- India

- International

Sons of toil: Heart wrenching tale of migrants labourers in govt projects

They're building some of the grandest projects from the biggest crude oil refinery to the tallest commercial building.

Sanand became a prominent industrial hub after the opening of the Tata Nano plant there in 2008

Sanand became a prominent industrial hub after the opening of the Tata Nano plant there in 2008

‘Every day, the second I get out from tunnel, I call my family’

By Samudra Gupta Kashyap

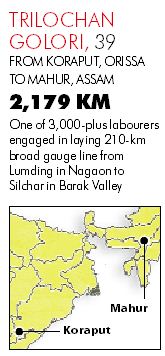

Trilochan Golori, 39, watches as a group of workers prepare concrete and plaster it over a rock through which a railway tunnel will pass. Water seeps through and floods the tunnel, slowing down the work. “Jaldi kar (hurry up),” Golori instructs impatiently.

Golori is from Adiguda village in Koraput district, Orissa, and speaks only broken Hindi, but it is the only way he can communicate with the workers with him — from states across India such as Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Over 3,000 labourers, 80 per cent of them migrants, are at work on a 210-km broad gauge line from Lumding in Nagaon district to Silchar in Barak Valley in Assam, through the Barail mountains, over 500 metres above sea level.

Scheduled to be operational by March 31, 2015, the line will improve connectivity of Assam to Manipur, Mizoram and Tripura, and will pass through 17 tunnels and over 79 major bridges and 340 minor bridges. Golori is employed with Hyderabad-based SSNR Projects Pvt Ltd. Since 2012, he has been supervising the drilling of the rocks.

Golori works inside the 1,687-metre-long Tunnel No. 7 for 12 hours a day. As mobile phones can’t be switched on inside, the first thing he does at the end of the day is call his family to tell them he is safe. For, apart from being one of the more inhospitable territories of the country, Barail mountains is one of the most dangerous places to work in. Besides wild animals and mosquitoes, Golori has to contend with militants.

Between 2006 and 2009, the Dima Halam Daogo (DHD) and its factions killed at least 70 people and abducted dozens of labourers working on the project, causing the Railways to miss several deadlines. The DHD is now dissolved, but other groups remain. Just two weeks ago, militants killed two locals.

“My family was very worried about me shifting to Assam. I call them every day,” says Golori, who has three sons, aged 16, 12 and 6 years. The family has a small plot of land on which they grow rice and vegetables.

Golori could not study beyond Class IX because of poverty and has ensured all his three sons attend school. “I wanted to become an Army jawan. But poverty and fate made me a miner,” he says.

It is his 23rd year of working that has taken him across the country — to a limestone mine in Maharashtra, a hydroelectric power project site in Uttarakhand, and to a tunnel site on the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. “Assam is my riskiest assignment till date,” he says. In the category of “skilled workman” now, he earns Rs 650 a day for an eight-hour shift, and Rs 600 more for putting in extra four hours.

Because of the risk, Golori’s company doesn’t allow workers to leave the camp they live in after duty hours. “There is nothing here for entertainment, except watching TV,” he says.

Golori lives with 42 other workmen in the makeshift barrack made of tin sheets and timber planks just outside the tunnel’s northern entrance. The company provides free food and accommodation.

The Territorial Army provides security to the men. “We go out shopping in a group with security personnel accompanying us,” Golori says.

Golori last visited his family in June, and will not get any more leave now. The first train is scheduled to run on the track by April 2015.

“I will then ask for a month’s leave to spend with the family,” he says. “There are a lot of things pending, including repair of the house.”

‘If only there was work back at home’

By Esha Roy

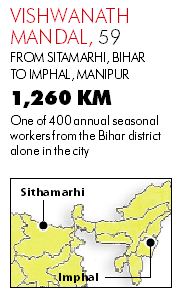

Fifty-nine-year-old Vishwanath Mandal was just 16 when he first came to Manipur. He had never heard of the place. With his family battling poverty, Mandal was persuaded by his brother-in-law to travel from the northernmost part of Bihar to the easternmost part of India to find work. It was an August morning that Mandal left the small village of Parginiya in Bihar’s Sitamarhi district for Imphal.

