ET Bureau

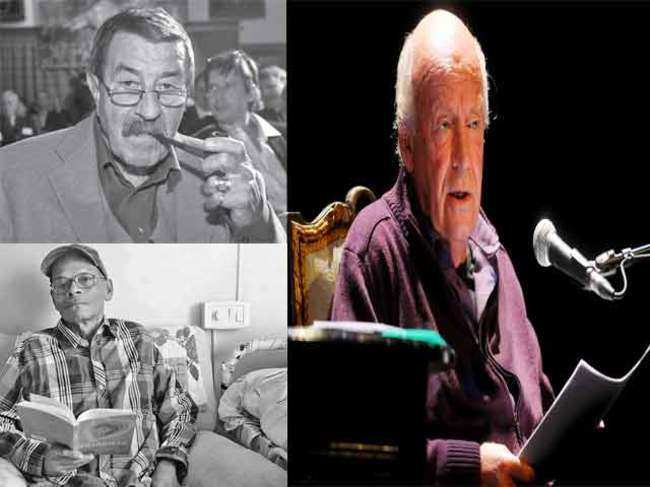

ET BureauThe week began badly for those who love writing and writers. On Monday, newsfeed choked on two deaths. First was Germany’s most famous contemporary writer, Günter Grass. Later in the day the foremost cartographer of the soul of Latin America too had crossed over. I put out a brief status update on my Facebook trying to quickly connect the two writers:

"Günter Grass and Eduardo Galeano die on the same day. It is interesting to contrast their approaches. Grass contracted Germany’s contemporary, mid-20th century history into The Tin Drum, and had to invent improbable realities. Galeano set himself the exact opposite job and retrieved his continent’s racial memory in a museum of mythical stories discredited and then nearly erased by centuries of colonialism."

The next day I got a text message of another death of a writer. "Vilas Sarang passed away." A dark blot of regret spread across the heart and mind instantly.

Only some months ago my teacher in college, Lalita Paranjape, had suggested we should go and see Sarang. He had been suffering for sometime. I never made that visit.

Each of these writers was distinct and distinctly reviled or ignored by their immediate worlds. Grass’ The Tin Drum, the first of his Danzig Trilogy, triggered an immediate nationalistic revulsion in 1959. Germany, already defensive for its defeat in World War II and its shameful Nazi history, was unable to forgive something that cut so close to its collective bone. The sheer, overvaulting ambition of storytelling that Grass had achieved in the book was overlooked or went unseen. The "immorality" of the book convinced the city of Bremen to revoke the prize it had bestowed on Grass.

Grass since then had been anointed Germany’s conscience. So long had that stuck to him that after his death a counterview was already in place. And predictably his critics pilloried Grass for his delayed confession of being part of the Nazi Germany’s deluded youth in his own callow days that he wrote about in Peeling the Onion.

"There are times when moral rigor is needed, but they pass. And yet Mr Grass was never able to move beyond them. Worse, he seemed to believe that, as the nation’s conscience, the rules he applied to others didn’t apply to him," wrote Jochen Bittner, the contributing opinion writer and a political editor for the weekly newspaper Die Zeit.

That is a risk all writers of a grand narrative will face. A resurgent moralism and the Marxist prism through which social reality was interpreted was already tiring Germany’s younger generation.

But Galeano, another purveyor of the grand narrative, did not pose such problems. One of the reasons was that he had a way broader canvas than Grass’ Germany.

His reclamation of South America’s suppressed history and its tryst with an almost Sisyphean curse of karmic poverty enforced by rulers was resonant across the continent. But the rulers hated it. His Open Veins of Latin America was banned by the dictators of the time, forcing many exiles for the author. When peacetime happened, a grateful people gave the savant his due.

But between these two major contemporary writers, where does one situate Vilas Sarang? Oddly, Sarang’s greatest strengths were his differences from them.

Sarang was minus ideology. The existentialist philosophers that Europe threw up in the wake of the First World War heavily influenced him such as Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. He was also a keen follower of the great stylists of the time: Franz Kafka and James Joyce and Jorge Luis Borges. One of the most quoted lines when referring to him is that Samuel Becket recommended him to his American publishers. But as theatre activist Ramu Ramanathan noted in his obituary to Sarang, "Critics in the Indian English press compare Sarang’s technique to Kafka’s imagery. This is a bit irksome."

Kafkaesque in Public Spaces Those who have read his Fair Tree of the Void would easily know the difference. Adil Jussawalla’s foreword explains the difference. Sarang Indianised Kafka in a very revolutionary way. He brought Kafka’s delirious, paranoid surrealism into the tropical, public spaces.

That is something Milan Kundera had credited to Salman Rushdie. Rushdie "tropicalized" London in Satanic Verses.

As Ajit Duara in his 2006 review of Sarang’s The Women in Cages notes: "Indeed, it is the stories set in Bombay, or Mumbai as he calls it with some distaste, that switch from George Orwell to Salvador Dali. In ‘A Revolt of the Gods’ the narrator is accompanying the Ganesh idol of his building society, perched on a handcart, as it is being taken for immersion to the sea. Suddenly the figure of Ganesh jumps off the handcart and sprints away, as do all the other Ganeshs in the serpentine queue. Any resistance from the public is met with a blow from the trunk of the God. People are convinced that it is a manifestation of divine wrath."

Sarang’s genius in seamlessly marrying his parent culture to the latest intellectual forefront of world literature went unheralded by India’s juvenile English press of the time. But a more hurtful thing was that his own Marathi world turned its back on his achievements. He was one of the celebrated stepchildren of the Marathi establishment; condemned for being less nationalistic when the Shiv Sena was rising in the state and parochialism became fashionable under an infantile form of guiltriddance.

This is particularly hurtful to Sarang who was a prize participant of the intellectual ferment in Marathi literature as part of the little magazine movement that swept the state in the ’60s.

As Duara notes: "Many of Vilas Sarang’s stories in this collection were written in Marathi. He has ‘redone’ them in English."

"Redone", as he explains, is different from translation because the stories are written a second time, without consulting the original, in order that they might work in the syntax of the English language. "The result is simply wonderful. The images and thoughts are local and the expression is in English. It is like watching a Federico Fellini film; documentation and fantasy in the pictures, Italian on the soundtrack, English sub-titles at the bottom of the frame."

I once asked him what he thought about magic realism. The laconic Sarang said, "It began when Gregor Samsa woke up as a beetle. The rest is journalism."

All original and significant writers share a tradition of cutting across national and notional boundaries, much like Grass, Galeano and Sarang. Sarang is a great writer whose backward place was where he was, as Nissim Ezekiel would have had it. As the country matures, his resurrection is imminent.

Get Unlimited Access to The Economic Times

Get Unlimited Access to The Economic Times