- India

- International

Drought in Marathwada: Ground water levels dipping every year, focus shifts to conservation

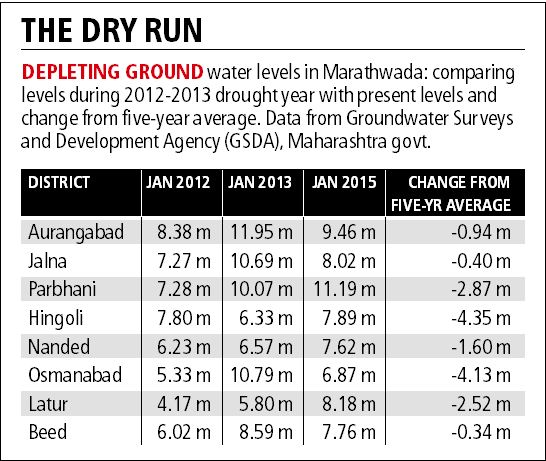

Aurangabad district has seen a fall in average depth of ground water level in the month of January, from the five-year average of 8.52 metres to 9.46 metres, a dip of 0.94 metres.

The more alarming news, say officials, is the continuing dip in water tables in the region over the last five years.

The more alarming news, say officials, is the continuing dip in water tables in the region over the last five years.Of the 76 talukas that comprise Marathwada, 61 show a drop in ground water levels compared to the previous year’s post-monsoon data. But with monsoon 2015 having provided just over 53 per cent of the already poor average rainfall of 779 mm in the region, the dip in ground water levels is hardly surprising.

ALSO READ: Only children, old and crippled left in parched villages

The more alarming news, say officials, is the continuing dip in water tables in the region over the last five years, alongside a huge spurt in digging of wells and borewells in urban and semi-urban areas as well as on farm land.

According to data from the state government’s Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency, which monitors over 860 observation wells in Marathwada’s eight districts, Aurangabad district has seen a fall in average depth of ground water level in the month of January, from the five-year average of 8.52 metres to 9.46 metres, a dip of 0.94 metres.

The region’s most critical dip in ground water levels this year appears to be in Hingoli district, where the average ground water level this January was 7.89 metres, a dip of 4.35 metres from the five-year average of 3.54 metres. Basmat taluka leads the fall at 7.10 metres less than the five-year average.

Other districts with a serious dip in water levels include Osmanabad district, where average water level this January was 6.87 metres, down from the five-year average of 2.74 metres. Six of Osmanabad’s eight districts have seen a dip of over 4 metres in comparison with the five-year average.

[related-post]

“In my 30-odd years as a farmer, I have never seen my farm well dry up completely. Not even in 2012,” says Pandit Nimaji Chavan, 60, whose two acres of cotton in Parbhani district have yielded absolutely no output this year. “They keep telling you there is no water shortage this year. I don’t know what that means,” he says. Parbhani’s January level has fallen from the five-year average of 8.33 metres to 11.19 metres, a dip of 2.87 metres.

Chavan is referring to the Maharashtra government’s opinion that despite a crippling agricultural drought in all of Marathwada’s 8,139 villages, drinking water is unlikely to be a serious crisis at least until May.

Compared to 1,730 tankers in February 2013, only 349 tankers were being despatched by the government to provide drinking water in the state’s worst-hit villages at the end of January this year, including 282 in Marathwada. Also, Jayakwadi dam, the region’s largest, has 26 per cent water storage as of February 2, almost twice the availability in February 2013.

But whether the government is able to provide tanker water to farmers is not the issue for the long term, says Dr Suresh Khanapurkar, retired government geologist and promoter of what is now called the “Shirpur pattern” checkdam to harvest and collect rainwater, a cost-effective solution that Khanapurkar impressed even former chief minister Prithviraj Chavan with.

“There is no real scarcity in Maharashtra, it’s all man-made,” Khanapurkar says. “We have replicated these checkdams in 55 villages in drought-prone areas with great success,” he says, adding that sustainable solutions to drought must naturally include serious water conservation programmes instead of a firefighting approach every drought year.

The Devendra Fadnavis government’s Jalyukt Shivaar Abhiyaan to drought-proof the state over the next five years has a stated commitment to better water management, conservation and ground-water recharging.

But alongside, questions on how to use the scarce water resources of the region remain. Parineeta Dandekar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) says, “Seventy factories in Marathwada continue to crush cane. Each needs lakhs of litres of water every day in the crushing season which coincides with the drought — between November and March.”

Apr 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05