Over the years, his brother-in-law passed away, Mandal got married and had four sons and a daughter. But, every year, come August, he makes the trip to Imphal. “Saawan ke baad aata hun aur baisakh ke pehle chala jaata hun (I come after monsoon and leave in April),” he says.

Mandal is one of the approximately 400 seasonal workers from Sitamarhi alone on Imphal’s streets at any given time. He ferries goods across the city’s sole market area — a garbage-strewn Bazaar, a hub of business and trade — occupied by the state’s four lakh Mayanag or non-Manipuri population.

“On an average I make around Rs 200-300 a day,” says Mandal. That’s not much, forcing his eldest son too to pitch in with a job stitching jeans at a factory “somewhere in Delhi”. But it’s more than what Mandal would make in his village. The work there, mostly on other people’s land, is seasonal.

He has four other children, between the ages of 9 and 15, the youngest a daughter. Like Mandal, none of his children has ever gone to school. Come harvest season, all work as hired help in fields. That’s the time Mandal too is back home.

Mandal’s memory of his growing-up years involves this shuttling — between two states, and between poverty at home and, increasingly, insecurity in the other place he calls his own. “Things were never this bad earlier. Locals were actually quite friendly. Now we feel scared to live even in the Bazaar area,” says Mandal.

On December 21, a blast near Khoyathong, a transportation hub next to the Bazaar, left two migrant workers dead and four injured. Goods from across the country arrive at Khoyathong, to be transported across the city and to other parts of the state. It is migrant labourers such as Mandal who carry the foodgrains, utensils and other goods to godowns, shops or other trucks. A week ago, another IED explosion, in the heart of the Bazaar, had killed two and injured three.

Looking around at the stepped-up security, Mandal smiles nervously. His boss Mohan Shah, a strapping six-footer, also from Sitamarhi, gathers his team around. “It’s been difficult to get work today,” he says. “Police grounded our thelas. If things continue like this, we will have to leave early.”

It isn’t just the blasts, Mandal says. “When we are just walking, someone hits us, the police even. We earn so little, but they come and take our earnings, sometimes at gunpoint, and tell us to leave… We would actually never come here if there was work in our own district.”

As Shah decides they will give work a try the next day, the group gets up and walks to the other side of the Bazaar, to Roopmandir. It is hidden away in a small square, walled-in by tall buildings. Mandal and the others walk past a tailor shop, a cheap mobile store and a barber playing Bollywood music. A smelly, tunnel-like stairwell leads to clusters of dark rooms on various floors. The workers use the light from their mobile phones to climb.

The room that Mandal shares with six others is small, with a broken window at one end. The walls are black, caked with years of dirt. The blackness also covers the two clotheslines, the several stools and the sole bed. Clothes, jackets and grimy towels are everywhere.

The room rent is Rs 1,500 a month, after a Rs 10,000 deposit. The rent is divided equally among the six. They leave every morning in search of work and come back at 6 every evening. They never stray from this routine, and stepping outside the area is out of the question. “We heard that three workers from Guwahati left the Bazaar area a couple of months ago and were later found dead,” whispers Mandal.

With no television, no radio, their only source of news are other Bengali migrants. Shah’s son, 23-year-old Santosh, enters just then carrying a large fish. “They told me it’s Christmas tomorrow so take it, we’ll give you a deal,” he grins, getting down on his haunches to scale the fish as a new Bollywood number plays on his cellphone.

‘Nobody has time to fight here’

By Parimal Dabhi

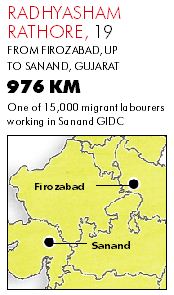

Radhyasham Rathore’s gaze and hands are glued to his cellphone, as he plays the latest version of Angry Birds. Occasionally, he takes a break to push back gelled flicks of his hair, bringing into sharper focus his biceps with a tattooed bull and a heart.

The 19-year-old seems unfazed by his dingy surroundings. Just out of sight behind him is a 10×15-ft room, cramped with eight mattresses lined in a row, each with a bag of clothes, a bottle of hair oil, a mirror and a comb next to it. A string with clothes hanging on it is hung across the room. A solitary door is the only source of ventilation. Rathore shares the room with seven other labourers who, like him, have left their villages in Uttar Pradesh to work in Sanand, Gujarat’s hottest industrial hub.

