Raheem Sterling rejecting €140,000 a week is obscene - but at least he's honest

Liverpool winger has become a poster-boy for excess in his hard-ball stance over contract talks, but he simply playing by football's modern rules

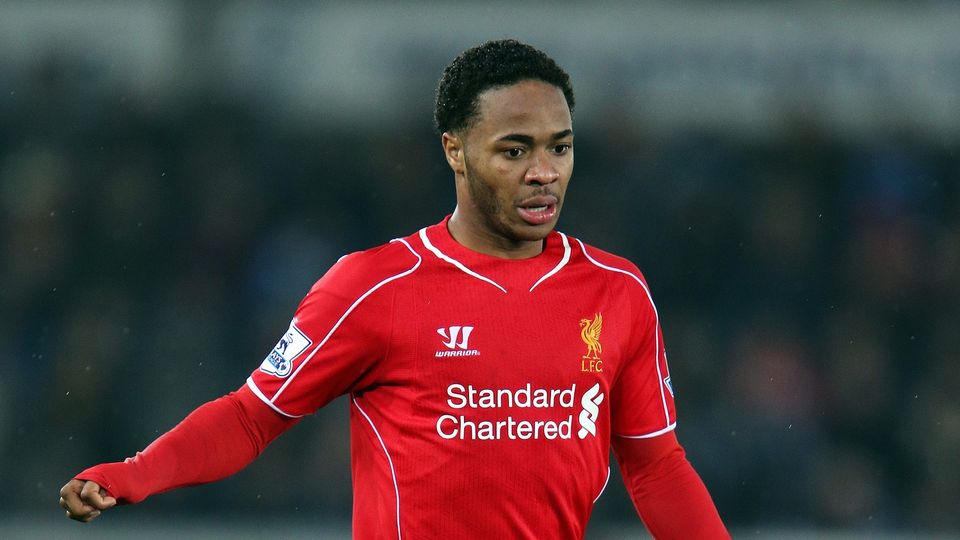

Raheem Sterling

Sometime in 1999, a journalist relatively new to a sports reporting career was granted a thorough education into the fantastical financial perspectives of a professional footballer.

He found himself discussing salaries with a top class player and decided to have a bit of a moan.

“I only earn £12,500,” was the complaint.

There was a pause.

“Is that a week or a month?” was the player’s response.

The reporter waited for the giggle, but it was a straight face staring back.

The realisation that some (not all) footballers have no concept of the value of a pound - believing we all measure pay slips in thousands over a week rather than a year - was both amusing and disillusioning. The empathy gap has been widening ever since.

To those of us accommodated in that distant dwelling from training grounds we like to call ‘reality’, many footballers and agents inhabit the kind of world Terry Pratchett would have been proud to call his own. Egos clash if players have the audacity to reject offers that will only make them a mega millionaire when it is quite evident they have their heart set on being multi-mega millionaires. We become so accustomed to seeing numbers between £80,000 and £200,000 a week in the Premier League, rarely is there a moment to pause, digest and consider its grotesqueness, judgment invariably passed based on popularity.

Raheem Sterling will not resolve his future until the summer

“Have you seen his recent goals or assist record? He deserves every penny he gets,” is a regular justification.

“He wants how much? He can’t even take a penalty,” the counter-argument.

Every so often someone like Raheem Sterling comes along to become the poster boy for these economic excesses, even though using him and his stance over a new contract at Liverpool as the basis for a diatribe against players’ wages would be too easy, and also unfair. Sterling is no more than a product of the age, and for football to rail against him is rather like Victor Frankenstein holding head in hands as his creation develops free will.

Footballers have a talent with a value placed upon it and a short career, so good luck to all of them if they can manipulate an industry created to facilitate such exploitation. It’s hideous, of course, but that’s capitalism, kids. The entertainment business pays well.

