Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

Gino Bartali helped save over 800 Jews during the Holocaust

Bartali was one of the most revered cyclists in the world

Italian won two Tour de France titles during illustrious career

New film documents Bartali's role during World War Two

“He never asked nor accepted any reward, because he was good and simple and did not think that one did good for a reward.” (Primo Levi, If This Is A Man)

Gino Bartali wanted to keep it to himself.

How could a man, so famous and so revered, keep it a secret for so long?

“Good is something you do, not something you talk about,” Bartali once explained. “Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket.”

He was Italy’s very own version of Babe Ruth – a man whose personality, character and success transcended sport.

In the 1930s, Bartali, a son of Tuscany, was one of the leading cyclists in the world, a man admired by all.

He had won three Giro d’Italia titles – one of the three major European cycling events – in addition to his triumph at the 1938 Tour de France and was very much the country’s poster boy.

And yet for a man who lived in his life in the full glare of the public, a new film, My Italian Secret reveals a very different side to Bartali’s remarkable life.

Directed by Oren Jacoby, the film shows how Bartali was part of a secret Italian resistance movement which helped hide the country’s Jews during the Nazi invasion of 1943.

Using the handlebars on his bike to hide counterfeit identity papers, Bartali would ride to Jews in hiding and deliver their exit visas which allowed them to escape transportation to the death camps – he is credited with saving the lives of 800 people.

“He never talked about what he did during World War II,” said Jacoby. People loved him, they adored him. Italy was so proud of him.

“He risked his life to save others and it’s a story which Italy is now embracing.”

Wheels of fortune

Born in Florence in 1914, Bartali was a devout Catholic whose parents were married by the local Cardinal, Elia Angelo Dalla Costa.

It was Dalla Costa who recruited Bartali into his secret network at a time where much of Italy had been ceded to the Nazis.

In 1938, Italy’s Fascist regime, led by Benito Mussolini, enacted a series of anti-Semtiic laws which prevented Jews from working within government or education, banned intermarriage and removed them from positions in the media.

While some of the country’s Jews fled the country before the outbreak of World War II, those who stayed behind remained largely unscathed until the Germans began deportations in 1943.

It was at this time that Dalla Costa, working with Rabbi Nathan Cassuto, created a system which involved convents, monasteries and members of the general public hiding Jews in all kinds of ingenious ways.

Even after Cassuto was arrested by the Germans, deported and sent to his death, the secret network continued to operate.

Using the guise of long-distance training, Bartali would ride for hundreds of miles delivering documents while the Fascist secret police simply let him pass given their admiration for the cyclist.

Whenever he was stopped, he would simply ask that his bike not be touched since the technical set up was arranged to achieve maximum speed.

Eventually, Bartali was forced to go into hiding in the town of Citta Di Castello in Umbria, where he hid the Goldenberg family.

In the book, Road to Valour written by siblings Aili and Andres McConnon, Giorgio Goldenberg recalls how Bartali’s actions helped save his life and the lives of his family.

“There is no doubt whatsoever for me that he saved our lives,” said Goldenberg, who hid in Bartali’s cellar until the liberation of Florence in 1944.

“He not only saved our lives but he helped save the lives of hundreds of people. He put his own life and his family’s in danger in order to do so.

“In my opinion, he was a hero and he is entitled to be called a hero of the Italian people during World War II.”

It was not just the rescued who were grateful to Bartali, those who were involved in creating the counterfeit papers in Assisi also took courage from the cyclist’s fearlessness.

Worked in the counterfeiting business, Trento Brizi explained how Bartali’s influence gave him courage at a time where the Nazis began to get suspicious.

In the book, Road to Valor, Brizi said: “The idea of taking part in an organization that could boast of a champion like Gino Bartali among its ranks, filled me with such pride that my fear took a back seat.”

According to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, 7,680 out of 44,500 Italian Jews were killed by the Nazis.

While many Italians helped defy Adolf Hitler’s attempts to cleanse Europe of Jews, Bartali’s high-profile meant he risked playing a dangerous game.

And yet, according to Aili McConnon, he refused to take any credit for his role in saving Jewish lives.

“He was very modest about it,” she told CNN. “He held a profound sense that so many had suffered in a much greater capacity than he had. He didn’t want to be in the spotlight or diminish the contributions of others.

“As a cyclist and competitor, he could be a real loudmouth. He was very proud and very competitive.

“But what made him so fascinating, was his other side – the modesty which he possessed.”

