"SUPERMAN KILLS SELF" ran the headline in June 1959, when George Reeves, star of TV's long-running Adventures of Superman was found dead of a single gunshot wound. Conspiracy theories have since argued that he was the victim of an accidental shooting, or it was murder (his girlfriend had mob connections), but for kids at the time the impact was devastating.

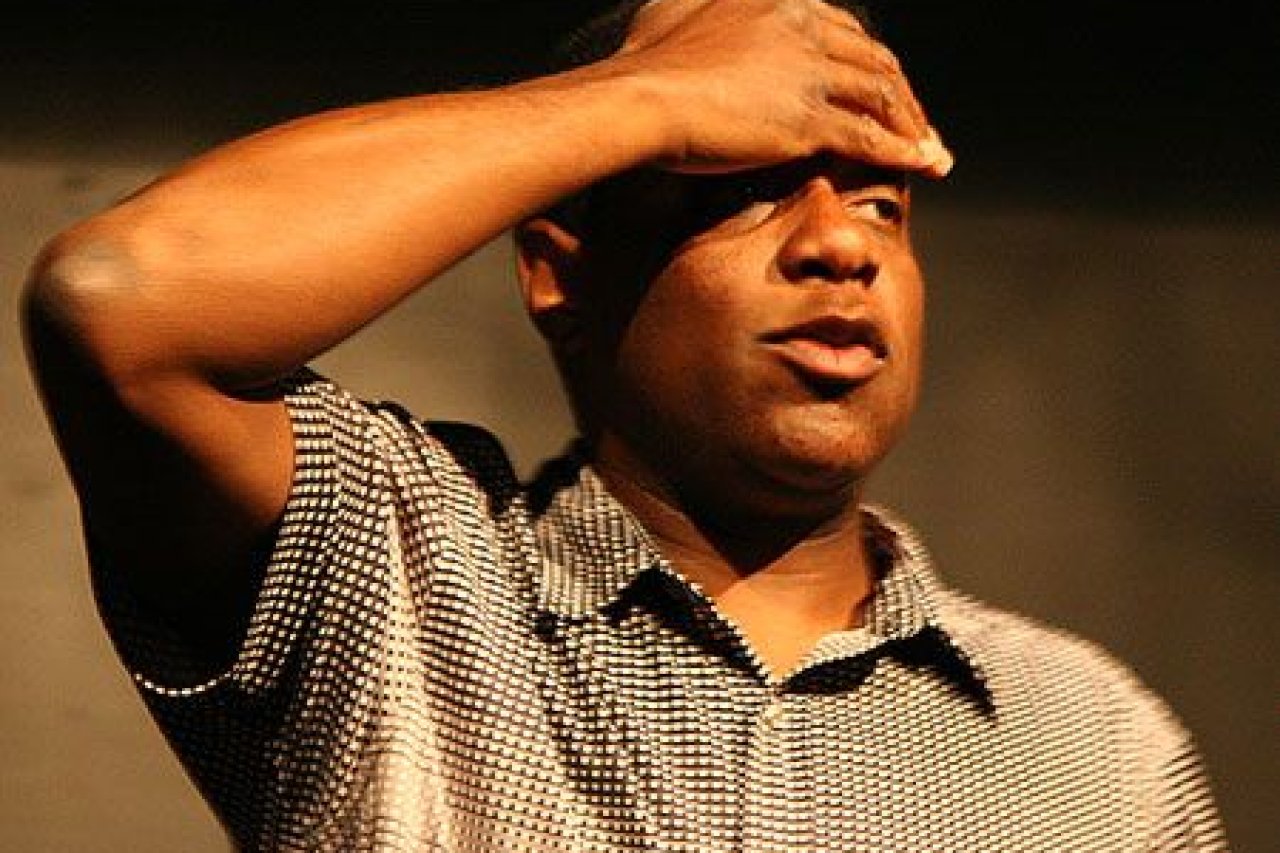

"It was national news," says stand-up comedian and radio host Brian Copeland. "One guy [in a documentary] said he went to school the next day and it was like the land of the zombies. Everyone was walking around just in shock."

