Though matrimonial ads have changed substantially, the emphasis on looks, caste and income persist, mirroring the complexities and paradoxical nature of Indian society, says Roshni Nair as she tracks listings down the ages

The matrimonial ad is an expert shape shifter. More than 300 years after its birth in London's Athenian Mercury newspaper in 1692 — in an advice column, no less — it has morphed into everything from an Edwardian-era lonely hearts ad to a Craigslist personal. Laugh or fret at its often inane claims and demands all you will (and most of us have), but the humble matrimonial listing won't be leaving soon. Not least in India, where it encapsulates hope, tradition and prejudice in just a few centimetres of ad space.

It's hard to pinpoint when the great Indian matrimonial ad was born. Breathing two-century-old dust off Mumbai's oldest newspapers at the Maharashtra State Archives Department doesn't pay off. Classifieds were limited to Sherriff's sales, auctions and announcements of births, deaths and marriages. But University of Nottingham professor HG Cocks, author of Classified: The Secret History of the Personal Column, has a faint idea."Many English papers had some circulation in the British Empire and contained ads from parts of the empire. A lot of those were from servicemen. So you could say there was an imperial market in the late 19th century, which was the real golden age of the matrimonial advertisement in Britain," he says.

Cultural historian Rafique Baghdadi thinks Partition was a catalyst for India's matrimonial ad boom, especially in Delhi. "Some papers actually grew on such listings. Since there was considerable migrant influx after Partition and new crowds didn't have 'connections', matrimonials were a way to find suitable matches," he says. Mumbai too had its share of refugees — most notably the Sindhis. But they, along with the Gujaratis, Kolis, Catholics and Parsis mostly married within their communities, he adds.

This is still prevalent, the growing number of inter-community marriages notwithstanding.

Inside stories

Vasai-based Parsi matchmaker Katy Marfatia's skills have tied 25 proverbial knots in 12 years. Which isn't bad for her community, she laughs. Even then, changing preferences have her worried. "Girls today don't want to marry anyone with the surname Daruwala, Batliwala, Toddywala — basically anyone who's a 'Wala'. Then there are Parsis in Vasai, Thane and Dahanu whom people from South Bombay don't want to marry because they don't want to move north. I shifted from Dadar to Vasai 27 years ago, after marriage. That doesn't happen now. What to do, tell me?" she asks exasperatedly.

Departure from tradition is a concern for Mahim's Marazban Maney, who's set up 11 couples in 22 years. And unlike most matchmakers in the community, the 46-year-old relies heavily on numerology and horoscopes. "If you were Parsi, I'd have matched you with a suitable boy because of your date of birth. Your mangal is very strong, and you ask a thousand questions," he says.

One may not be Parsi, but it is nice knowing there's marital room for someone who questions everything.

Maney's 'old school' matchmaking gives insights about long-forgotten Parsi customs. Such as an ancient dowry system where husbands paid wives' families. "Back in Persia, the boy would pay 30 percent of his income every month to the girl's parents for life. The belief was that since you're taking something most valuable (a daughter) from them, you should pay them. Parsis in Iran still follow it, but we don't. Of the 11 couples I set up here, only two follow this system," he says.

Speaking of dowry, we don't see demands (publicly) in today's listings. But there was a time when claims of having substantial dowry to offer were common. Sample this from page two of the January 4, 1960 edition of a Chennai newspaper:

Wanted for a fair, good-looking girl, 28, Bharadwaja Gothram, Moolam star, a Madhwa Brahmin youth between 30 and 35 in government service. Decent dowry. Please reply with horoscope and other details.

Then came the Dowry Prohibition Act 1961 after which dowry claims and demands ceased to exist openly in ads. A look at January 1970 matrimonial listings in a Mumbai daily is testament to slowly-changing preferences, priorities and mindsets:

* Educated, smart, attractive Maharashtrian girl from respectable family seeks tall, handsome, rich * Maharashtrian. Divorcee without encumbrances, 35 yrs, income Rs5000 monthly…

* Gujarati Jain boy, 28 yrs, seeks beautiful, intelligent bride. Caste no bar...

* Doctor, 34, Moslem, seeking female doctor or nurse. Graduates only, 20-28 yrs. Nationality and religion no bar.

* 41 yr old Tamilian college teacher with government accommodation in Bombay seeking smart, beautiful wife. Language, widowhood, divorce no bar.