“Real Heroes”

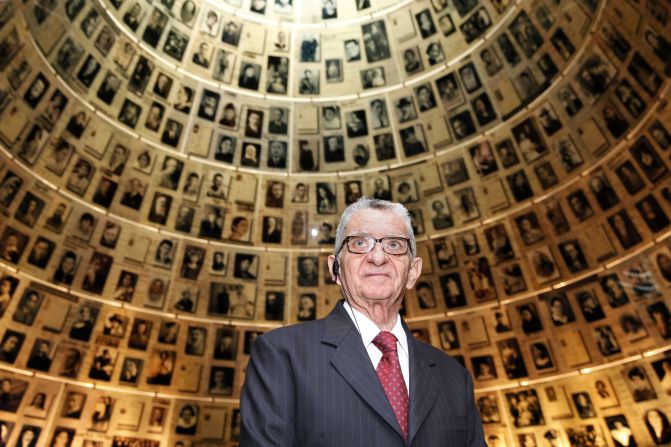

In September 2013, Bartali’s wartime heroism was honored in Israel when he was named as a “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem – Israel’s official memorial to Holocaust victims.

While Bartali rarely spoke of his actions before he passed away in 2000, his son, Andrea, attended the ceremony and met survivors, including Goldenberg, who had been helped by his father’s actions.

It was Andrea who helped push his father’s war time contribution into the public consciousness following years in secrecy.

“When people were telling him ‘Gino, you’re a hero,’ “He would reply, ‘No, no. I want to be remembered for my sporting achievements,’” Andrea Bartali told reporters upon his visit to Israel in 2013.

“Real heroes are others, those who have suffered in their soul, in their heart, in their spirit, in their mind, for their loved ones. Those are the real heroes. I’m just a cyclist.”

My Italian Secret has already had a profound affect on Italian society.

Its showing at the Rome Film Festival was widely lauded by critics and has helped Italy begin to acknowledge its past, according to Jacoby.

“We were overwhelmed by the response the film got in Italy,” added the film’s director, whose Jewish heritage comes through his father’s side.

“I think this topic had not been touched on or thought about since the war. It was a chance for Italy to come to terms to get to grips with chapter of history it hadn’t addressed.”

Having spent a summer in Rome as a 19-year-old, the story of Italy’s Jews and how ordinary Italians managed to defy the Nazis had always been at the back of Jacoby’s mind.

While he spent time learning from some of the great Italian directors such as Federico Fellini (Casanova), Ina Wertmuller (Seven Beauties), and Pier Paolo Pasolini (Salo), it was a meeting with a Polish filmmaker which left a lasting impression.

“One day, the professor who ran the course, a Polish filmmaker named Marian Marzynski, took me to lunch in a café in the Rome ghetto, meters away from a plaque memorializing the roundup of Rome’s Jews in 1943,” recalled Jacoby.

“He told me how he had survived the Warsaw Ghetto as a hidden child, protected first by ordinary people and later, by priests in a monastery, who all risked their lives to help him escape.

“I never thought, back in 1975, that almost 40 years later I would be given the opportunity to tell the story of Italian children who were hidden and saved, along with the story of Gino Bartali and some of the other heroes who risked their lives to do it.”

‘Il Morbo di K’

While Bartali’s heroics have caught much of the attention, the story of physician Giovanni Borromeo is equally remarkable.

It was by chance that Jacoby, filming in Rome during an early shoot, came into contact with Borromeo’s son, Pietro.

“We heard that a guy wanted to get in touch with us about the film,” recalled Jacoby.

“So he came and met us for lunch and what he told us was incredible – absolutely incredible.”

Dr Borromeo was a Roman surgeon who worked in the Catholic Fatebenefratelli Hospital on Tiberina Island in Rome.

There he hid hundreds of Jews after concocting a tale of a “deadly” disease which had engulfed the hospital.

“Dr Borromeo invented a fake disease to scare the Nazis off and prevent them from searching the hospital,” said Jacoby.

“He called it ‘Il Morbo di K’ and used it to protect the Jewish people who he was hiding.

“He would say to the Nazis, ‘hey, you guys can come in but you’ll get this disease and it could kill you’.

“He saved many people – but it didn’t really hit home until some of those he saved turned up at our screening. That was incredible.”

Bartali remained intent on being remembered for his cycling success – his second Tour de France in 1948 was remarkable given it came a decade after his first victory.

It was only later on in life after meeting Cassuto’s daughter that he agreed to speak about his experiences, though he insisted that he would not be recorded.

While Bartali’s cycling achievements are remembered each year in an event dedicated to him and fierce rival, Fausto Coppi – the annual Settimana Coppi e Bartali race – his legacy in the wider world lives on.

“He hid us in spite of knowing that the Germans were killing everybody who was hiding Jews,” Goldenberg’s son, Giorgio, says in Jacoby’s film.

“He was risking not only his life but also his family. Gino Bartali saved my life and the life of my family. That’s clear because if he hadn’t hidden us, we had nowhere to go.”