Copeland was 10 when he found out, in 1974, about Reeves's demise. "They say he was a father to two generations; we all watched that show in reruns, and we couldn't believe he would do that." Copeland was a black child living in the predominantly white (99.4 percent according to the U.S. Census) Bay Area suburb of San Leandro, California. He coped by spending most of his time in his room, reading comic books. "When I was a kid, Superboy was my best friend," he recalls. "He was isolated, I was isolated; he was the only one of his kind, I was the only one of my kind."

That sort of thinking is common to most kids who identify with superheroes (If only you could see my magical powers!); it's also the way most people with depression feel, unique and invisible—whether they want to be or not.

Were it not for the national state of denial over Reeves's death, his suicide could have been a teachable moment, as they say, the beginning of a dialogue about depression and its toll. Copeland was one of those who refused to believe it, though now, at age 50, having attempted suicide and having written and performed a one-man show about his experience (The Waiting Period, at San Francisco's Marsh through April 19), the evidence seems overwhelming. "His blood alcohol was 2.0," says Copeland, "he'd had all these bad breaks, he was coming up on a bad marriage, his career was going nowhere. And in that one moment, because that gun was there, he said, 'Fuck it.' That's exactly what happened."

Copeland was diagnosed with depression in 1999 though the 10 days dramatized inThe Waiting Period occurred in 2008. (The title refers to the period of time one must wait in California to be able to buy a gun, the method of dispatch the comedian had chosen.) "Just a series of calamities," is what he recalls about his decision to kill himself. "My grandmother who raised me died suddenly; my wife took off; I got into a car accident that almost left me quadriplegic, I had to have surgery that left me in a neck brace, immobile, for three months; and I was just severely depressed."

He was also taking care of his three teenage children, from whom he tried to hide the depths of his despair. His daughter, Carolyn, is one of the more touching characters in the show, zeroing in on her father's telltale traits when he became too depressed to be a responsible parent (Chinese takeout turned out to be one warning sign). She had been one of his biggest boosters for her father's first one-man show, Not a Genuine Black Man, about Copeland's experiences growing up in San Leandro. (The longest running one-man show in Bay Area theater history went on to New York and has since been adapted as a book and TV pilot.) But like her siblings, she has only seen The Waiting Period once.

"All three kids came opening night and they would not come back," says Copeland about a show that prompts as many laughs as tears. "They knew what it was for, and about; they said, 'Dad, we lived it.'"

The play had its genesis in the earlier work, in which the adult Copeland comes to terms with the casual racism he endured as a child (being stopped by white police for carrying a baseball bat or riding as a passenger in a white woman's car). "This stuff starts to come up and I don't understand why I'm breaking out crying for no reason," he says. "This ended up with me in a garage with the motor running." Longtime San Francisco Chronicle theater critic Robert Hurwitt was among those who thought the depression angle was glossed over in Genuine, and Copeland began to contemplate giving the subject more attention in his follow-up piece. "My director and collaborator David Ford and I got together and talked about it a little bit," Copeland recalls. "Then I heard about the suicide of a 15-year-old kid—a kid I never met, [though] his cousin and aunt and uncle are very dear friends of mine.… One day he sent out five texts saying 'I love you' and then lay down on the railroad tracks.… When I heard that I said, 'I'm gonna tell my story and maybe it will help some people.'"

The Waiting Period opened in 2012 to rave reviews. "The show ran for a year and a half, and I had to stop it," says Copeland. "In order for me to convey to the audiences what it's really like to be in that place, I have to go there on stage, and after a year and a half I couldn't do it. It started to suck me back in." He performed the play at colleges and spoke at high schools (one of The Waiting Period's most poignant moments comes when a peppy girl at an affluent high school—"like Kelly Ripa on steroids"—outs herself as a fellow sufferer after hearing him speak) while developing other projects and continuing with his myriad day jobs. (Copeland is a recognizable figure in local media, having hosted the local Fox and ABC affiliates' TV talk shows, as well as his own radio program on KGO radio.)

