- India

- International

Retracing Nathuram Godse’s Journey: In Gwalior house, son lives with a locked secret

His son, Upendra Parchure, is 82 years old now, and lives as a recluse. A lock nearly always hangs on the gate to the two-storied house.

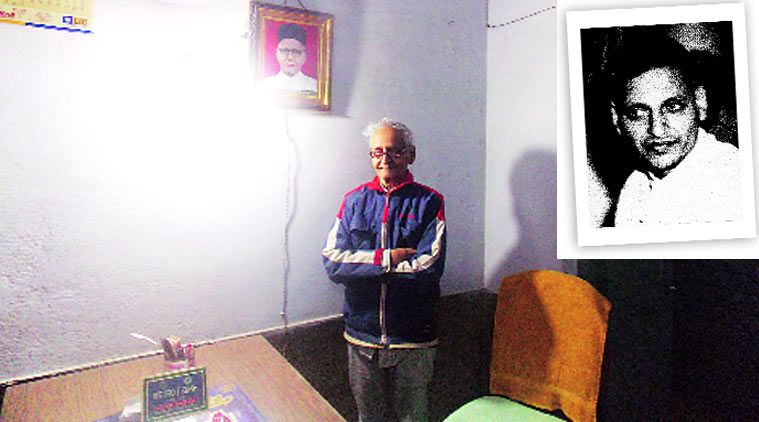

Parchure at his Gwalior home.

Parchure at his Gwalior home.

By the time Narayan Apte and Nathuram Godse returned to Delhi on January 27 for the second and final attempt on Mahatma Gandhi’s life, the equation between the two had changed. The man who had followed the lead of his more assertive partner had decided he would be the one to kill Gandhi.

They take a train from Old Delhi Railway Station to Gwalior. They are in search of a weapon.

The trail now leads to Vivekananda Colony, Phalka Bazaar, Gwalior. Here lives the son of the man who is believed to have arranged the 9 mm Beretta pistol, manufactured in Italy in 1934, with which Gandhi was shot dead. In 1935, Dattatreya Sadashiv Parchure started a branch of the Hindu Mahasabha in the princely state of Gwalior. He was also a leader of its militant offshoot, the Hindu Rashtra Dal, and, as a corollary, a fierce opponent of the Congress.

Part-1: Man who murdered Mahatma lives in an urn in Pune

According to his statement to the police after the assasination, Godse and Apte stayed at his house for a night. The next day, they bought the seven-chambered pistol from a dealer he knew. They paid Rs 300.

His son, Upendra Parchure, is 82 years old now, and lives as a recluse. A lock nearly always hangs on the gate to the two-storied house. Few neighbours know about the Parchures’ connection to the assassination. They are more intrigued by the great lengths the Parchures go to avoid people, and will tell you to persist despite the lock. Regular visitors to the house, like the maid, know the drill: once you call out to be let in, someone lowers a cloth bag tied to a string from the first-floor balcony. You take out a key from the bag, and lock the grill after you.

“I was only 18 then (when Parchure was arrested),” says Upendra, when he finally lets us in. “My father was very secretive. He wouldn’t talk about the past and wanted us to keep away from politics of all kinds. He was a revolutionary and remained so till the end,’’ he says. He is not forthcoming about his father’s role in the assassination, the politics he pursued or the repurcussions for the family.

Parchure practised Ayurvedic medicine at the family’s old house near Nadi Gate Bridge in Shinde Ki Chhavni. The family home has now been pulled down. He was detained on February 3, 1948, and reportedly confessed to his role in the conspiracy on February 18.

Part-2: A hotel in CP, and a failed bid to kill the Mahatma

He later retracted the confession, saying it was recorded by force, and was acquitted by the Punjab High Court in 1949. But the taint of the murder persisted. He was banned from Gwalior for two years and returned in 1952. He died in 1985 in this house in Vivekananda Colony. “He was a disciplinarian. He taught me medicine for nearly a decade in this very room,’’ says Upendra, who attends to patients for a few hours in the evening, the only time the gate is not locked.

