Scientists are looking for -- and finding -- little bits of plastic in a lot of places lately: ice cores, deep sea sediments, coral reefs, crab gills, the digestive system of mussels, even German beer. Now, new research suggests they need not actually be searching for the man-made material to discover it.

"We never thought of looking for plastic," said Javier Gomez Fernandez, a biologist at Singapore University of Technology and Design.

His team's accidental finding of plastic in the skin of both farmed and wild fish, published online this month in the supplementary section of their unrelated peer-reviewed paper, adds to already growing environmental and public health concerns about the plastic particles pervading our oceans and waterways.

Over time, waves and sunlight break down large chunks of plastic, leaving the remnants of discarded packaging, bottles and bags nearly invisible to the naked eye. These so-called microplastics, particles under a millimeter across, may pose big troubles, experts warn.

"It fragments quickly. We fear that as plastic continues to break down, it becomes even more susceptible to being eaten by marine organisms or taken into the gills of fish or, apparently, even embedded into their scales," said Kara Lavender Law, of the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Plastic has been found in creatures ranging from worms and barnacles to seabirds and marine mammals, Law noted. Synthetic chemicals can then travel up the food chain, and potentially on to our dinner plates.

Law co-authored a study published in February that estimated 5 to 13 million metric tons of plastic litter enters the world's oceans every year. That's equivalent to five plastic grocery bags filled with plastics for every foot of coastline.

Since plastic does not biodegrade, it simply accumulates -- year after year.

Only about 1 percent of the plastic estimated to reside in the oceans has been accounted for by the five major floating garbage patches, according to another study published last year.

How all this translates into potential harm to wildlife or human health remains unclear. Law and other experts, however, suggest the outlook isn't good. Some plastics are manufactured with chemicals known to mess with hormones. Perhaps even more concerning is that plastic can act as a sponge for other toxic pollutants such as flame retardants and pesticides. Even DDT, long banned in the U.S., still lingers in coastal waters and can hitch a ride on plastic particles.

Decades of convenient plastics and environmental pollution "may be coming back to haunt us in our seafood," said Chelsea Rochman, a postdoctoral fellow in conservation research at the University of California, Davis.

At the forefront of the current debate over microplastics are microbeads, the minuscule balls of petrochemical-derived plastic added to hundreds of cosmetics, sunscreens, toothpastes and exfoliating body washes. When they're rinsed down the drain, microbeads can flow through sewer systems -- where they are often too tiny to be efficiently filtered by wastewater treatment plants -- and into lakes, rivers and, ultimately, oceans. They arrive in the environment already fish-food size, even before the waves and sun begin breaking them down.

More than a dozen states have begun addressing the emerging concern. Microplastic pollution in the Great Lakes drove Illinois to pass the first ban on microbeads last summer. A policy brief from the Society for Conservation Biology, authored by Rochman and several other microplastic experts, is set to be sent this week to senators drafting similar federal and state legislation. Rochman said she anticipates signatures from about 50 scientists on the brief, which supports the bans and warns of potential loopholes in the Illinois bill that could allow for continued production and use of microbeads.

Meanwhile, Rochman called the fish skin finding "unexpected" and "interesting," and noted that it "opens up new questions."