"What really made me decide to bring it back was Robin Williams," Copeland says of the comic who committed suicide in August 2014. "I knew Robin; we were not great friends, but coming up in comedy in the Bay Area you had to know Robin. Last time I saw him he asked if I had DVDs of The Waiting Period and Genuine; he'd never seen either show. I have low-quality DVDs of both, archival things, so I sent them to him. I don't know to this day if he ever saw them."

Today Copeland dedicates his performances to different victims of suicide; the night I attended the program contained a picture of Matthew Potthast (February 2, 1996-January 20, 2015), who shot himself while his mother was in the other room. In the photo his mother provided he is wearing a tuxedo and smiling, no sign of despair behind his glasses.

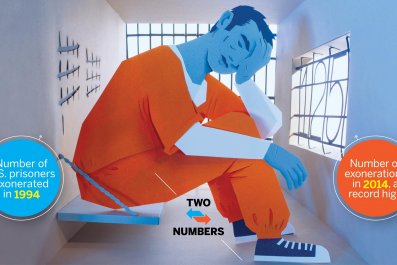

"I did a couple of the Out of the Darkness Walks," says Copeland, referring to the marches to raise awareness about depression (which he calls "the scarlet D, our last stigmatized disease"). "I was an honorary chair two years ago; there were people carrying pictures of their loved ones and I was amazed at how many pictures of 19-year-old boys there were. There's something about boys 18, 19, 20 years old—college age. And whenever I perform this show at colleges the organizers will tell me they had several students come up to them in tears afterwards," saying they suffered from depression.

What is it about comedians and depression, I ask him. "Most comedians are the most unhappy people you'll ever meet," he says. "With the exception of Jack Benny, one of my comedy idols and Jay Leno; they were the only two comics I ever heard of who had happy well-adjusted childhoods.… For most real comics the happiest time of their day is that 20 minutes that they're up on stage."

Copeland began performing when he was 18. He got the bug to make people laugh when he performed in plays in high school and soon was hitting San Francisco's comedy clubs, using his fake ID to see performers like Williams, Dana Carvey and Bob Goldthwait, all part of the vibrant scene there then. Like many comics his age, seeing the first Richard Pryor performance film was a revelation. "I'd never seen comedy that real," he recalls. "He talked about shooting the tires out of his car; it's considered the most brilliant 90 minutes of standup ever filmed. That made me think I want to try this."

A former high school coach, Tommy Thomas, had just opened his own comedy club, Tommy T's down the street. "I called and said, 'I wonder if you have an open mike night?' and he said, 'No, but I have a comic sick tonight. Can you do 15 minutes?' This if 5 o'clock, the show was at 9. But I'm 18 so I go, 'Sure!' I opened the paper and wrote 15 minutes of jokes; all I remember is that the Falkland War was going on and I wrote jokes about that. And there were 12 people in the audience but I went on and they laughed and I felt this rush."

As most addicts learn, those moments between the rushes can be quite painful. Copeland's education has included coming to terms with his need for attention but also the legacy of depression in his family. "I lost my mother when I was 14; she was 36—sarcoidosis, the same thing Bernie Mac died from. I realize now she was depressed… she would go in her room—it was my mother and my grandmother and me and my four little sisters—and she would go in her room on Friday and we wouldn't see her until Sunday. Grandma would give us plates to take up to her and knock on the door and give her a plate and then come back later and take the empty plate. … Then she would come out and everything would be fine."

At the end of each performance, Copeland exhorts his audience to talk about what they are feeling, or not feeling, and for parents, spouses and even children to be on the lookout for the warning signs of depression themselves. "If you know what the signs are—your brother loves going to the racetrack and he never goes anymore—you have to try and reach out." He has been gratified by the response, both from people who have come to him afterward and even an Iraq war vet who credited Copeland's show with waking him up to his PTSD.

"You should be no more ashamed of depression than you should if you had Lou Gehrig's disease or cancer," says Copeland. "As I say at the end, 'If I can stand up here for 70 minutes and spill my guts to strangers, you can tell somebody that you are having thoughts that are not in your best interest.'"