* Respectable Bania widower with good salary on the lookout for a kind mother to three attractive, convent-educated children.

Of course, it's unfair to use few listings as measures of what the collective mindset of the day was. But one would be hard-pressed even today to find orthodox Jains, for example, who'd marry outside the community. "Gujaratis and Marwaris generally don't mind marrying each other. But among Marwari sub-castes — Agarwals, Oswals and Maheshwaris — the Oswals, especially Oswal Jains, are picky. They refrain from marrying Gujarati Jains too," says Taruni Shroff, a Walkeshwar-based matchmaker for the communities. Shroff works 14-15 hours a day and has set up 5,000 couples in 30 years. Her database is meticulously sorted into folders on the basis of age, sex and sub-sect or caste. Applicants are required to fill up forms, provide pictures and write remarks after meeting prospects — who Shroff zeroes in after noting the requirements and meeting families.

It's the same drill with Ram Sadhe, whose Glory Matchmakers in Andheri caters to Roman Catholics. Folders are arranged by sub-sect (Goan, Mangalorean, Anglo Indian and East Indian), sex, and age-group. Sadhe even has a file with clippings of competitors' ads that appear in the Catholic newsweekly, The Examiner. "The majority want to marry in their own sub-sects, but they aren't rigid. It's mostly the Mangaloreans who have the highest expectations," he shares. Sadhe, full of anecdotes, narrates an incident where a man had flown down from Australia to find a bride here. "He walked in with a photo of a Pakistani actress and said, 'I want someone like her'. Now from where will I get someone like that, that too from one community only?" he guffaws.

Though emphases on looks, caste, horoscopes and income persist, what has changed substantially are listings by prospective brides or their families. No longer is it 'taboo' to marry 'late', be a divorcee or a single parent. This transformation, says Dr Anuradha Bakshi, head of the Human Development Department at Nirmala Niketan College of Home Science, is best reflected in Indian metros, particularly Mumbai.

Why Mumbai? It has the best public transport network in the country, she feels, and that's a game changer. More transport options meant that women could travel freely to universities and offices, in turn encouraging them to secure themselves socially and financially. So both education and transport infrastructure emancipated the Indian woman and made her more assertive. "See the places with poor or limited public transport. Women may be more reliant on private vehicles, which in turn creates a sense of dependency," she points out.

But truly radical changes are yet to be realised. For even if people are now open to marrying divorcees, for example, it's mostly on one condition: that one is 'issueless' (read: childless). It's tougher for single or divorced parents to find a match, and for divorced women to come across a 'good find' as compared to divorced men. "There are paradoxical demands from single girls too," says Bakshi. "People want working women, but they want them to be 'home-oriented', 'traditional' and manage the household too."

But as soul legend Sam Cooke said, a change is gonna come. Hopefully soon.

The trailblazers

Whether she's aware of it or not, ailing octogenarian Prabha Panse is a torchbearer for those on the fringes of matrimony — the differently-abled. As far back as the '80s, Panse established a marriage bureau for the physically-challenged. Her success in forging over 500 marital bonds drove 22-year-old Kalyani Khona to set up Wanted Umbrella, an agency pushing for the inclusion of the differently-abled in mainstream society. Their Matrimony Project is one endeavour in this direction. "The differently-abled are India's largest minority, yet only five percent get married. Theirs is rarely a choice. Regardless of their personalities and qualifications, they're made to believe they can't get married," says Khona.

In just two months of operations, Wanted Umbrella has received 550 registrations. The applicant pool is as varied as they come: apart from those with visual and hearing challenges, there are former sex workers, people with autism and Down's syndrome, obesity and even someone with a minor criminal record (now reformed). "I don't judge. Everyone deserves an opportunity. There's full disclosure between involved parties. I connect people only if they're open to such arrangements," she explains.

It can be harder to find matches for those with mental impairments, Khona adds, but nothing's out of bounds. She cites the story of an applicant — an engineer — currently building a customised wheelchair for the one he wants to marry: a woman with cerebral palsy.

Meanwhile in Pune, Pradeep Dixit has kick started marriageforadopted.com, a platform for another group relegated to the marriage sidelines: adopted adults. "The biggest stigma general society has about adopted children is that they're all illegitimate. So they feel marrying one is a paap," he says. Adding to the problem is the hallowed role of birth and family jatakas (horoscopes) in fixing matches. In the case of adopted individuals whose birth dates and lineages may not be known, such ties are a no-no for many.

