- India

- International

In Sunita’s town, little has changed for gutkha

Shops selling pouches abound, outnumbering those who knew the face of the anti-tobacco campaign or her story.

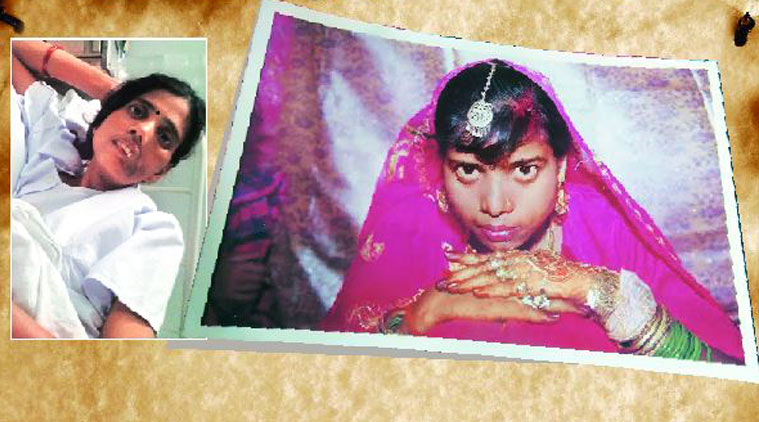

Sunita after her surgery for oral cancer, and as a bride.

Sunita after her surgery for oral cancer, and as a bride.

Sunita Tomar spent more than half of her life in the Bheemnagar locality of Bhind. Yet nobody here knows that the face of India’s anti-tobacco campaign lived, and died, in their midst.

An attractive bride when she came to Bheemnagar over 15 years ago, Sunita kept her face veiled like other married women around. When oral cancer consumed parts of it, she never ventured out without it.

In the last 22-odd months, Sunita would go out just for treatment, either to Gwalior about 75 km away or to Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital. She had stopped visiting relatives and kept to herself.

The only time she went somewhere else was to Delhi in August 2014, when the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the National Tobacco Control Mass Media Campaign that featured her 30-second testimonial in Hindi and English. Shot over three days in a guesthouse in Bandra, the documentary shows her face scarred by the cancer, but not her voice.

Sunita’s husband Brijendra Singh with their sons. (Source: Express photo by Milind Ghatwai)

Sunita’s husband Brijendra Singh with their sons. (Source: Express photo by Milind Ghatwai)

Her first trip to Tata Memorial was also her first time outside Madhya Pradesh. The youngest of three sisters and two brothers, Sunita grew up in Masuri village about 20 km from Bhind and did not study beyond Class V.

In contrast to Bheemnagar, it’s this village that saw her grow up that recognised her from the film. It’s also in Masuri, before she got married, that her addiction to tobacco may have begun.

None of her four siblings eats tobacco but cousin Dharmendra Singh Bhadoria, who has tongue cancer, says he had the same Rajshree brand of gutkha as her. The 38-year-old was operated upon in December 2012, a few months before Sunita’s tumour was detected, and has kept away from gutkha.

[related-post]

Sunita’s nephew Anil Singh would accompany Bhadoria for his treatment to Tata Memorial. That came in handy when Sunita developed a tumour in her left cheek. He isn’t surprised Sunita took to gutkha. “It is available everywhere,” he says.

Anita Jain, who was Sunita’s neighbour in Bhimnagar before the Tomars moved to a new home three years ago, is also from Masuri. She says like many women she knew, she began trying out small amounts of gutkha, before slowly graduating to two packets a day. In Bheemnagar, Jain runs a small grocery shop that also stocks gutkha.

She was among the first one to realise Sunita, or “Satto” as she called her, could be ill, when her younger son started frequenting the shop to buy Mango Bite toffee because it soothed her mouth ulcer.

“Even I have young children. I got scared when I got to know of her plight,” says the 41-year-old. So, four months ago, Jain says, she gave up gutkha. “I haven’t consumed a bit since.”

Sunita’s husband Brijendra Singh realised something was wrong when she started having difficulty swallowing food in June 2013. A local doctor told them her entire jaw would have to be removed and that the surgery would cost more than Rs 12 lakh. A month later, Sunita was admitted to Tata Memorial.

After the surgery in which her jaw and left cheek were removed, she was told she would be okay but there was always the risk of a relapse that could prove fatal. She lived in that fear till she fell ill again in March. As her condition worsened, she got herself discharged from Tata Memorial on March 28, wanting to spend her last days with her husband and children. On April 1, she died.

Singh, who supplements his low income from farming by taking up occasional driving jobs, says his life now revolves around sons Gandharv, 10, and Dhruv, 13.

He recalls that even when the disease was at its worst, Sunita would insist on doing everything for them. “She could hardly read and so she urged our sons to study regularly,” Singh says. Often, she would even feed them herself.

Her only wish was to see him get a regular job and to ensure good education for their sons, Singh adds.

Her death and the attention it got have made local politicians make a beeline for her house, with BJP MP Bhagirath Prasad assuring Singh that both his sons would be admitted to Kendriya Vidyalaya and not have to pay any fees. The talk in the neighbourhood is that Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself might visit the Tomars.

Singh, who holds a diploma in ayurveda, has also been promised a job at an ayurveda hospital.

Singh remembers how much persuasion it took for him to convince Sunita to take part in the campaign. “It was her previous looks, the fact that she was young and a mother of two that led to her being chosen as the face of the campaign,” he says. “But even otherwise she was shy and didn’t want to pose for the camera because of how she looked after the cancer.”

Part of the reason Sunita finally agreed was that she believed the documentary would make a difference.

In Bheemnagar though, there are few signs of that. Most grocery shopkeepers sell gutkha, displaying it prominently in their stalls. The onus lies with the government to regulate or stop the sale of tobacco products or their production, they say.

“What will we sell if we don’t sell gutkha pouches?” says Rajan Srivastava, who says it is the most popular item in his shop. Srivastava is among those who says he “had never heard of Sunita”.

“I didn’t see Sunita in person or on screen. All I know is it’s impossible to stop gutkha consumption if the pouches are available so easily,” adds Shrikrishna Rathod, who owns a shop not far from Sunita’s house.

Deepak Khatri, who also sells gutkha a few metres from Sunita’s house, even attended her funeral. He himself consumes a few pouches a day. “It’s difficult to get rid of tobacco addiction,” he says, as his father nods.

Dr Radheshyam Sharma, who was a Congress candidate in the Assembly elections, claims he has been organising a de-addiction campaign for two decades now, but he too had not heard of Sunita till her death.

There is another reason his wife’s untimely death at the age of 28 saddens Singh. She may have got famous for what she looked like, but he doesn’t have a single photograph of her with him and the children, he says. “We never felt the need for it.”

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05