The Hindu Mahasabha office in Daulatganj is a shadow of the once-powerful organization in the state. “But in 1948, the Hindu extremist movement drew a lot of support from the princely states like Gwalior and Alwar,” says Sucheta Mahajan, professor of history at JNU.

Nine days had passed since Madanlal Pahwa had been arrested for the explosion at Birla House, but neither the Delhi nor the Bombay Police had got wind of Godse and Apte’s frantic journeys. On January 29, they took a train to Delhi.

This time, they did not venture near the heart of the city, but booked a first class retiring room (Room No. 6) at the station in the name of N Vinayak Rau. Vishnu Karkare was the only member of the gang of seven who joined them. Stepping out of his room, as he set out on his task of “avenging” the Hindu cause, Godse would have surveyed a near-empty road leading to the bustle of Chandni Chowk.

Today, the room near the clock tower overlooks a sea of green-and-yellow autorickshaws, and a road choked with noisy traffic. “Before he set off to kill Bapu, Godse considered many disguises, even buying a burqa from Chandni Chowk and trying it on. But he nearly tripped while walking and gave it up,” says Tushar Gandhi, the Mahatma’s great-grandson and the author of Let’s Kill Gandhi.

At Birla House, Mahatma Gandhi had staunchly opposed the proposal to frisk visitors to his prayer meetings, even if he agreed to the police vigil being increased. “My faith does not allow me to put myself under any human protection at prayer time, when I have put myself under the sole protection of God,” he said.

In the last days of his life, Gandhi remained an unhappy man, talking frequently of death, his own,. “After the death of Ba (Kasturba Gandhi), especially, he seemed to be someone adrift, and that trauma, along with the fact of Partition, and his growing distance from Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel, were showing,” says Tushar. Two days before his death, he had told his grandniece Manubehn, “If I were to die of illness, you should declare me a false or hypocritical Mahatma… (If) someone shot at me, and I received his bullet…without a sigh and with Rama’s name on my lips, only then you should say that I was a true Mahatma.”

On the evening of January 30, the crowd at the Birla House grounds was growing restless. The Mahatma was late. Nathuram Godse, his weapon hidden in his clothes, had walked in — no police officer had stopped him on the way —and was waiting on the lawns. Karkare and Apte were behind him. Fifteen minutes past 5 pm, Gandhi rushed out of his room, flanked by Manu and Abha. As he climbed the steps leading to the grounds, Godse blocked his path, greeted him with folded hands, and pushed Manu to the ground. Three shots rang out. It was 5.17 pm.

American author Vincent Shean, who was present, later wrote: “I felt the consciousness of the Mahatma leave me then — I know of no other way of expressing this: he left me.”

So what did Godse achieve by killing Gandhi? In her home in Pune, Himani Savarkar looks into the distance and answers: “Even Bhishma had to suffer because he betrayed his desh. So did Gandhi.”

Sympathisers of the “Hindu” cause remain ambivalent. “I would say what Godse did hurt the Hindu cause more than anything. For 50 years, you could not speak up for Hindus for fear of being branded a traitor. It is only now that things are changing,” says Pune historian Pandurang Balkawade.

The urn in which Godse lives is brought out every year on November 15 for a ceremony organised by the Godses. Of the many people recently honoured at this “Balidan Diwas” was Pramod Muthalik of the Ram Sene. “My grandchildren read out parts of his speech at the trial. Three generations unite in keeping his memory alive. And we will continue to do so till India recognises what a great patriot he was,” says Nana Godse, Gopal Godse’s son.

In the Hindu Mahasabha office in Delhi, president Chander Prasad Kaushik, a saffron shawl draped over a saffron pullover, assures us that once the Delhi elections are over, “we will build many temples to Godse across the country.” In a corner of his room is a bust of a portly man, with chubby cheeks and a benign expression. It is who the Hindu Mahasabha have reimagined as Nathuram Godse, the lean, austere Chitpavan Brahman from Maharashtra. “Yes, it looks different from what Godse did. Par hum unko duble thodei hi dikhayenge? (How can we show him as a thin man?)”

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05