Since 2008, when the Tata Nano plant shifted from Singur, West Bengal, to Sanand, this small town 20 km off Ahmedabad has attracted an influx of labourers from Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar. The 15,000 migrant labourers work across automobile units and FMCG factories in the Sanand GIDC (Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation), which only had a few chemical firms before 2008.

Rathore moved to Bol village, 12 km from Sanand, from his village Himayupur in Firozabad district, Uttar Pradesh, three months ago.

Finding a room was the easy part. This village now has several new buildings providing rooms on rent to migrant labourers working at GIDC. Rathore and his roommates together pay Rs 5,000 a month for the room they share in one such two-floor building. Each floor has three rooms, with a common toilet and common kitchen between them.

Rathore is illiterate but a skilled “electric wiring worker”. He learnt how to install electric wiring network in buildings in Firozabad city. His sister and brother-in-law live in Ahmedabad, and it’s through them that he got in touch with a thekedaar, who gave him the job of an electric wire worker at an under-construction automobile ancilllary unit in Sanand. Rathore, whose parents are dead, has four other siblings. Every weekend, he makes it a point to visit his sister in Ahmedabad.

While he has no fixed hours of working, he makes just Rs 100 a day more than what he claimed to back home. But, Rathore justifies, these Rs 400 a day go longer. “There, I would spend it all up. In the comfort of your home and village, you end up spending more,” says Rathore.

He has another reason to be careful with his money. He has to repay the Rs 15,000 he borrowed from his brother-in-law in order to take care of his initial expenses in Bol.

When he does feel like home, home is not too far away. Because of the changing demographics of villages surrounding Sanand, the total Hindi-speaking migrant population (15,000) now exceeds that of the natives (8,000) in Bol, Shiyawada and Motipura villages. New eateries offering spicy North Indian fare have come up and, true to the Gujarati entreprenurial spirit, some CD dealers have begun stacking Bhojpuri movies to cater to migrants from eastern UP and Bihar. One Bol landowner, Dashrath Vaghela, even plans to open a mini-theatre screening Bhojpuri movies.

While he does miss his friends in Uttar Pradesh, and plans to visit them next Holi, Rathore has struck new friendships with other labourers from his home state.

He is still figuring out what he wants to do eventually in his “new homeland” though. “I don’t like the night shifts in my job. If I am unable to sustain, I’ll shift to Ahmedabad and live with my sister. I have also learnt zip repairing from my brother-in-law,” says Rathore.

He likes the roads and infrastructure here too and wants to “settle in Gujarat forever”, he concludes.

“There is little lawlessness compared to my village where extortion and fights would be quite common. Yahan par kisi ke paas ladne ka samay nahin hai (Nobody has the time to fight here).”

‘I go wherever work takes me’

By Arun Sharma

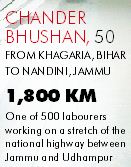

As a boy in Bihar’s Khagaria district, Chander Bhushan was scared of heights. But when he left his village 33 years ago, he found himself building bridges across the country. “Money forces you to overcome every fear,” smiles Bhushan, now 50, and part of a team of around 500 workers employed by AFCONS that’s building eight bridges on the 65-km road between Jammu and Udhampur. The road, which has 43 bridges, eight tunnels and one toll plaza, is part of the project to widen the NH1A between Jammu and Srinagar.

As he lays tarmac on a bridge cutting through the rugged terrains of the Sivalik Hills, he looks 100 feet below, and admits, “I am still a bit scared when I look down from the mountains.”

For the last two-and-a-half years, the under-construction road that falls in Nandini, near Jammu, has been both Bhushan’s place of work and home. Just a few hundred metres away from the site of construction is a makeshift colony constructed by AFCONS: It has 60-70 pucca rooms where the migrant workers, mostly from Bihar, live.

