with local historical and mythological episodes. There is little engagement with contemporary politics or culture in Karnataka. The freedom struggle, the movement for the state’s unification, the Emergency, the political and literary figures and artists: none of these find mention anywhere in the book.

In his post-script, RKN writes that he chose not to record his personal experiences, as the book would then become “part of an autobiography,” and had “tried to be impersonal.” But The Emerald Route is really a deeply personal book: it singles out facts and stories that its author views as essential for conveying the spirit of the state.

The religious pluralism of the place attracts RKN deeply. He narrates how the cave containing the tomb of Baba Budan, “a Muslim saint” from “Arabia,” who brought coffee with him (and helped “the beginning of coffee cultivation in India”), in Chikmagalur was also sacred to local Hindus who believed that Dattatreya had disappeared into it. And, those curious about how a Jain family happens to be the trustee of the Manjunatheshwara temple at Dharmasthala will find an explanation in his book.

Nearly all of the discussion of the districts that make up Southern Karnataka is brought over verbatim from Mysore, his book from 1938. Such a transfer is more easily done, of course, when those places had been introduced mostly through local myths and dynastic lore. The introductions to the coastal regions, Coorg and North Karnataka, which had not formed territorial part of the Old Mysore State, are the freshly written parts of the book but merge unnoticeably with the older descriptions in tone and style. RKN’s work of making his book representative of the newly expanded state of Karnataka is neatly achieved.

“As a little change from my own descriptions,” RKN writes that he asked his brother, RK Laxman, “to record his impressions” of Belgaum, Dharwar and Hubli. As consequence, we get to hear of a temple for Shoorpanakhi, Ravana’s sister, in Supa, a village near Dandeli, which had submerged in the river Kali after being built in 1873 and emerged every few decades to be seen by her devotees.

The Emerald Route includes three delightful appendices written by RKN: a radio script, a short play and a short story. The radio script gives a finely detailed account of Khedda, the now discontinued practice of capturing elephants in Mysore. In this graphic account of the famed sport, the ironist in RKN does not fail to note the indispensable role of trained elephants in capturing the wild ones and the prayer offered to Ganesha, “the Elephant-faced god,” at the start of the Khedda.

Watchman of the Lake, is RKN’s short, one-act play based on a folk story where a villager offers himself in sacrifice to prevent a powerful flood from submerging a kingdom. Little known folk tales sit easily along with canonical ones in the book. (Indeed, the book begins with the famous folk song, Govina Haadu (“The Song of the Cow”) which holds up Karnataka as a region at the centre of the earth and where one kept one’s word). In the third appendix, The Restored Arm, RKN makes a short story out of a legendary episode: Jakanachari, the chief sculptor of the Belur and Halebid temples, is exposed by a young man (who is later revealed as his son) for not being discerning in his choice of stone for Krishna’s idol. Unlike in the original, though, the son prevents his father from chopping off his right arm when his oversight becomes known.

RKN’s loving and careful portrait of Karnataka glosses over the violence underlying the formation of its cultural world. The military episodes involving the major dynasties like the Chalukyas and the Adil Shahis and rulers like Tipu Sultan seem instances of local heroism more than anything else.

The book’s postscript, however, shows the author’s clear recognition of the violence of modern economic processes and introduces a note of concern to what might otherwise appear a feel good picture of Karnataka. RKN shows deep ecological sensitivity: “I cannot put pen to paper nowadays without thinking of all the cutting, crushing and destruction that has gone on in order to provide me a sheet of white paper.” A little later, he says, “Modern developments and projects are threatening to render animals homeless… I can now almost hear the remark, ‘Should we go back to cave-dwelling and live on berries and roots or turn Cubbon Park over to bears and tigers?’ I have no answer to such a remark but have only this to say, ‘Surely there must be a way of utilizing resources without destroying the sources.’”

The author is Professor of Sociology, Azim Premji University

GALLERIES View more photos