- News

- City News

- mumbai News

- Development drives away Mumbai's featured songsters

Trending

This story is from May 10, 2015

Development drives away Mumbai's featured songsters

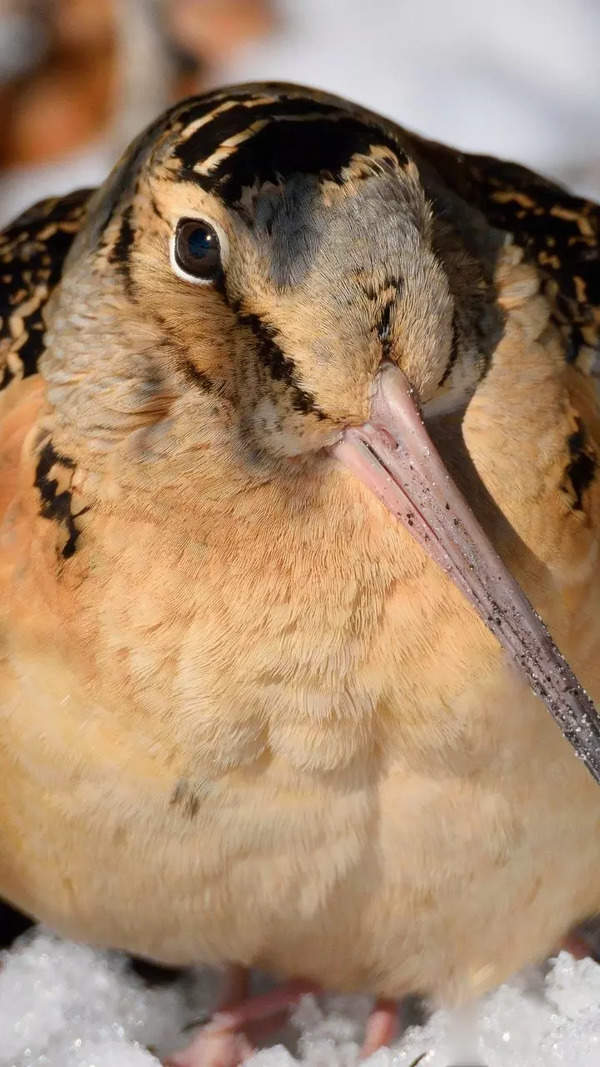

There is nothing flashy about larks: they are plain-looking, drab coloured birds, easily overlooked and lost in their bleak-looking openland world.

by Sunjoy Monga

There is nothing flashy about larks: they are plain-looking, drab coloured birds, easily overlooked and lost in their bleak-looking openland world. But what melodic singing the larks warble out, inspiring greatly loved prose and poetry.

In several countries, larks and their singing are ingrained in folklore. “If you hear a lark sing before breakfast you will be merry all day.” “To hear a lark sing is good luck.” “If larks fly high and sing long, expect fair weather.”

The Bard himself bequeathed several passages referring to the lark, full of sublime pathos and lofty concepts: “Like to the lark at break of day arising/From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate”; in Cymbeline: the sweet songster is the bird “singing at heaven’s gate” and the “bird of dawn”, and in The Merchant of Venice, Portia longs, proverbially, “to sing as sweetly as the lark”.

I had an amazing childhood in Mumbai, amid fields and skies of singing, melodic strutting larks I could not even identify then, though I knew there were several kinds. The grassy mudflats were vast, endless, along the Malad and Manori creeks. All of that is ruined, finished, indeed in the past two decades, heedlessly swamped under humongous development, rich wildernesses now covered with crumbling concrete, from Malvani to Dahisar and beyond.

Those tufted homelands of my childhood, a mix of unique saline flatlands, short grass and scrub, were so vast my friend Jos and I feared venturing too far out, no more than a kilometer, at most, from where our homes could be sighted.

Every summer, between March and May, and again during late September and October, we would come across many lark nests. There were at least three kinds regularly nesting, sometimes a fourth type too. Humble, shallow cups on the ground, at the base of short grass tussocks, or in the wavering shade of a clod of hardened earth, at times even in a cattle hoof-print, the lark’s nests seemed pretty much vulnerable and open to the elements, one might think.

After all, there were then many serpents, mongoose and jungle cats, jackals and several birds of prey on the openlands, predators all. But the larks could survive these winged, four-legged and legless brethren. It was us two-legged ones, and our impending explosion of development, for which they had no clue of how to face up to the sheer rapacity and rapidity with which their homeland would be obliterated.

Around my last years in school (mid-1970s), I had the luck to meet India’s great ornithologists, Humayun Abdulali and Salim Ali. With Humayun, there were many field visits, including into the openlands, and once in late March, on seeing so many nests, he remarked with delight, “Abhi tak itne lark Mumbai mein ghosla banate hai” (‘So many larks still make their homes in the city’).

A couple of days later, it was Salim Ali who came specially to see the larks breeding. He was as excited as a child in the field. On approaching one of the nests, an adult bird suddenly scrambled out, dragging its wings as if they were broken. Salim Ali explained to me that the bird did so as a diversionary tactic, to deflect any threat (in this case, us) from the nest.

Salim Ali, that day, recalled how, when he was younger, Humayun and he used to look at larks nesting, during the 1930s in today’s downtown Mumbai, around Churchgate, around Kurla, and commonly around Andheri and Santacruz.

