Perhaps we are too civilised

Joram Nyathi Spectrum

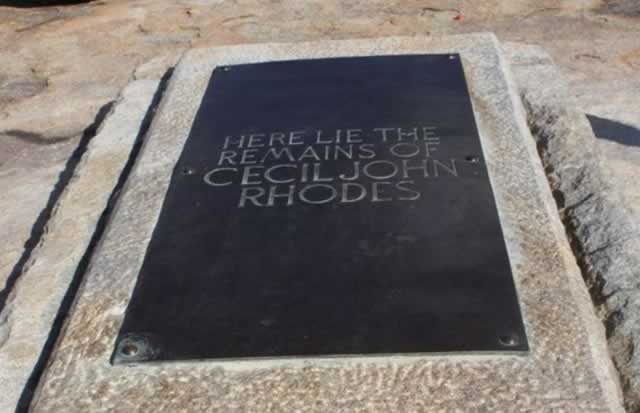

Rhodes’ grave hewn into the granite rock of Malinda Ndzimu hill in the Matopos represents a permanent scar which even the whiteman’s money cannot heal

PERHAPS we are too civilised in Zimbabwe. The whole black-on-black violence which has dogged our politics since 2000 has centred around either asserting our rights as free Zimbabweans or defending foreign property rights. It has been about asserting our sovereignty or staying subservient, remaining slaves or restoring the dignity of the African people.

That violence has been about redefining the meaning of independence for a former colonised people.

That redefinition began with a symbolic, or political, transition from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe. Soon we shall be 35 years.

But the ghost of Rhodesia still haunts our land with its unyielding immanence, in its progenitor Cecil John Rhodes.

In civilized America the white police shoot to kill black suspects. Civilized American white soldiers didn’t hesitate to topple the statue of former Iraq president Saddam Hussein. The evil triumvirate of France, Britain and America had no qualms about overseeing the desecration of the body of their slain victim, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, and ensuring his remains were thrown into an unmarked grave in the desert.

It was a brazen effort to obliterate the memory of one of the few African leaders who wanted to restore to Africa its dignity, a man who strove to give his people a lifestyle far better than some European states, a man who challenged European hegemony by asserting true African independence by giving the continent its own currency and do away with the US dollar.

He soon became a threat to white interests and had to go, with the indignity of his mangled body dragged through the streets by howling “democrats” bringing Libyans American freedom, liberty and fraternity. He was reduced to a common law criminal. And today ‘’democracy’’ flourishes as much as oil outflows from Libya’s belly whose surface is surfeit with blood!

In barbaric Zimbabwe monsters like Rhodes are feared in their life time for their cruelty against blacks; in death they are revered for their white, historical significance. He declared that he preferred land to kaffirs.

And for the first time in about 20 years President Mugabe gets some positive coverage in the virulently anti-black South African and Western media even as he “steals the show” locally for speaking too much, never mind the substance of his statesman’s speech, all delivered with the eloquence of a 40-year old, and off-the cuff.

Those are the bitter sweet ironies of Africa. Baffling ironies given that the “Rhodes Must Fall” spirit sweeping across South Africa today bears the hallmarks of President Mugabe’s relentless campaign against colonialism and its imperial relics. A man of a lesser intellect in search of a publicity stunt would have played to the gallery on the Rhodes issue, given the high platform President Mugabe occupied at Union Buildings in South Africa on Wednesday.

Instead, this is what we got: “Rhodes was a strange man that South Africa forwarded to us when he was a corpse . . . We have his corpse, you have his statue. What do you want us to do with him? Dig him up? Perhaps his spirit might rise again and we will not know what to do with it. We cannot tell you what to do with the statue but we and my people feel we need to leave him down there.”

Nothing has excited the Whiteman’s wrath against Mugabe more than his campaign for Africans to take control of their natural resources, his efforts to empower the African people.

For that, he has been likened to Hitler, called the anti-Christ and judged the most suitable candidate for The Hague for alleged human rights violations and crimes against humanity. It is a public verdict the white world would love to see confirmed in their courts. This Mugabe, who says Rhodes’ bleached and ashen remains should be allowed permanent stay at Matopos Hills, the desecrated spiritual heartland of Zimbabwe.

His consummate political skill left those among the audience who were itching for slips of the tongue so they could write headlines like “Mugabe Must Fall” were completely disarmed. The rest of what he said about Tony Blair and the 51/49 indigenisation lost its sting once he assured the white world that Zimbabwe was a willing host to Rhodes’ corpse.

President Mugabe’s words were deliberately calculated. Isn’t it a bitter irony that the spiritual revolt against white arrogance and their profane images should first run riot in a land which hitherto had seemed so placid, so content to live with beloved Nelson Mandela’s apartheid legacy, complete with its gross and profound racial inequalities?

Shouldn’t that fire have emanated from Zimbabwe alongside Mugabe’s loathed land reform?

So Mugabe reasoned; why stoke a rampage already underway in a gracious neighbour’s yard?

The rampaging youths might have felt let down, but Mugabe can’t be blamed for recklessness, for adding fuel to his host’s smoldering fire. An unsettling question then invites itself: is our generation of Zimbabweans worthy inheritors of Mugabe’s liberation legacy?

Mugabe and his generation have fought and won the political and economic battles. But those victories can easily slip away, be overturned, be lost, without a truly Zimbabwean spirit of who we are and what it means to be Zimbabwean. That is a spiritual matter going far beyond birth and citizenship. It is the essence of being and belonging even when in foreign lands.

Rhodes’ grave hewn into the granite rock of Malinda Ndzimu hill in the Matopos represents a permanent scar which even the whiteman’s money cannot heal. The drilling of that granite rock was a desecration of our sacred, spiritual heartland, an attack on our worldview, and set our spirits roaming in the wilderness in search of a home.

Are they reconciled to share their home with Rhodes forever in an independent Zimbabwe? Is it not probable that the Ndebele indunas’ “Bayethe” to preserving Rhodes’ remains in perpetuity was the capitulation of a conquered people? If malinda ndzimu means, according to retired journalist and advocate of the Rhodes Must Stay school Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu, “keepers of god”, or, according to my interpretation, “home of the spirits”, whose god or spirit were the Kalanga elders talking about? A white god? Is there no meaning in symbolism?

Without a spiritual anchor, we are like wondering souls even as we proclaim to be free, to have repossessed our land and control our natural resources. We remain forever enamoured of Rhodes, drifting almost like in a dream, fatally attracted to his ghost, searching across the oceans all the way to England.

Perhaps we are too civilised a generation, too decent, or alternatively, too obtuse to embrace, to give honour to our own prophet. It took war veterans to heed the message to take on the whiteman ensconced on commercial farms. Now it has taken youths to confront the whiteman and his symbols in a free South Africa, yet the source of the message has stayed the same.

Comments