Clubs treat some players shabbily, but those in demand have the expertise to maximise their worth. Talent is power is money in all the most popular sports, and the political battle between clubs, players, managers, agents, leagues and governing bodies to protect and enhance their own interests, position and wealth is ceaseless.

Liverpool have little to fear from the Sterling situation, other than the small detail of losing the player, which they’ll easily get over if it comes to that. They’ve lost better in the last 12 months, never mind in their history, and every wage bill has its ceiling.

Raheem Sterling, pictured, was hailed as a 'great learner' by his Liverpool boss Brendan Rodgers

The Anfield board knows there will be a popular movement in their favour as the figure Sterling rejected (an obscene £100,000 a week) and is demanding (an even more obscene £150,000 a week) is dissected in public. If Sterling is sold for £40 million this summer, it is more likely to provoke a bit of disappointment and ‘ho-hum’ than a fans protest. There was a noticeably impatient murmur whenever Sterling lost possession against Manchester United on Sunday. Presumably he knows why.

Sterling and his agent Aidy Ward will have their sympathisers, but broadly speaking the pounding in the PR war has started, while Fenway Sport Group’s hard-line stance will be presented as an ‘example’ to others.

If every promising 20-year-old is valued according to what his agent wants, that new TV deal will be absorbed within one round of contract extensions - and we can’t have that when there are so many middle managers doing the square root of absolutely nothing in need of subsidising at Premier League clubs these days.

As we lay it on the player there should be a note of caution, however. Liverpool, lest we forget, bought into this when they invested so heavily in Sterling as a 15-year-old and there should be no surprises at what has come to pass - the biters are being bitten.

When Liverpool signed Sterling five years ago they knew what they were getting on and off the pitch. He was taken from the QPR Academy by the highest bidder, the big club removing the crown jewels from a smaller one. He chose Liverpool because they paid more than anyone else, not because they had any recent track record blooding youngsters.

What is happening now is on a grander, higher profile scale where Ward is exploiting interest from elsewhere to provoke Liverpool into paying more money. Are Liverpool really surprised the kid who wanted to be the highest paid 15-year-old in English football, and then wanted to be the highest paid 18-year-old in English football, now wants to be the highest paid 20-year-old in English football? Blaming Sterling for behaving exactly as he did when he left QPR is hypocrisy. Those who knew Sterling and his representatives at Loftus Road must be granting themselves a wry smile.

True, the deal in 2010 was completed before FSG’s takeover and well before Brendan Rodgers was manager. We’ll never know if John W. Henry would have sanctioned it like Tom Hicks and George Gillett. At Rodgers’ behest, recent changes at Academy level at Anfield are shifting the onus firmly onto self-development rather than plucking players from elsewhere, but there must be acknowledgement the most successful recent graduates from the youth team – Sterling and Jordon Ibe – were products of a now abandoned policy.

In defence of those who signed them, Liverpool have gone so long since producing a world class player from the locality (Steven Gerrard in 1998) they felt they had to act by looking beyond The Mersey and for the last three seasons Sterling has been presented as if he is one of Liverpool’s own, the current regime quite happy to assume credit for Sterling when it suits.

On the walls of Liverpool’s Academy there is a photographic display celebrating all those who came through the club’s youth ranks and Sterling’s portrait rests alongside that of the local boys Robbie Fowler, Gerrard, Michael Owen, Jamie Carragher, Steve McManaman and the rest.

Given Sterling was spotted and nurtured by others, at best his place does not sit comfortably and to be blunt it should not be there at all.

The current situation exposes the difference between players shaped by their club – and in the case of Liverpool the working class community in which they were raised - and teenagers lured with the promise of millions. It’s the price you pay by spending so much on youth players in the first place.

Anfield history shows it is much easier to take advantage of the loyalty and connection of the local players to their badge to keep their salaries at a manageable level throughout their career – a fine line often tread between incremental rewarding and taking advantage. All clubs are the same. When they say the onus should be on developing their Academy, the consideration is financial as much as one of identity.