Bhushan lives in one such room, sharing it with seven others. Inside, there is nothing except a steel bed for each occupant. It doesn’t bother Bhushan, as he spends all his waking hours at work. For eight hours of work, he is paid Rs 350 a day. The chill and the high-speed winds notwithstanding, he works an extra four hours every day, earning Rs 43 an hour as overtime.

“How else will I feed my wife and three children?” says Bhushan, who sends Rs 10,000 back home. He visits his village once a year, having last gone there in February. Beaming with pride, he says, “My son passed Class XII in first division, my daughters too have been promoted to Class XII. I want my son to become an engineer.” Bhushan is illiterate but he doesn’t want his children to meet the same fate.

He rings up his family two-three times a day to keep in touch.

However, he didn’t mind coming all the way to Jammu and Kashmir to find work, he says. “I go wherever work takes me”.

The “skilled daily wager” came here for the first time in 2010, working on a railway bridge at Kishanpur, near Udhampur, and then moving on to building a 40-metre-tall bridge near the Nandini Wildlife Sanctuary. Prior to that, he worked at thermal power plants in Gujarat and Karnataka. “A friend of mine told me of projects in Kashmir,” says Bhushan, who hopes to go to Lucknow for a construction project after his current project gets done by next month.

Bhushan also feels a “special connect” with J&K. “When I left home in 1981, my first assignment was the construction of a bridge on river Tawi near Sidhra in Jammu,” he recalls.

At the end of the day, he just “dumps” himself in bed. The roommates run a common kitchen. While the cook has been provided by the employer, they have to purchase their own rations from Nagrota town, 6 km away.

Dinner is when Bhushan and his roommates bond over jokes and gossip. Some huddle in an engineer’s room to watch TV, but it’s only for a short while. They sleep early to get up for next day.

On holidays, they are more relaxed. “We get up late and go to the market in Nagrota in the company’s vehicles. We buy clothes, chappals or rations, or simply hang around,” says Bhushan.

‘Sometimes I think about what I do, and it feels nice’

By Debabrata Mohanty

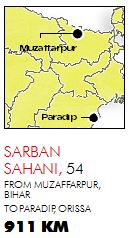

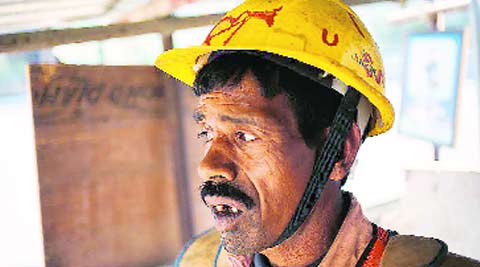

DID he study till Class II, or was it III or IV? Sarban Sahani can no longer remember. All that seems a lifetime ago. The 54-year-old from Muzaffarpur district of Bihar has spent the past 16 years doing thermal and mechanical insulation at oil refineries, fertiliser plants and power plants across the country, from Jamnagar in Gujarat to Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu. That has been his education, Sahani smiles, and one he “knows very well”.

He came to Paradip, a port town in Orissa’s Jagatsinghpur district, two months ago. At the upcoming 15 million tonne per annum refinery of Indian Oil Corporation here — set to be eastern India’s biggest crude oil refinery — Sahani is one of the prized hands among the 15,000-odd labourers. Most of them are from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

Insulation by asbestos and other materials that increases the life of plant machineries is a vital phase of any big plant — steel, power or oil refinery. For the oil refinery at Paradip, insulation is of critical importance as a saline environment corrodes parts faster.

Not many have expertise in insulation work as Sahani in these parts. On the other hand, he — as he points out — can finish the task in less than a month. With the refinery scheduled to go on stream in another three months, Sahani is in high demand.

He earns Rs 312 a day on an average, including overtime. Back home in Muzaffarpur, Sahani has a large family to take care of, including two sons and ageing parents. His three other sons and two daughters are married. The family is landless. While he ensured all his children went to school, only his youngest studied beyond Class X. He is now in college.

Sahani says there is little work to be found in the village. “So I have to go around the country.”

Sitting on a piece of aluminium sheet after having a lunch of roti and a curry of soya chunks, he says he doesn’t mind the extra work, or the extra money. “I have nothing else to do here. So I do overtime.”

