A lunchtime revel is being held at Terras da Costa, Portugal, a coastal shantytown of 500 people. Immigrants from Cape Verde, Angola and other former colonies of Portugal, as well as gypsy families, are serving each other cachupa, a bean stew, to celebrate the one-year anniversary of their new kitchen.

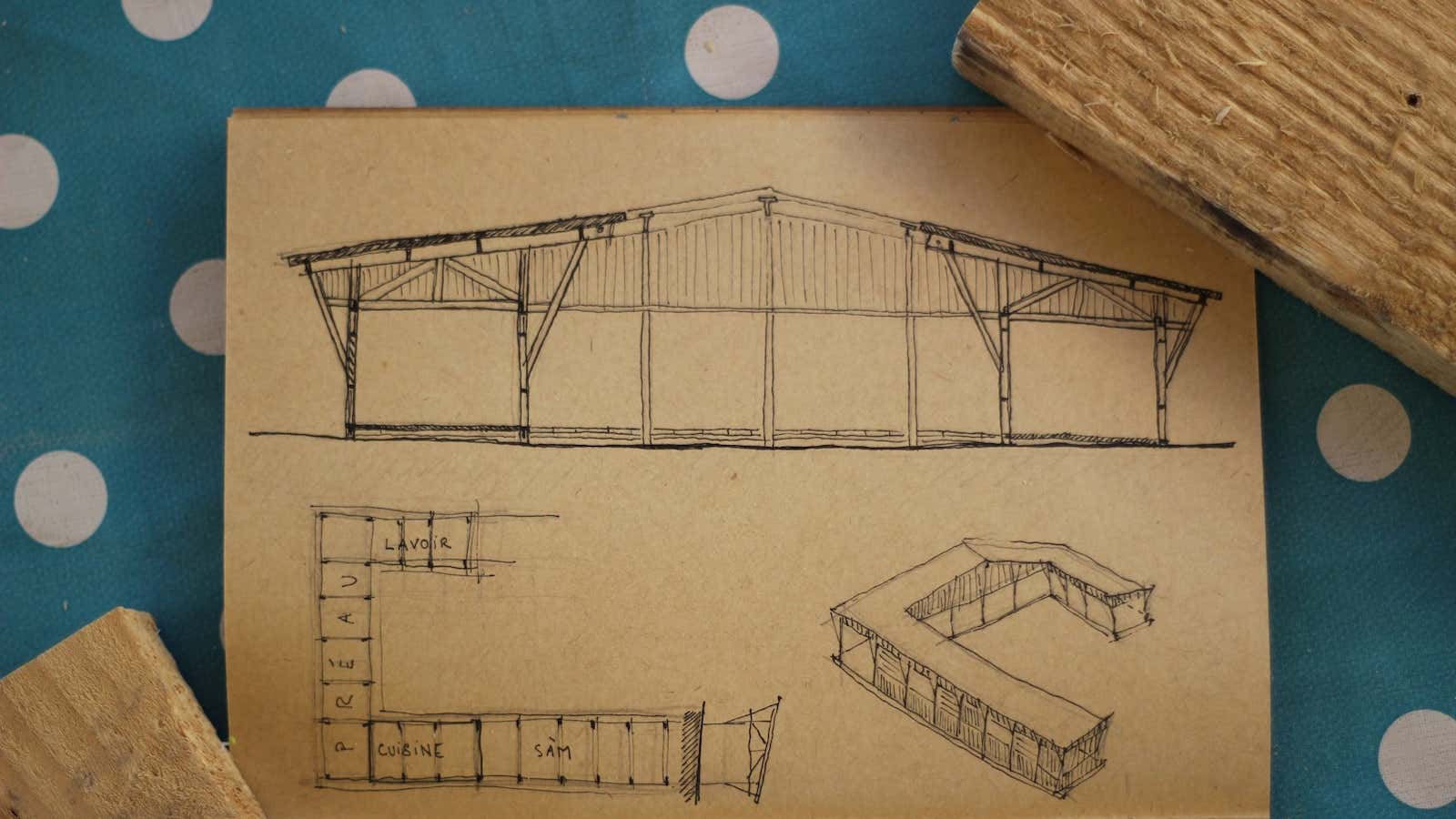

A wooden structure open on all sides, with spaces to eat, do laundry, grill and prepare food, the community kitchen has brought running water to the slum for the first time in thirty years. Built in 2014 by members of the shantytown in collaboration with two Lisbon-based architecture studios, this kitchen has since appeared in global architecture blogs and has triggered emotive speeches from local politicians, who helped the project get off the ground by circumventing laws against building on protected land.

