- News

- The Bong connection

This story is from May 3, 2015

The Bong connection

Are sarson fields giving way to shorshe? A Punjufied Bollywood is now seeing a range of films crafted with a distinct Bengali sensibility.

Are sarson fields giving way to shorshe? A Punjufied Bollywood is now seeing a range of films crafted with a distinct Bengali sensibility.

Bangali samajhna bhool gaye hain kya doctor saab?” Toward the end of Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!, the cerebral, swash-buckling detective asks villain Yang Guang. It’s a throwaway line in the midst of a tense, climatic confrontation but it underscores the suspension of disbelief that director Dibakar Banerjee is asking us to extend. When the characters speak in Hindi (without any tinge of a Bengali accent), they are meant to be speaking in Bangla.As the director puts it: “It is exactly the way when I tell my daughter, ‘And the lion said…’. The lion can’t talk but me and my daughter are playing a game.” As I watched, I wondered: are we in the throes of the ‘Bengalification’ of Bollywood?

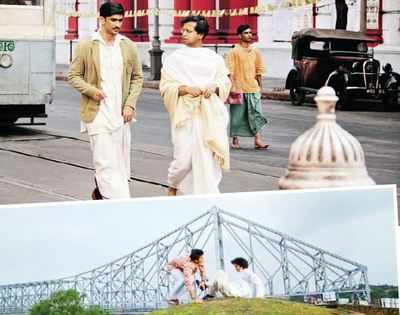

Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! is, of course, the most obvious example but in the last few years, Bengal, and specifically Kolkata, has seeped into Hindi cinema. Think of Sujoy Ghosh’s thrillingly tense Kahaani, in which ‘Bidya Bagchi’ avenged herself. Or Pradeep Sarkar’s period saga Parineeta, which is a lyrical, nostalgic trip to the Kolkata of the 1960s, complete with an item number performed by Rekha at the iconic night club Flurys. Or Anurag Basu’s Barfi!, in which a deaf-mute man and an autistic girl, somehow managed to live by themselves in the foreground of Howrah Bridge. And coming up is Shoojit Sircar’s Piku, in which a Bengali father and daughter, played by Amitabh Bachchan and Deepika Padukone, will teach us, as the promo says, ‘to release our emotion through motion.’

This isn’t the first generation of Bengali directors in Hindi cinema. Filmmakers like Bimal Roy, Hrishikesh Mukherji, Shakti Samanta, Basu Bhattacharya and Basu Chatterji created landmark Hindi films. Shakti Samanta gave us the definitive Kolkata song — Chingari koi bhadke in Amar Prem, in which a dashingly inebriated Rajesh Khanna propounds his philosophy of life to the beauteous Sharmila Tagore on a boat that bobs around Howrah bridge (I was saddened to hear that the song was actually shot in a Mumbai studio because the Kolkata authorities didn’t give Samanta permission to shoot on the river).

But this might be the first time that so many leading directors of Hindi cinema are creating movies with a distinctly Bengali sensibility. Bollywood has traditionally been a Punjabi stronghold, offering North Indian flavored fantasies — the swaying mustard fields, Karva Chauth and fair and handsome heroes. This norm has been occasionally challenged by directors like Sanjay Leela Bhansali who set two movies — Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam and Goliyon Ki Raasleela-Ram Leela, in highly stylized Gujarati worlds. But largely the Punjabi worldview prevailed.

It’s also tough to balance nuances and an authentic Bengali sensibility with the demands of mass entertainment that must have pan-India appeal. Purists were incensed by Dibakar’s interpretation of the iconic Bengali detective as a hero capable of back-flips and gasp, kissing. The decibel level of the debate was even louder than the flap over Bhansali’s interpretation of Devdas with Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan. Bengalis railed against the use or misuse of words like ‘shotti’ and ‘eesh.’

Interestingly, none of the current crop of Bengali directors is making hardcore, masala films. No Rowdy Rathores or Grand Masti for this lot. They work within the mainstream form but consistently tweak it. So Dibakar’s more austere, artsy vision is balanced by Anurag Basu’s romantic worldview and Shoojit’s Hrishida style middle class stories. What do all Bengali directors have in common? Says Dibakar: Indigestion. Pradeep has a similar answer: ‘Food and then indigestion.’