Work starts at 8.30 am. “We have to wake up by 4.30 am and start cooking our food. By 7.30 am we have to leave our labour colony for the refinery,” says Sahani. Though work is supposed to get over at 5.30 pm, most labourers have to work extra till 7.30 pm.

Though then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee laid the foundation stone for it in 2004, work on what would be the country’s first zero-residue oil refinery gathered steam only in 2009. It is scheduled to be completed in March 2015, when it will start producing LPG, naphtha, petrol, diesel and sulphur. A Petroleum, Chemicals and Petrochemicals Investment Region is also planned around the refinery, and is expected to kickstart the economy of the area.

Sahani hardly thinks of his work in those terms. But, he admits, “Kabhi kabhi sochke achha lagta hai (Sometimes I feel happy thinking about it).”

In their nearly 12-hour shifts at the factory, workers get a one-hour lunch break. As Sahani and others chat, the conversation invariably drifts to the families back home.

Sahani, who first picked up the skills of the trade at a factory in Kolkata, has worked at the Jamnagar refinery of Reliance, the Mathura oil refinery, the Bina oil refinery, a fertiliser plant in Uttar Pradesh, a power plant in Budge Budge of Kolkata, as well as a fertiliser plant in Paradip. His work requires him moving every six months to a year.

By the time he is back to his living quarters these days, located in a labourer colony around 3 km from the plant, Sahani has barely any energy left other than to have his dinner and collapse into bed. He and his five roommates share a 15×10 ft space, and none of them has a TV.

“I don’t even have a mobile phone. I ask a Bihari roommmate to ring up my family from his mobile,” he says. “What is the point of spending so much on a mobile phone?”

Once his work is done in Paradip, in another two months, Sahani would return to Muzaffarpur. But it would be a short break. “I would sit at home for a few months and then go elsewhere.”

‘I’ll buy my family small things they never had’

By Sreenivas Janyala

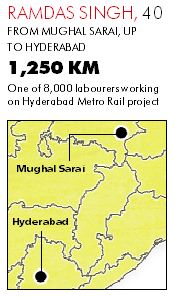

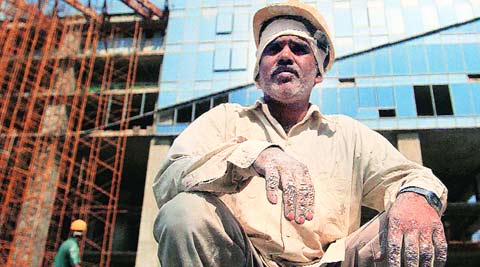

Holi is still more than two months away. But Ramdas Singh, 40, can think of little else.

“For us it does not matter if it is New Year or a public holiday. We all like to go home only for Holi. If I can save Rs 10,000-15,000, I will purchase some new clothes for my wife, children and relatives. The house also needs repairs,” Singh stresses.

Amidst the huge columns and pillars of the Hyderabad Metro Rail project, Singh is easy to miss. But at least he has company. Of the 8,000 workers in distinctive orange vests and trademark helmets at work on the metro, nearly 5,000 are from Bihar, Orissa, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh.

Singh, 40, arrived six months ago from Adhaura village near Mughal Sarai, Uttar Pradesh. A farm labourer, he had no work at the time, and a relative working here as a helper brought him along.

Singh is now one of the helpers laying pillars for the Punjagutta station on the metro line. He likes Hyderabad, he says. “The pay is okay, the city is good, there is plenty of work. I work eight hours, sometimes extra four hours depending on requirement.”

The Hyderabad Metro Rail project is the world’s largest Public Private Partnership Project in the metro sector, with an investment of over Rs 17,000 crore. It will cover around 72 km, and will be integrated with existing railway stations, suburban railway network and bus stations. The first 8-km stretch is scheduled to start functioning from March 21.

Singh has few regrets about having come to Hyderabad. “There is no work in villages and there are too many people dependent on small fields. When I left, there was no work for anyone. Some went to Delhi or Bangalore, I came to Hyderabad.”

His two daughters are married and he no longer has to worry about where money for next month’s rations will come. Instead, he is planning investment in a tractor. “I and my relatives may pool money to buy one to use in our fields or give on rent.”