These unwritten prejudices, Dixit feels, will become obscure if people foot their own marriage bills instead of expecting parents to do so. "It's an accepted norm that Indian parents should fund and manage their child's marriage. But the moment parents decide upon a spouse is when certain obstacles emerge. Younger generations aren't as obsessed with certain customs and traditions," he says. Dixit is planning to work with adoption agencies to extend his reach and help adopted adults find companionship.

One would think popular matrimonial sites have, to some degree, made things easier for anyone considered 'atypical', but no. When actress, writer and transgender activist Kalki Subramaniam signed up on such websites and openly stated that she's transsexual, her profiles were deleted. This discrimination spurred her to start thirunangai.net, the world's first matrimonial website for trans women. Thirunangai ('transsexual' in Tamil) isn't active now, but she's determined to relaunch it by organising a Swayamvara in Chennai. And when it does resurface, she says, the website will be open to not just transsexual women, but trans men too. "Everyone, absolutely everyone, deserves a platform to find someone they can spend their lives with," she underlines.

Indeed, the 'marriageable mainstream' has much to learn from the very people it overlooks. "The priorities (of the differently-abled and others) are a sea change. They're not looking for models. Caste, religion and salaries don't matter. These are self-assured people who're simply looking for someone who makes them happy and will become a companion for life," says Kalyani Khona.

Amen to that.

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

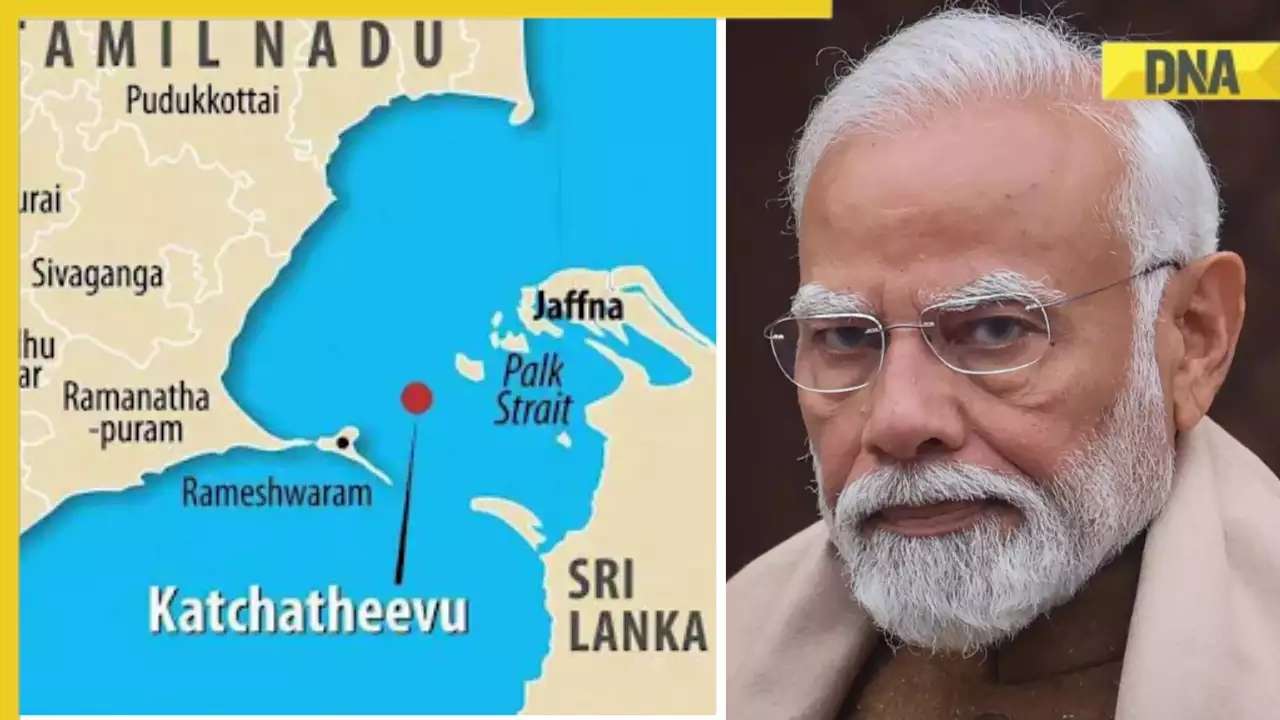

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)