The New York Public Library recently started an Instagram series featuring questions that people posed to librarians in the days before Google. Apparently, librarians stored the more interesting queries for decades. So far, the series has featured etiquette questions ("When one has guests, who kisses whom first?" someone asked in 1946) and a health and science inquiry from 1962 ("What is the gestation period of human beings in days?"). As antiquated as this analog method seems, millions of people in jails and prisons with no Internet access still rely on librarians for answers that could be found in seconds online.

In an office building near the NYPL's central library, with big windows looking out on the famous marble lions, a team of four people answers questions from inmates through the library's Correctional Services Program. The program started decades ago and now runs lending libraries in prisons and publishes a guidebook to help people upon release. Responding to as many as 60 weekly letters isn't an official service, but it seems to be growing in popularity. "By word of mouth we get more and more every year," says librarian Sarah Ball, who supervises the program.

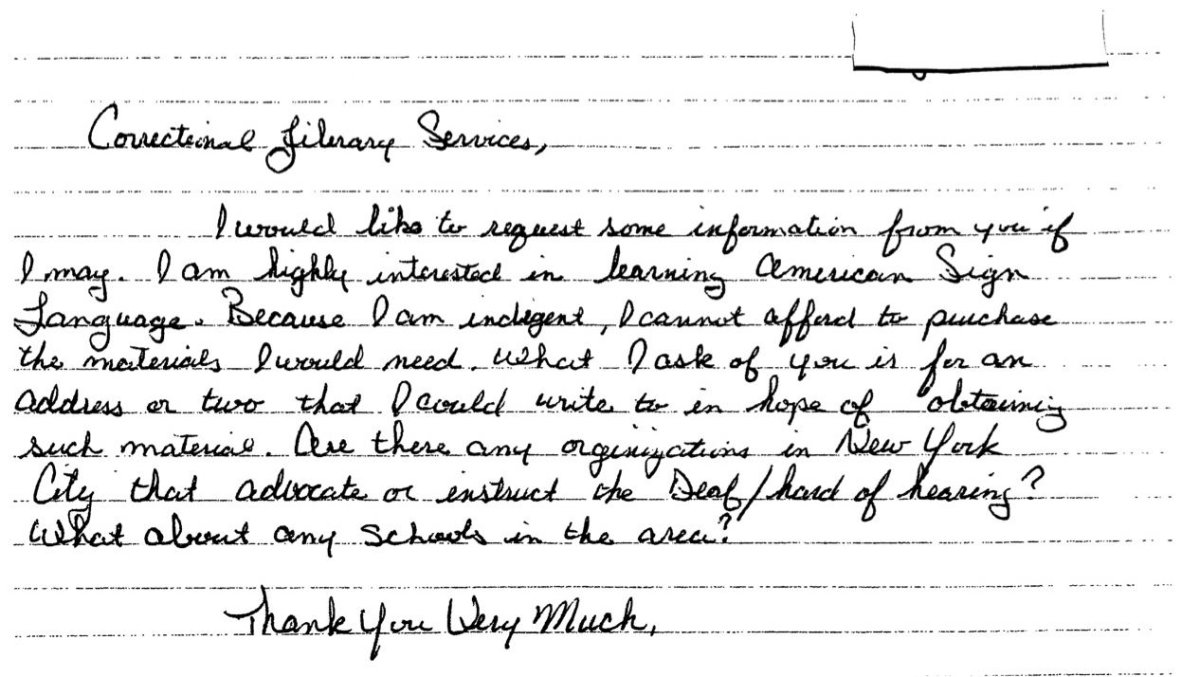

Most questions — 84 percent, responders say — come from facilities in New York state; the rest arrive from all over the country. Many have to do with life after incarceration, but others speak to the interests and curiosities of the more than 2.2 million people behind bars in the U.S. One, for example, wanted to know how to grow potatoes and start a farm. Another wanted to eventually start a diaper business and sought consumer data. There have been questions about the power of healing crystals, trumpet playing and Wiccan priesthood certification. There have also been many, many requests for baseball statistics, and one frequent writer always asks for rap song lyrics.

Some letters have included personal stories and illustrations; some were written in pencil on toilet paper.

"It's long overdue that we haven't found some kind of system where people can have access to the Internet [in prison]," Ball says.

A 2009 survey found that correctional facilities in only four states — Connecticut, Hawaii, Kansas and Louisiana — permitted some Internet access to inmates, though in all cases it was limited. In Kansas, only minimum-security inmates had access. In Louisiana, the Internet was only available to inmates within 45 days of release and for the purpose of job searches.

Federal prisons have increased access in recent years. Since 2009, those facilities have allowed inmates to send and receive emails through a system called TRULINCS. They can only correspond with approved individuals, and messages are subject to monitoring.

As the pile of letters at the NYPL grows — responding can take a month or two — Ball's team has enlisted the help of students at the Pratt Institute School of Information and Library Science. Two professors there just began their fourth semester of having students respond to the inmate questions. The process of answering usually starts with Google, associate professor Deborah Rabina says, and then students move on to resources such as newspaper archives and public records.

Rabina and Emily Drabinski, a visiting assistant professor, have written an article about their experience answering the letters that will appear later this year in the online journal Reference and User Services Quarterly.

The professors found that almost half of the requests (44 percent) were general reference questions, 35 percent had to do with reintegrating back into society (such as the location of halfway houses) and 21 percent were "self-help" questions (information that would improve people's time behind bars, such as regarding inmates' rights).

The only questions the folks at NYPL and Pratt won't answer, they say, are requests for personal contact information or legal advice. Ball says their page limit for responses is 10, but they use the fronts and backs and try to fit in as many words as possible.

While many of the questions have to do with hobbies and preoccupations, the lack of Internet access has more significant implications. For one, people trying to get degrees while behind bars are at a disadvantage when it comes to research materials. Also, missing out on technological advances while in prison makes reintegrating into the real world more challenging.

"People need to have practice using the Internet, just to get back into the swing of things when they're released," Ball says.

Rabina agrees: "If you want people to successfully reintegrate into society upon their release, being able to have access to this service is essential."

Students behind bars have an especially hard time. In order to obtain a Bard College degree, the incarcerated people participating in the Bard Prison Initiative must complete research papers that can run more than 100 pages. With no Internet access, those students rely on "research assistants" who must bring to the prisons paper materials that are subject to search.

The reference question letters seem to be unique to New York. In other states, where prison populations are greater, librarians say they have received such questions from inmates, but the requests are less common and they have no team devoted to responding. The director of branch library services at the Los Angeles Public Library says its reference staff receives only 20 or 30 reference question letters from inmates per year. A spokeswoman for the Phoenix Public Library says it receives around one a month, and its policy is not to answer any mailed reference questions, regardless of the origin.

Nicholas Higgins, Ball's predecessor at the NYPL and now director of outreach services at Brooklyn Public Library, which also receives letters from inmates, says he believes incarcerated people write them not only for reference answers but also "as a human connection, some sort of outlet to have that conversation with people who are willing to listen and respond."

A library is meant to "allow access to information to everybody in your community," Higgins says, adding that correctional facilities too often are "a system that resists that sort of access to information."

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that more than 6.8 million people are behind bars in the U.S. While that number makes up the country's overall correctional population, only an estimated 2.2 million are behind bars, while the rest are under correctional supervision, which includes conditions such as parole and probation.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Max Kutner is a senior writer at Newsweek, where he covers politics and general interest news. He specializes in stories ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.