This time when he goes home on Holi, Singh adds, he may even have enough cash to just hand it out to his daughters, son and wife. “They could purchase the small things they wished for but never could.”

‘It is Mumbai that tends to our family’s every need’

By Shalini Nair

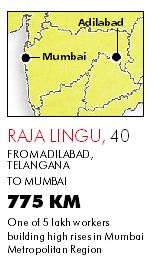

The glass-and-steel facade of India’s tallest commercial tower, Kohinoor Square in Mumbai’s Marathi heartland of Dadar, all 50 floors of it, gleams in the afternoon sun as Raja Lingu polishes the granite flooring.

Lingu is among the newest batch of migrant construction labourers to start working in this erstwhile mill land plot, located just across the street from Shiv Sena Bhavan, the headquarters of a party that has built its base on anti-migrant tirade. Raj Thackeray, the leader of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena that has made an even shriller pitch on the issue, was one of the investors in the plot. He later sold his share.

If Lingu has heard any of this, he knows not to let it bother him as he works on his patch of the Mumbai skyline. The 40-year-old is part of a faceless workforce of 5 lakh-odd construction labourers employed in upcoming high rises in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, a majority of whom are from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.

Lingu has come from Telangana. Two months after it became India’s newest state in June, a drought forced an exodus from his village in Adilabad district on the state’s northernmost tip. Several went to Bangalore and Chennai; Lingu along with a dozen others came to Mumbai.

He landed his job, of a helper to a mason, after waiting endlessly at one of Mumbai’s many labour nakas. After spending frugally, the job leaves him with Rs 8,000 a month, which he sends home to his wife, daughters and aged parents. His eldest daughter, 21, is married, but he is worried about saving enough to marry off his second daughter, who recently turned 18, and to provide for the education of his 15-year-old youngest daughter.

With little money to spare, Lingu lives 30 km to the north of Kohinoor Square in a shanty town that goes by the name ‘Daulat Nagar’. He and seven other labourers share a 100 sq ft hutment there, shelling out Rs 500 a month each as rent.

He doesn’t miss the bigger house in the village as much as the food. They grew their own foodgrains and vegetables, and since he came to Mumbai, Lingu has not experienced that “abundance”. Meals are expensive in the city and irregular.

But while he would like to go back, right now that option is out. The drought meant he earned little this year from the four-acre paddy field that is his family’s sole source of sustenance. “I dug 100 feet deep and still there was no trace of water,” says Lingu.

On the 25th floor of Kohinoor Square works 44-year-old Sandhani Mohammad, who has spent the past 15 years in Mumbai, living away from his wife and children who are back home in Katihar district of Bihar. “Home” in these years has meant one tin-shed to another at the many construction sites where he has worked as a carpenter.

Mohammad says he prefers that to living in the predominantly Muslim slum of Madanpura, where he shares a rented 225 sq ft shanty with 25 to 30 others in the periods he is without work.

Once a year, he makes a visit home, during the harvest season. “Our farm provides just enough foodgrains and vegetables to feed my family. However, it is Mumbai that earns me money to tend to every other need of theirs,” says Mohammad.

Once completed, the top five floors of Kohinoor Square will house a 42-suite seven-star hotel, offering the highest vantage view of Mumbai.

Kohinoor Square has been a work-in-progress since Raj Thackeray along with Sena leader Manohar Joshi’s son Unmesh bought the prime piece of land in 2005 at a record-breaking price of Rs 88 crore an acre. When realty prices went down four years later, Thackeray exited.

The floor Mohammad is working on offers an unhindered 180 degree view of the Arabian Sea and the many buildings dotting Mumbai’s signature cityscape.

Though happy for their toehold in it, Lingu and Mohammad have no delusions about their place in that world or even the interspersing slums. “Once the fields are fertile again, I will go back,” says Lingu.

‘House is just to sleep, eat. We’re here to work’

By Ramendra Singh

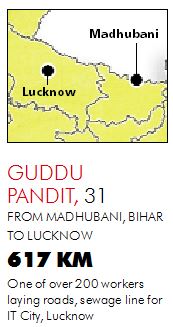

Above him, Lucknow’s first IT City will take shape. Down below, laying pipes for a sewage line, Guddu Pandit admits he doesn’t know what the project is exactly about.