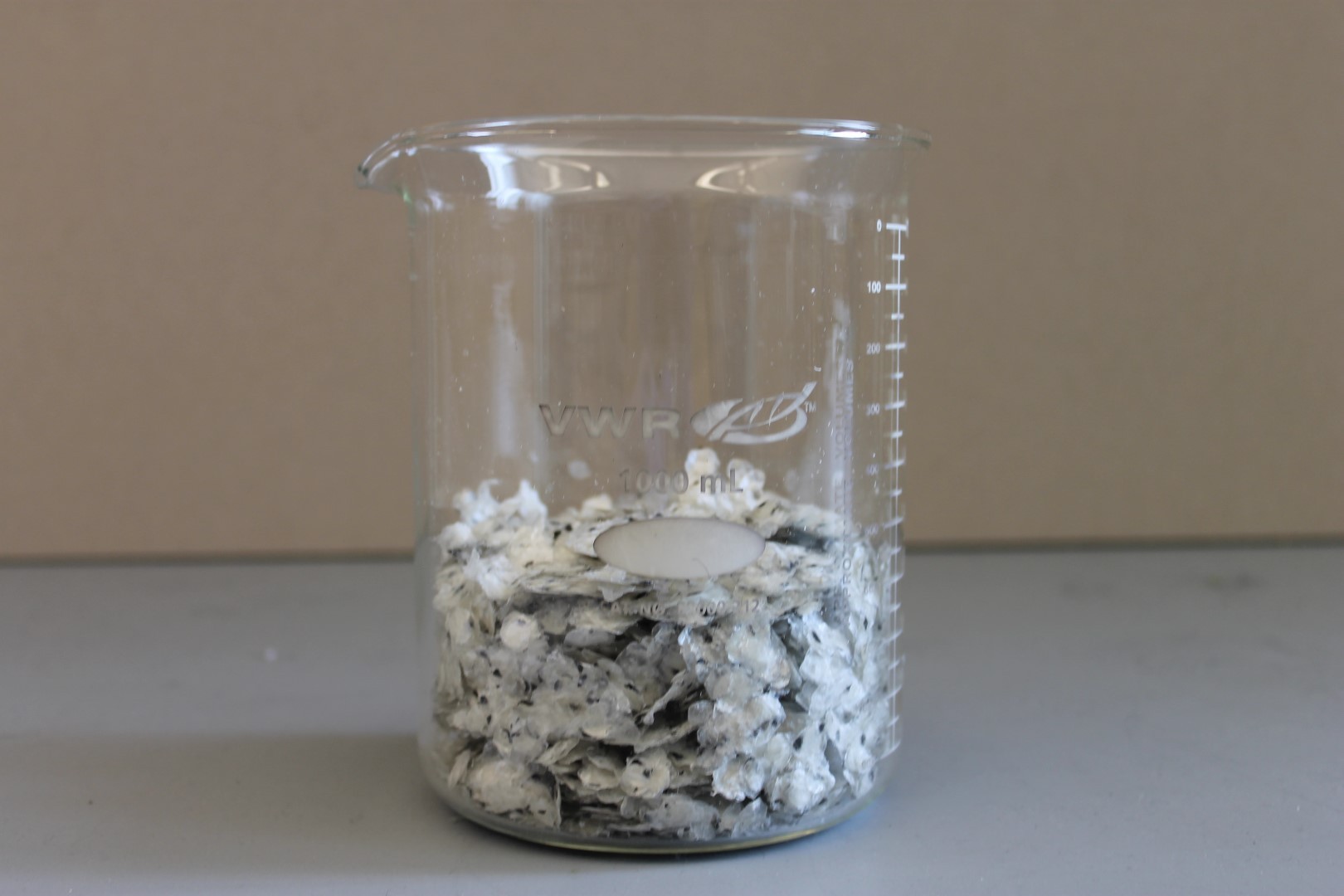

The discovery began with a one-liter bucket of slimy fish scales and skin. "It is smelly," said Fernandez, of working with the "fish soup" that filled the bucket. "Fortunately, I come from a region of fishermen [Cantabria, Spain], so I kind of like the smell of the sea."

Fernandez and his colleagues from Harvard University and the University of Washington had been investigating the presence of a natural substance called chitin when they also began detecting a foreign material in the farmed Atlantic salmon, and wild haddock and carp. To their surprise, the little particles entrapped in the filmy fish skin -- averaging about one-tenth the width of a pinhead (0.1 millimeters) -- turned out to be various types of plastic, including polystyrene, or Styrofoam.

"There is an absolute lack of knowledge on the impact of plastic at that scale or even where it goes," said Fernandez. "We have found that when it is small enough it acquires the ability to be entrapped in the mucosa of marine animals."

"We don't know the extent of this process, or if it happens in other animals. But it definitely points to the need of evaluating this issue in more detail," he added, noting that humans have mucosa in the digestive tract.

The connection may not be farfetched, according to other experts. For one thing, fish skin is coated in mucosa. For another, human mucosa has shown an affinity for plastic: Researchers have long used small plastic balls to mimic viruses when studying the virus-trapping ability of mucosa in the human cervix and digestive tract.

Andrew Watts, an expert on ocean plastic at the University of Exeter, in England, led research published last June that found plastic in the gills of crab.

"We know crab gills are coated with a thin layer of mucous," Watts told The Huffington Post in an email.

More research is needed to be certain of the source of the plastic found in the fish skin. While Fernandez noted that his team was extremely careful to avoid any potential contamination during their work in the lab, they can't rule it out. Fish are also often caught with plastic nets, and transported in polystyrene boxes, noted Watts.

Watts pointed out that he always washes fish before he cooks it, although he added that this may or may not remove the plastic, depending on its location within the skin.

"There are a whole host of questions that could come out of this," said Law. "We're starting to ask more questions about our drinking water."

"And we're really just looking at the tip of the iceberg in terms of effects," she added.

The most pressing need right now, according to Law, is to improve waste management systems so that they can properly capture the plastic. She and other experts added that consumers can also do their part by choosing reusable shopping bags and avoiding the purchase of heavily packaged products or personal care products with "polyethylene" listed on the ingredient list.

"In the long-term, we all need to think about how we're using plastic," Law said. "Individual actions can add up to have a positive impact."