Terras da Costa is a limbo zone of natural land where nothing can be officially built. Its inhabitants live in ramshackle homes, using salvaged materials and electricity stolen from the public grid. Illegal dumpers used to leave waste on the land here. People here come and go, looking for work in nearby Lisbon or emigrating to Spain and France with or without papers. They face high unemployment, social exclusion and other serious problems, and although most have applied for Almada municipality’s social housing, the waiting list is long. The idea of an architectural project here at first seems like bad taste.

The initial salvo in 2013 from architects Tiago Saraiva and Ricardo Morais—of ateliermob and Projeto Warehouse, respectively—to the Terras da Costa community was a flop. “I first came here with some students. We originally planned to redesign the football field, and to then organize a game between the community, the municipality and others,” Saraiva, 38, tells Quartz. “No one showed up.” But an elderly matriarch in the community, Dona Vitoria, gave the pair some advice: stay here, and build us a kitchen, so we have water.

“The problem of a lack of water is not an architectural one,” Saraiva says. “And we told them that. We also told them: we can’t work for free.”

But his team spent two years looking for funding, and eventually got a call back from the Gulbenkian foundation—a private local institution, museum and, increasingly, Portugal’s de facto NGO/cultural ministry. The Gulbenkian foundation offered a few thousand euros, enough to get started on a project to bring Terras da Costa fresh water. Importantly, Saraiva and Morais were also offered some wood from another community project a few miles away, that could be re-used for the construction.

Three years after the initial idea, the slum, formerly invisible to the outside world, is well-known. The new, U-shaped building has an impressive presence amid the dirt tracks, goats and corrugated iron surroundings.

Architectural photographer Fernando Guerra, who has works held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, has been commissioned to photograph the kitchen. A chief economics journalist from Reuters, reporting on Portugal’s financial crisis, has come to investigate the project, telling Saraiva he had not seen a slum like this elsewhere in Europe. Anthropologists and architects alike are coming to study the collaborative building process, as well as the impact on the people to whom this kitchen now belongs.

Anthropologist Ana Catarino, who is doing her post-doc at the University of Amsterdam, has been studying the kitchen project for several months. “I really like these kinds of projects,” she says, “but I am also suspicious of them. How do you define a community? You are more successful if you understand first where you are.”

Certainly, the new kitchen has not magically created order; if anything, it has done the opposite. “Before the kitchen, our sense of community was spectacular,” says Durval, a slum resident and one of the nine-member community commission that acts as a local governing body. Afterwards… it became a little bit confused.”

Durval is talking while walking down a “street” he hasn’t been through in many months because of family conflicts, heightened by some contested construction work on one of the nearby homes. Durval believes that the kitchen project—and the outside help and interest that came along with it—has helped. But more stability is needed from inside the community to sustain its impact.

“People are leaving, or too busy looking for work, or have too many other problems to engage with this in a dynamic way,” he says. Two keys are held by the neighborhood commission to the closed part of the kitchen, where food is prepared on a rotating basis. The lock has been broken once already.

Many in the slum don’t set foot in the place, preferring to stick to the makeshift bar Durval runs from his home.

“I don’t know if this kitchen could be used as a ‘model’”, Ricardo Morais, 27, says cautiously. “The main thing here was to bring water to the place—people were walking 1.5km to reach clean water before. But at least, the concept of people eating together is there.”

The penchant of architectural buffs to glorify sites where the architecture was not needed or asked for in the first place (take the world’s first vertical slum, created out of Caracas financial center Torre David in Venezuela) is an increasing interest in a world where the segregation of formal and informal, rich and poor, has reached dangerous levels. It’s also something that Morais and Saraiva hope to avoid.

“We want to avoid the idea of a touristic slum, like you see in Rio or São Paulo,” Saraiva says, adding that long-term involvement is the only way to engage in a project like this one. “Ricardo and I have to keep coming back to talk with people here. And if we don’t turn up for a month, Durval calls us to ask why. In the beginning we weren’t trusted, and I did feel that we were selling dreams that we couldn’t be sure to fulfill. Now, I think the people here trust us more than I would like them to.”

With local government now actively acknowledging the existence of this slum thanks to the kitchen project, and the new water tap part of the government budget for public facilities, a new and unconventional process has started in Terras da Costa. There are now requests for new facilities— a playground, a library—which have to be managed democratically.

There will be plenty of work ahead, and following through with it is what makes the Terras da Costa kitchen an unusually inclusive architectural project. “We wanted to break down the walls of invisibility here,” Saraiva says. “Now, there is a lot to do.”