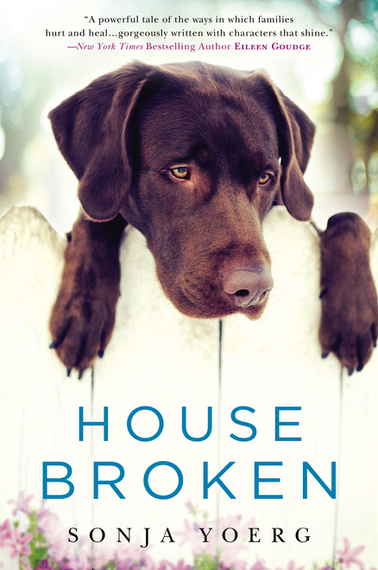

While Sonja Yoerg, author of the novel House Broken (Penguin/NAL, 2015) and the non-fiction, Clever as a Fox (Bloomsbury USA, 2001) calls herself "the queen of harebrained schemes," Library Journal, puts Yoerg "on par with established women's fiction authors such as Jennifer Weiner and Sarah Pekkanen." House Broken tells the story of Geneva, a veterinarian, who reluctantly allows her alcoholic mother to recuperate in her home and uses the opportunity to delve into family secrets. It's told from three points-of-view: Geneva's, her mother's and Geneva's 16-year-old daughter.

As an author of both non-fiction and fiction, how is your writing process differ with fiction versus non-fiction?

My non-fiction book started with a detailed proposal, so the skeleton of the entire work was there. Plus, I had written it in my head over the previous couple of years, so I knew just what I wanted to say. There were a few surprises, but not many.

Writing House Broken tells the story of Geneva, a veterinarian, who reluctantly allows her alcoholic mother to recuperate in her home and uses the opportunity to delve into family secrets. It's told from three points-of-view: Geneva's, her mother's and Geneva's 16-year-old daughter. could not have been more different. I had no idea where the story was going. I started with Geneva, a veterinarian who likes her ducks lined up and swimming in formation, and set about making trouble for her. I'm a bit of a control freak myself, so it was unnerving to be writing in the dark.

I loved the book group questions at the end of House Broken. What do you think makes for a great book discussion? What questions would you most like to talk about at a book group for House Broken?

Coming up with book group questions felt a lot like designing exam questions for my college students. The best questions are those that go beyond the material, in this case, the actual story, and ask "What if?" What if it were set elsewhere? What if the character chose Door Number Two instead of Door Number One?

I can't wait to talk to book groups! I want to hear what they thought, how their life experiences and reading histories pulled different aspects of the story into relief. Language is not solid. It bends and twists and molds itself to the reader. I want to hear about that.

I recently attended an event by Elizabeth Gilbert; she talked about how personal her recent book, Signature of All Things was, noting that in some ways it reveals more of her own life that her memoir, Eat Pray Love. As you look back on House Broken, where do you see yourself?

When I wrote House Broken, my daughters were poised to leap from the nest, so perhaps it was inevitable I would write about a family with two high-schoolers. At that age, kids are so close to being independent, and yet are uniquely positioned to completely mess up their lives. I know many parents feel, as the main character, Geneva, does, that they are one unlucky break away from complete disaster.

You make great use of multiple points of view. What process did you use to write from those different generations? How did you weave the stories together or did you write then in an alternating fashion? What are your takeaways from this process? What did you learn about voice in fiction?

The first few chapters I wrote from the point of view of Ella (Geneva's daughter) and Helen (Geneva's mother), I used first person to establish the voice in my head. When I felt I had rhythm and intonation, I rewrote those chapters in third person. I wrote the chapters in order, shifting between the different perspectives, but I sometimes read through all the Ella chapters, for example, to check for continuity. My secret weapons for Ella's voice were my teenage daughters, who acted as beta readers, and kept Ella's voice true. As for Helen, the 65-year-old Southern drunk, well, I must've been her, or her best friend, in a previous life.

Geneva's character was the most complex because she was juggling everything: her kids, her mother, her job, her husband, and her past. Her daughter and mother are both more selfish, and therefore more straightforward to write, and provided relief for me from Geneva's emotional intricacies. I suspect readers will feel the same.

Voice comes from the heart. It took me a while to find Geneva's voice because she is very logical and reserved. The events of the story drew her out into the open, where I could see all of her, and understand her. Voice, I discovered, isn't something a writer bestows upon a character. It's a gift from the character to the writer who listens.

You started writing later in life. What changed for you after 40?

I don't think about my age. I think about what I want to do and I figure out how to do it. It never occurred to me that I might be a little long in the tooth for writing my first book or novel. It is, after all, a book, not the swimsuit edition of Sports Illustrated.

I did, however, consider that my daughters were about to leave home for college. They are a year apart so there would be no easing into empty-nesthood. It seemed a perfect time to begin afresh, and I was lucky to have to ability to do so.