Contrast Sterling with 21-year-old Harry Kane, brought through the ranks at Tottenham Hotspur and recently rewarded with a £45,000 a week deal, incomparable to that requested by Sterling. Is one such a more exciting prospect than the other?

The products of Liverpool’s Academy ‘Golden Age’ under Steve Heighway between 1993-1999 had to wait until their mid to late 20s to get anywhere near parity with the club’s highest earners, and with the greatest respect most were better players than Sterling at the same point in their careers.

That’s the fundamental image problem Sterling has as phrases such as ‘going rate’ and ‘market value’ are sprinkled liberally into the justification for his position. No-one at Anfield – in the stands as much as on the board – really thinks he is worth it.

Sterling is a good player, a very good player, but the problem for him and his advisor is this.

He is not (yet) great.

He is not Robbie Fowler aged 17 great.

He is not Michael Owen aged 18 great.

He is not Steven Gerrard aged 19 great, or Steve McManaman aged 20 great.

He is not Jamie Carragher in Istanbul great (if you were assessing wages ahead of the 2005 Champions League Final, Carragher would have come in above Dijimi Traore but well below Harry Kewell and Djibril Cisse).

Many of those players can argue they were undervalued as they saw expensive recruits move to Merseyside who were paid double what they were commanding, the club calculating the players’ love of Liverpool and the stature of the club would keep them more than salaries.

Those who called the bluff like McManaman, who only matched talent and wages by moving to Real Madrid in 1999, had to suffer the predictable ‘greed’ taunts before he left, even though history has shown that criticism was unjust.

Even the millions Gerrard turned down when he was offered massive pay rises to leave Anfield were deemed inconsequential once his Liverpool critics deemed him no longer value for money in his mid-30s.

“This is business,” is a common, logical explanation when a sober position is demanded from the club. There is often an absence of such rationality when players adopt the same position and have the audacity to threaten to leave.

Sterling is not yet worth £150,000, £140,000, £130,000 or even £100,000 a week, but for all that there is something admirable in the manner he and Ward view Liverpool as mere employers, ignoring the guff about ‘loyalty’ that so often pollutes these matters.

Their detachment from any emotional pull to Anfield has enabled them to dismiss as irrelevant the tsunami of criticism that is coming their way if no deal is struck, Ward is presumably revelling in the image of himself as the Hooded Claw presenting his terms to the Anfield board.

He must also have convinced Sterling the likelihood he’ll be made a scapegoat for every poor Liverpool display – as against Manchester United – is a price worth paying for the long-term goal. That might be brave or daft, but it’s certainly new territory for Liverpool when discussing terms with a 20-year-old.

Whatever the outcome, the cold, professional approach to the negotiation is to be welcomed for the insight into the mind-set of some modern players, which is so often disguised whenever contract extensions are under discussion. This is so much more candid than those disingenuous statements we’re expected to swallow whenever deals are extended – the equivalent of inviting your fanbase to applaud a millionaire’s pay rise. Some deals are penned to expedite a transfer six months later – see Luis Suarez last season for more details.

In a different time and place, Sterling would have signed the first offer of £80,000 a week before Christmas and the club would have released a statement about how the (then) teenager has become part of Anfield kin and never gave any hint he wanted to play for anyone else.

There is a perverse sense of pleasure we’ve been spared the usual insincerity, the only blip when Sterling was asked to speak prior to Liverpool’s Europa League with Besiktas and implied there was no better place than Anfield for a young player. A carefully worded response on his behalf would not have been so clumsy.

You can call Sterling greedy or poorly advised or ungrateful or arrogant or naïve or overrated as much as you wish – and supporters are evidently going be more intolerant of poor performances - but the one thing you can’t call him through all this is dishonest.

Sterling and his agent are guilty of no more than exposing what top-level football clubs hate most: the unpalatable truth that for the majority of footballers, managers and board members, commitment to their ‘family’ club is no more than a business arrangement to be renegotiated every two years.