The first thing you notice slipping down the Congo River is the incredible light that seems to shine out of the immense, silent forest. Occasionally, a green pigeon or hornbill will fly over the primeval flood, eight miles wide in places, but otherwise you are as alone as you will ever be on this planet.

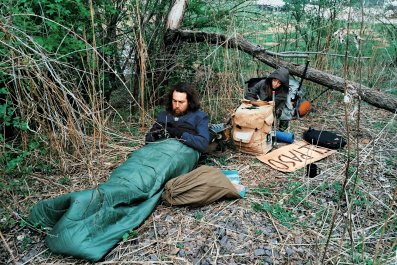

The country here is still a lost world. Time is suspended, and the magical becomes normal.My shy captain had no clock or compass, just a smoked monkey (snack) for company. His crew regarded me as part of their African family and made sure I ate my monkey and did up my buttons. Chickens and strange fish were brought out to the boat in pirogues paddled by spiked-haired women who opened Primus beer bottles with perfect teeth.

I was on a 22-day journey to Kinshasa from Kisangani, home of Joseph Conrad's fictional Kurtz, where the market could switch from peaceful to being like a single wild animal. A soot-coloured mass grave for 200,000 is witness to how apocalyptic these riots have been. One man, thinking I was Belgian, wanted to chop off my arms and legs with his panga. I explained that I was "un anglais, en vacances" to polite astonishment and then smiles.

Travelling 1,760km downriver in a country where the recent civil wars have killed 5.4 million people, I encountered an almost surreal optimism. "Monsieur Paul, we are happy! Happy!" The future is all in a land where there is no one much over 40.

The river is as strange as it is pretty. Bryan Ferry is worshipped. La Sape, short for the Society of Ambiencers and Persons of Elegance, began as a male style reaction in the capital to drab Belgian colonialism, and there is nothing less Belgian than Ferry. The harder it is to find a Comme des Garçons shirt, the more power it brings to the wearer. One leading sapeur, who took the name of Colonel Jagger, calls Bryan Ferry "my favourite Englishman".

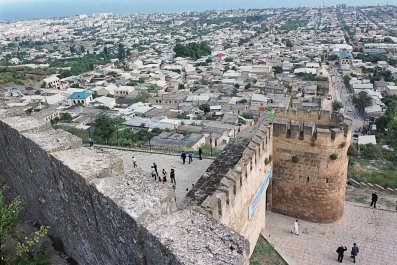

But Ferry's image travelled upriver and he was properly deified. At the sandy island village of Nganda Saisai I found his picture on a makeshift bamboo altar. The current members of the tribe, the Eleko, formerly cannibal, had not seen a white person in the flesh until I arrived.

At night they celebrated Bryan with rhythms from a 12ft drum and an incredible dance. They said Ferry was a "power" and worshipped even more on another tributary of the Congo. "He is a god," said the chief. Ferry's sons want to go out there.

At a nearby village, a less happy chief filled our boat with a cloud of biting, suffocating termites until we gave him our beer. "Could have been worse, could have been crocodiles," said the captain. Another elder's wife, Janine, killed in the war, had come back as a large pet crocodile. "Look," he told me, "she has the most beautiful eyelashes!" This man lived in a place where an old missionary map I saw had warned there were VERY WILD PEOPLE.