The steady decline of the lark from Mumbai is indicative of the waning openland habitat. Larks were reported breeding on Churchgate reclamation areas up to the late 1930s, and regularly along some of the other openland sites, all through the early 1980s and then sporadically into the 1990s and early 2000s. Their decline is a tragedy that can be best summed up as the disappearance of innocence from Mumbai.

I have, in fact, probably heard my last lark song in mainland Mumbai.

It was in March of the year before last. A pair of ashy-crowned sparrow lark had taken off from under a bush on the openlands adjoining Thane creek. They flew overhead, with just a faint chirrup, to the east, towards the vast creek. Had they been breeding, I am sure they would have returned. We waited three hours. Again, the following day, we searched painstakingly, but there was no sign of them.

I have since checked every accessible site where larks were once routine, even breeding, but have not come across any singing or breeding; the winter visiting short-toed lark too was not seen this season in Greater Mumbai.

Such has been our celebration of ignorance, of Mumbai’s tufted openland world, of these feathered songsters, of all that innocent fun, that inspiration for poets and writers.

(Naturalist-photographer-writer, Sunjoy Monga has been documenting and interacting on the biodiversity and ecology of the Mumbai region, and elsewhere across India, for nearly four decades now)

There is nothing flashy about larks: they are plain-looking, drab coloured birds, easily overlooked and lost in their bleak-looking openland world. But what melodic singing the larks warble out, inspiring greatly loved prose and poetry.

In several countries, larks and their singing are ingrained in folklore. “If you hear a lark sing before breakfast you will be merry all day.” “To hear a lark sing is good luck.” “If larks fly high and sing long, expect fair weather.”

The Bard himself bequeathed several passages referring to the lark, full of sublime pathos and lofty concepts: “Like to the lark at break of day arising/From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate”; in Cymbeline: the sweet songster is the bird “singing at heaven’s gate” and the “bird of dawn”, and in The Merchant of Venice, Portia longs, proverbially, “to sing as sweetly as the lark”.

For me, larks symbolised the innocent fun of ‘Bombay’ times gone by. More than that, they awakened an awareness of teeming life in vast openlands across a city today choked with development. Hardly anything of the pristine survives about those openlands, and their larks.

I had an amazing childhood in Mumbai, amid fields and skies of singing, melodic strutting larks I could not even identify then, though I knew there were several kinds. The grassy mudflats were vast, endless, along the Malad and Manori creeks. All of that is ruined, finished, indeed in the past two decades, heedlessly swamped under humongous development, rich wildernesses now covered with crumbling concrete, from Malvani to Dahisar and beyond.

Those tufted homelands of my childhood, a mix of unique saline flatlands, short grass and scrub, were so vast my friend Jos and I feared venturing too far out, no more than a kilometer, at most, from where our homes could be sighted.

Every summer, between March and May, and again during late September and October, we would come across many lark nests. There were at least three kinds regularly nesting, sometimes a fourth type too. Humble, shallow cups on the ground, at the base of short grass tussocks, or in the wavering shade of a clod of hardened earth, at times even in a cattle hoof-print, the lark’s nests seemed pretty much vulnerable and open to the elements, one might think.

After all, there were then many serpents, mongoose and jungle cats, jackals and several birds of prey on the openlands, predators all. But the larks could survive these winged, four-legged and legless brethren. It was us two-legged ones, and our impending explosion of development, for which they had no clue of how to face up to the sheer rapacity and rapidity with which their homeland would be obliterated.

Around my last years in school (mid-1970s), I had the luck to meet India’s great ornithologists, Humayun Abdulali and Salim Ali. With Humayun, there were many field visits, including into the openlands, and once in late March, on seeing so many nests, he remarked with delight, “Abhi tak itne lark Mumbai mein ghosla banate hai” (‘So many larks still make their homes in the city’).

A couple of days later, it was Salim Ali who came specially to see the larks breeding. He was as excited as a child in the field. On approaching one of the nests, an adult bird suddenly scrambled out, dragging its wings as if they were broken. Salim Ali explained to me that the bird did so as a diversionary tactic, to deflect any threat (in this case, us) from the nest.

Salim Ali, that day, recalled how, when he was younger, Humayun and he used to look at larks nesting, during the 1930s in today’s downtown Mumbai, around Churchgate, around Kurla, and commonly around Andheri and Santacruz.

The steady decline of the lark from Mumbai is indicative of the waning openland habitat. Larks were reported breeding on Churchgate reclamation areas up to the late 1930s, and regularly along some of the other openland sites, all through the early 1980s and then sporadically into the 1990s and early 2000s. Their decline is a tragedy that can be best summed up as the disappearance of innocence from Mumbai.

I have, in fact, probably heard my last lark song in mainland Mumbai.

It was in March of the year before last. A pair of ashy-crowned sparrow lark had taken off from under a bush on the openlands adjoining Thane creek. They flew overhead, with just a faint chirrup, to the east, towards the vast creek. Had they been breeding, I am sure they would have returned. We waited three hours. Again, the following day, we searched painstakingly, but there was no sign of them.

I have since checked every accessible site where larks were once routine, even breeding, but have not come across any singing or breeding; the winter visiting short-toed lark too was not seen this season in Greater Mumbai.

Such has been our celebration of ignorance, of Mumbai’s tufted openland world, of these feathered songsters, of all that innocent fun, that inspiration for poets and writers.

(Naturalist-photographer-writer, Sunjoy Monga has been documenting and interacting on the biodiversity and ecology of the Mumbai region, and elsewhere across India, for nearly four decades now)

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA