In 1770, a ship called The Endeavour made land in a lovely cove not yet called Botany Bay, observed by Gweagal men. Spears were waved on one side; shots fired on the other. An Aboriginal man was wounded. When the arrivals picked up the fleeing men's belongings, they found not weapons but fishing equipment. And so began the history of white Australia, soon to be spattered with such tragic communication failures like bloodstains on a beach.

Some of the artefacts retrieved by the first explorers found their way to the British Museum and are now on show in a landmark exhibition, Indigenous Australia: fragile, beautifully worked spearheads and painted shields that would have scotched the idea of ignorant savages scraping a living off indifferent land, for those who had eyes to see.

Today, 250 years after that first landing, Aboriginal art is still not widely understood by Westerners visually schooled in the Renaissance and Impressionism. In Melbourne, Den, an indigenous Queenslander, explains to me that for Aboriginal people, everything starts and ends with the land. He takes me through the beautiful Botanical Gardens, a dream of landscaped order amid what was wilderness in 1846 when they were planted. He shows me medicine plants and those with precious water in their roots, and tells me about the Dreamings, the founding stories of the Ancestors, the great beings whose actions created that land.

Each people has totemic Ancestors whose Dreamings they recite, enact and paint. In doing so, they learn their land, the routes through it and their duties upon it. In Western art, a landscape usually explains its subject; in Aboriginal art, the land explains the paintings. The dashes and circles are wind and contour and that eternal necessity, water. A painting is map and icon and more.

When land rights first became a topic of legal discussion in Australia in the 1970s, many Aboriginal people turned to art to explain their form of ownership. These paintings went to court, as a form of deposition in native title claims, and some of them succeeded.

Not before time. Cook and his cohorts had looked at the raw rocks and shivering gum trees and envisioned a promising site for a prison as wide as the horizons in terra nullius, or empty land. How those first explorers reconciled the artefacts they brought back with the notion of an unpeopled land is hard to grasp. When we struggle to spot the landscape features or Ancestral Beings amid the circles and dots of Aboriginal painting, it is worth remembering that they are not the only ones to have looked at Australia's ancient topography and seen things that others would say aren't there.

In the Museum of Victoria's Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre, I learn that selective seeing – or hearing – was a common failing. In 1835, John Batman persuaded the indigenous Kulin people to sign over large tracts of Victoria – according to him, anyway; they viewed it differently. The Crown scotched the plan, saying the land was Crown property (another version the Kulin might challenge) and the Treaty, now in England, is still disputed.

Batman, a megalomaniac who helped found Melbourne (he tried to call it Batmania) and "a rogue, thief, cheat and liar, a murderer of blacks and the vilest man I have ever known" according to his neighbour, is honoured with roads, gardens and statues all over Victoria. Near the imposing bulk of Parliament House, a statue of 19th-century poet Adam Lindsay Gordon bears strange praise: "He sang the first great songs these lands can claim to be their own." I think about the Aboriginal songs, thousands of years old, that Bruce Chatwin traced in his odd but compelling book The Songlines, and start to wonder if it is Aboriginal art that needs explaining, or the entire history of Australia.

Despite having astonishing rock etchings that predate France's Lascaux Caves paintings by more than 20,000 years, much of Australia's indigenous art was deliberately impermanent. Bodies were painted with ochre, drawings made in sand, and the traces removed once a ritual finished.

Most of what we call Aboriginal art is a modern solution to the desperate problem of communicating with an uncomprehending world.

In 1971, when Geoffrey Bardon started teaching art to children in Papunya, a squalid Northern Territory settlement full of displaced Pintupi people, the adults seized their chance, painting everything from canvas and brick to hubcaps and tiles

in an attempt to explain their "country" to the race that had claimed it for their own. Many of those paintings are now famous, their likenesses plastered over every tacky tourist tchotchke in Australia.

Yet the symbols and stories of the Dreamings – the keys to these maps of the Aboriginal world view – are still known by far too few of us. Chatwin observes that Aboriginal song is hard to appreciate because of the endless accumulation of detail, although he believes that even a superficial reader can glimpse a moral universe "in which the structures of kinship reach out to all living men, to all his fellow creatures, and to the rivers, the rocks and the trees". Like most of his book, this is probably partly true but also romantic and simplistic. Still, no populist work has tried to understand the art as Chatwin did the songs.

Not all Aboriginal art is so complicated. At the Bunjilaka Centre's First Peoples exhibition, intricate metal baskets hang in an eerily blue room: reimagined coolamons, vessels made from bark that traditionally hold newborn babies. The Empty Coolamons are indigenous artist Robyne Latham's eloquent memorial for the Stolen Generations: children taken from their parents in a deliberate attempt to absorb them into white Australian society. Perhaps, I think, admiring, regretting, we should avoid interpretation altogether. After all, these works are wordlessly beautiful – and as eloquent as a lament. "Aboriginal visual art," poet Les Murray has said, "is Australia's equivalent of jazz: a major new art style arising from the most oppressed group in our nation."

Still, though the Dreamtime may be as hard to explain as free jazz, context is vital if we are to understand. John Patten of the Bunjilaka centre puts it simply: "I don't like the name Dreamtime. I prefer just to call it history."

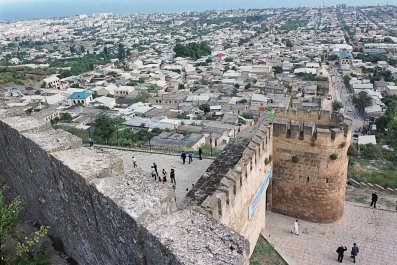

History without context is dangerous, or offensive. On Melbourne's Swanston Street, an extraordinary building has just been unveiled that has a grave face incorporated into its exterior. William Barak, a Wurundjeri Willum elder, successfully negotiated in 1863 for land to establish a farming community in northern Victoria. His settlement, Coranderrk, was self-sustaining until the inhabitants were thrown out two decades later; Barak led attempts at diplomacy, in vain.

His art, including Ceremony, a joyous portrait of his people celebrating the Dreamtime through the music and dance of a corroborree, is in the exhibition. It isn't hard to understand, either. However, you will learn nothing of Barak's story from his face on a building of premium flats – an odd place to honour a lifelong activist for indigenous land rights. Sixty kilometres away, his grave lies forgotten near a monument to the dead, in a sparse, peaceful cemetery that is all that remains of Coranderrk.

The drive back is gorgeous, through pine-green, fern-pelted valleys; it jars to re-enter the modern city. The dissonance is national but not necessarily eternal: perhaps this exhibition can help Australians to open their eyes and at last, 250 years on, find common ground.