I think what unites Bengali directors is their ability to create compelling films with a human core. Their best work has an artless elegance. May their tribe increase — or in keeping with the mood — Unnato hao!

Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! is, of course, the most obvious example but in the last few years, Bengal, and specifically Kolkata, has seeped into Hindi cinema. Think of Sujoy Ghosh’s thrillingly tense Kahaani, in which ‘Bidya Bagchi’ avenged herself. Or Pradeep Sarkar’s period saga Parineeta, which is a lyrical, nostalgic trip to the Kolkata of the 1960s, complete with an item number performed by Rekha at the iconic night club Flurys. Or Anurag Basu’s Barfi!, in which a deaf-mute man and an autistic girl, somehow managed to live by themselves in the foreground of Howrah Bridge. And coming up is Shoojit Sircar’s Piku, in which a Bengali father and daughter, played by Amitabh Bachchan and Deepika Padukone, will teach us, as the promo says, ‘to release our emotion through motion.’

This isn’t the first generation of Bengali directors in Hindi cinema. Filmmakers like Bimal Roy, Hrishikesh Mukherji, Shakti Samanta, Basu Bhattacharya and Basu Chatterji created landmark Hindi films. Shakti Samanta gave us the definitive Kolkata song — Chingari koi bhadke in Amar Prem, in which a dashingly inebriated Rajesh Khanna propounds his philosophy of life to the beauteous Sharmila Tagore on a boat that bobs around Howrah bridge (I was saddened to hear that the song was actually shot in a Mumbai studio because the Kolkata authorities didn’t give Samanta permission to shoot on the river).

But this might be the first time that so many leading directors of Hindi cinema are creating movies with a distinctly Bengali sensibility. Bollywood has traditionally been a Punjabi stronghold, offering North Indian flavored fantasies — the swaying mustard fields, Karva Chauth and fair and handsome heroes. This norm has been occasionally challenged by directors like Sanjay Leela Bhansali who set two movies — Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam and Goliyon Ki Raasleela-Ram Leela, in highly stylized Gujarati worlds. But largely the Punjabi worldview prevailed.

Which is why it’s fascinating to see Kolkata take centerstage. The city has become both muse and leading character. The trams, coffee houses, crowded, snaking streets and the old world charm — topped, of course, by the iconic Howrah Bridge — translate into magic onscreen. With Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!, Dibakar says, his attempt was to explore the ‘pockets of adventure,’ that Kolkata has. When I ask him why filmmakers go back to the city, Dibakar explains: “In Kolkata, people have a life outside their jobs. The people who govern the city, the policemen, the civil servants, are great Kolkata lovers.” Dibakar gives the example of a senior official at the Kolkata port — when the crew applied for shooting permissions, the gentleman embarked upon a didactic analysis of Byomkesh versus Feluda. Meanwhile, Sujoy and Pradeep Sarkar wax eloquent about the ease of shooting in a city with a strong regional film industry, a city in which ‘hobe na’ (it can’t be done) actually means ‘hoye jabe,’ (we’ll manage it). The toughest part, Sujoy says, “is how many stories can we set in Kolkata?”

It’s also tough to balance nuances and an authentic Bengali sensibility with the demands of mass entertainment that must have pan-India appeal. Purists were incensed by Dibakar’s interpretation of the iconic Bengali detective as a hero capable of back-flips and gasp, kissing. The decibel level of the debate was even louder than the flap over Bhansali’s interpretation of Devdas with Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan. Bengalis railed against the use or misuse of words like ‘shotti’ and ‘eesh.’

Interestingly, none of the current crop of Bengali directors is making hardcore, masala films. No Rowdy Rathores or Grand Masti for this lot. They work within the mainstream form but consistently tweak it. So Dibakar’s more austere, artsy vision is balanced by Anurag Basu’s romantic worldview and Shoojit’s Hrishida style middle class stories. What do all Bengali directors have in common? Says Dibakar: Indigestion. Pradeep has a similar answer: ‘Food and then indigestion.’

I think what unites Bengali directors is their ability to create compelling films with a human core. Their best work has an artless elegance. May their tribe increase — or in keeping with the mood — Unnato hao!

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA