Dubious investment companies have swindled as much as Rs 60,000 crore from depositors in four states exploiting legal loopholes

Dubious investment companies have swindled as much as Rs 60,000 crore from depositors in four states exploiting legal loopholes.

Rapacity is a word Kulamani Naha is not familiar with. Greed, perhaps. But he sure knows what it must feel like. Naha, 62, retired as a deputy director from the Odisha government's textiles department in 2012 and was looking forward to spending a quiet, uneventful life with his family in Bhubaneswar. Instead, the last two years have been spent chasing lawyers and dealing with litigation. And asking friends and relatives to help him out whenever he needs money. His folly: falling for that promise of a little extra interest and investing all his savings and retirement benefits of Rs 30 lakh in the Artha Tatwa Group.

Artha Tatwa, registered in Bhubaneswar and operating in Odisha and West Bengal since 2010, claimed to be into housing and infrastructure projects, among others. It promised investors such as Naha that their investments would earn interest of 18 per cent per annum. But all that Naha got to see was small amounts that totalled Rs 2 lakh over two years. And then the company went bust. "I am virtually on the street," says Naha. "Now I have to depend on my relatives and friends for money."

For Subhash C. Ghosh, 46, who runs a coaching centre in Barasat in West Bengal's North 24 Parganas district, it was not just the lure of high interest but also the 20 per cent commission Sun Heaven Agro India Ltd promised for every new investment he brought. He invested Rs 1.75 lakh in the Barasat firm while Suranjan Mondol from neighbouring Ichapur district invested Rs 5 lakh and became an agent as well. Sun Heaven went belly up in 2013 and the two were among thousands of investors whose savings vanished.

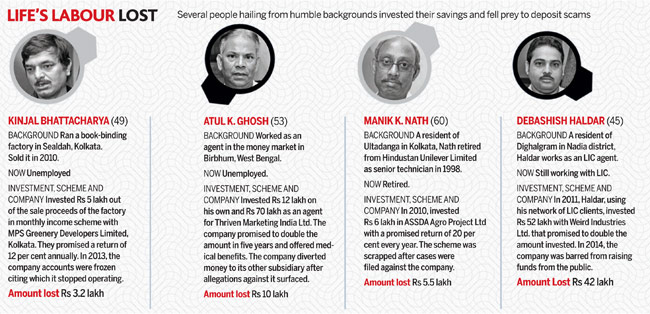

Then there are daily wagers such as Sanatan Behera from Khorda in Odisha who deposited Rs 15,000 in two years in a company called Systematic Fund Management Ltd for the 13.5 per cent annual interest it promised. Or Sealdah businessman Kinjal Bhattacharya, 49. Balasore widow Saraswati Dash, 45. Nadia district Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) agent Debashish Haldar, 45. Shaukat Ali, 71, a retired government employee from Dhubri district in Assam.

After a point, the names don't seem to matter. Neither do the firms in which they invested nor the amounts tagged against them. There is a familiar ring of financial scandal surrounding their tragic, largely middle-class stories across Odisha, West Bengal, Assam and Tri pura-an eastern cor-ridor where scamsters mushroomed in the dozens in the last decade and took the gullible and their investments on a big ride. That the region happens to be economically and financially poorly developed, with few clean options available for people to invest in, is not a coincidence. It was fertile ground for a dubious harvest.

While the headlines have largely focused on the Saradha chit fund scandal because of the alleged involvement of the high and mighty of West Bengal, CBI and Enforcement Directorate (ED) investigators claim that 194 dubious companies, including Saradha, collected and swindled as much as Rs 60,000 crore from 10 million depositors over an eight-year period until the bubble burst last year. To get a sense of the size of the alleged fraud, the Commonwealth Games scam of 2010, in comparison, was put at Rs 5,000-Rs 8,000 crore and the Satyam Computers scam of 2009, labelled India's largest corporate scam, was estimated at around Rs 24,000 crore. The Sahara group, whose chief Subrata Roy is in jail, too owes investors Rs 24,000 crore.

But the losses are not just finan-cial. According to the police, at least 106 people from these four states have killed themselves after realising they were duped. Investigators scour-ing through a mountain of evidence say that inside the complex maze are state government officials, MPs, MLAs and bank employees, among others. The CBI has registered 44 FIRs in Odisha and 13 in West Bengal while the ED is probing four cases under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA). While the CBI has arrested 46 people, the ED has five people in its custody and has attached property worth Rs 1,500 crore belonging to them. If this is not criminal avarice, nothing is.

That's not all. Although the ba sic instinct of all the suspect schemes that have come to the fore in the four states are the same as investment frauds in the past-induce and con greedy investors and flee with their money- some of their tentacles are thought to have extended to newer, more dangerous and sensational areas. CBI and ED sleuths are now investigating if Trinamool Congress (TMC) leader Madan Mitra, arrested in the Saradha case, had used a man named Rezaul Karim, an alleged member of the banned terror group Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), as a chit fund agent to bring in investors. Karim is alleged to be a bomb-maker and was arrested by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in connection with the bomb blast in West Bengal's Burdwan last year. Karim is also alleged to have met Gautam Kundur, a director in the Rose Valley Group of Odisha which is accused of swindling Rs 15,000 crore. Mitra however claims the Karim involved worked for him and is not the alleged JMB member. Kundur claims the Karim he met in 2011 was an inves-tor from Bangladesh.

The CBI and ED are also investigating if Vijay Mallya's East Bengal Football Club and United Mohun Bagan club received Rs 6 crore from Saradha group as sponsorship. This money, it is suspected, was trans-ferred to another account from where it was used to pay foreign players in the Indian Premier League (IPL). United Breweries spokesperson Sumanto Bhattacharya however said the company had "no knowledge" regarding the suspected sponsorship of Rs 6 crore. "Day-to-day management is in the hands of respective clubs. They should be asked," Bhattacharya said in an email to INDIA TODAY. He also denied allegations that money received by the two clubs was used to pay IPL players. "RCB (Royal Challengers Bangalore) has no connection whatsoever with United Mohun Bagan or United East Bengal. All player payments are monitored and audited by IPL to ensure compli-ance with the auction cap," he said.

THE CYCLE OF LIE

Investigators probing the cases in the four states say a majority of the 10 million investors who were duped were the poor or belonged to the lower middle class from villages and small towns. And many of them did not have access to formal banking channels. The new firms, on the other hand, offered returns worth anything from 12 to 40 per cent per annum and indulged in high-decibel advertising and endorsements. "Until a few months back, it was difficult for them to open bank accounts since know your customer (KYC) norms were so stringent. Many of them do not even have valid address or identity proofs," says Subir Dey, who is the convener of the Kolkata-based All-India Small Depositors and Field Workers Protection Committee.

Besides promising tantalising returns, the companies also worked through informal channels of agents. And even though most of them did not do any legitimate business they claimed in their advertisements, they managed to pay back some initial investors from funds collected from later investors or simply return the money collected originally, creating an environment of trust and getting investors hooked. "They asked me to become an agent for their company and promised a commission of 20 per cent," says Ghosh of Barasat. The company had 17 branches in remote parts of Assam, Odisha and Bihar. "They told us that they would pay a commission of 70 paisa for every Rs 100 of new investment," says Mondol from Ichapur.

There were also other newer and ingenious ways to lure investors. The Rose Valley Group, alleged to be behind the biggest fraud schemes, cast its net with the offer of owning land, apartments and travel besides eye-popping interest rates on depos-its. Prospective investors were told they could own land, an apartment or go on holidays by either making a one-time payment or in instalments. The investors could also get their original investment back along with inter-est at the end of a prescribed peri-od. Rose Valley apparently had land banks across West Bengal includ-ing in Rajarhat, Durgapur, Salboni, Jhargram, Bankura, Saltora, Bagnan, Malbazar, Siliguri, Birbhum, Malda, Ranaghat and also in Odisha, Tripura and Madhya Pradesh. Although some investors were allotted land, the allotments were found to be provisional. The company also tied up with hotels and travel firms to allow depositors to go on holidays.

A forensic audit report submitted in February 2014 by Hyderabad-headquartered chartered accountants, Sarath & Associates, to SEBI and quoted by the Supreme Court while ordering the CBI to probe the Saradha group, captured the modus operandi in shocking detail. Poor investors who invested as little as Rs 100 would receive maturity amounts after one month and truly believe the promised return has come to them, the report said. "What the investor does not realise is that Rs 100 was RETURN OF THE INVESTMENT AND NOT A RETURN ON THE INVESTMENT," the report said. With early investors receiving their promised returns, the "promo-tion of the investment comes across as genuine and instils an almost irre-sistible urge in friends and relatives to invest as well", it added.

But the vicious cycle does not last long. With hardly any legitimate business activity, the schemes con-tinue only for as long as new inves-tors ensure cash flow. As the number of old investors outnumber those being snared afresh and there is an imbalance in the cash flow, three outcomes are possible, Sarath & Associates said in the report: "One, the investment promoters disappear, taking the money with them. Two, the scheme collapses of its own weight and the promoters have a problem paying out the promised returns and as word spreads more people start asking for their money, creating a run on the bank situation. Third, the investment promoters turn themselves in and confess."

The one big difference in the unravelling scandal though is the alleged political links of the firms involved in raising deposits, a point investigators say is underlined by the probe into the Saradha scam. What however has remained out of the spotlight is the alleged diversion of funds to a wide range of sectors of the economy: construction and real estate, sports sponsorships, newspapers and television channels, contracts with film actors, painters and other celebrities, hotels and tourism, health services and microfinance, among others.

Financial experts say monitoring, auditing and regulating chit funds and deposit schemes is one area where state and central governments and independent authorities have consistently failed investors. Although some states have passed laws to restrict the collection of money from the public, the absence of a central law has meant suspect firms set up shop in states without such laws and expand their operations to states with regulations. Investigators say valuable time is lost when states try to work with each other to crack down on a fraudulent fund, allowing scamsters to siphon the money and flee.

In Odisha, companies are known to have exploited loopholes in the Orissa Self-Help Cooperative Act. The act, framed in 2001 by the Naveen Patnaik government, was meant to boost the cooperative movement in the state but it instead allowed the rise of scores of chit fund companies. Until March 31 last year, there were 979 credit and multipurpose self-help cooperative societies or chit funds registered under the Act before it was repealed.

Experts also feel that there is a need to appoint a central regulatory authority to resolve the woes of the hapless victims. "Because of a laxity in probes by RBI, SEBI, Serious Fraud Investigation Office (SFIO) and ED, there is need for a central regulatory committee. We have submitted in our petition that all these bodies should be under one umbrella. If required, a retired judge can be appointed as the commissioner. At least all those who lost their money can get it back," says senior advocate Subasish Chakravorty, counsel for the All India Small Depositors and Field Workers Protection Committee.

It is a demand that has been made more than once in the past, and one that has been buried under bruising turf wars that have marked the corridors of the country's financial authorities. However, with a govern-ment that seeks to burnish its commitment to financial inclusion and good governance in power at the Centre, the timing is apt to dust those files and push a national panel through. If not help the victims in eastern India get their investments back, the Narendra Modi government can at least prevent future frauds. Follow the writer on Twitter @rahultripathi

To read more, get your copy of India Today here.