What he does know is that he can’t go wrong in placing even one 5-foot-long pipe on his line. “Each has to be properly fixed in the other so that there is no leakage. Even if one pipe is not placed properly, sewage is affected,” he says.

Pandit, 31, is one of the 50-odd labourers laying the sewage line for the 100-acre IT City coming up on Lucknow-Sultanpur Road, about 15 km from Lucknow city. He heads a team of 11.

Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav laid the foundation stone for the Rs 1,500-crore project in October, promising that it would create 25,000 jobs on completion. While a major chunk of the proposed city will be given to IT and ITeS sector, there will also be a skill development centre as well as a super speciality hospital at the site.

Originally from Laduama village in Bihar’s Madhubani district, Pandit joined his present job in April. While he began as a labourer, he adds, he gradually picked up “the technique of properly laying these pipes”.

His family were originally potters, but by the time Pandit grew up, demand for the goods they made had long evaporated. Pandit left home to find work as a labourer when he was just 19, the same year that he got married. Twelve years on, he earns about Rs 7,000 a month, including overtime.

As he sends most of the money home to his wife, four children, between the ages of 10 and 3, and parents, Pandit lives sparingly. He and three others share a three-room house in Jhiljhilapurwa village, about a kilometre from the IT City site. The rent comes to

Rs 1,000, split equally.

The walls are unplastered, and the house has no furniture, electricity or running water. Food is cooked on firewood they manage to collect. At night, they sleep on beddings spread on the floor.

“Our day starts about 4.30 am. We have to get ready, cook our food, and report for work by 8 am. If the fog is severe, we can reach a bit late but not after 9 am,” says Ram Avtar, Pandit’s colleague and a resident of Sitamarhi district in Bihar.

Once their day’s work is over, Pandit calls his supervisor and gives him a status report on his mobile phone — a battered old thing, held together by a rubber band.

There is little spare time in Pandit’s day, and little by way of “entertainment”. But he doesn’t think much about how they live. “The house is just to sleep and eat. We are here to work.”

Pandit hopes to earn enough to put a cemented roof on all the rooms of his house in Madhubani, and to educate his children. His eldest daughter, 10, studies in Class V at a government school, while sons, 8 and 5, are in LKG and nursery at a convent school in neighbouring Bhagwatipur village.

Pandit pays Rs 500 as fees per month for his sons. His youngest, a three-year-old girl, is still to start school. Pandit doesn’t mind the convent fees as long as the school gives his sons a “better education”. “I will try to make them do something better and not become a labourer like me,” he says.

Pandit visited home last month. He isn’t sure when he will see his family next, probably not for another six months. Come New Year eve, he and his friends will huddle inside their dark home and cook “something besides daal-rice”. “There will be no work at the site and we will make something special, like poori-sabzi. We are all vegetarians, and we don’t drink. That will be our celebration.”

‘We are in a pardesh. We can’t complain’

By Milind Ghatwai

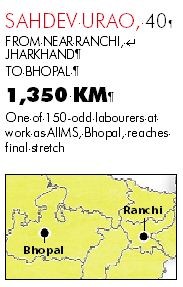

Sahdev Urao is counting the days to when his sons’ summer vacations begin. This time, he hopes to successfully make it back to his village. Last time (two or three years ago, he says), his family of four had to skip the trip as they couldn’t find anyone at the Bhopal railway station to guide them to the right platform. They missed their train, and decided not to go.

“I am illiterate,” Urao admits sheepishly, as his sons tell the story. Anil is 11 and Sumit 7, but both are in Class II. When Urao went for their admission to the government school in Bagh Sevania in Bhopal two years ago, he found it more convenient to put them both in one class. Anil hadn’t been to school till then.

This way the two sons study together, and go to school and come back with one another, while Urao, who is in his late 40s, and wife Malti, who also works as a labourer, are away at work.

They are part of the 150-odd workforce putting the final touches on AIIMS, Bhopal. It was one of the six new AIIMS announced back in 2003, but construction began only a few years ago. Most parts of it are functional, with surgeries to start early next year.

Originally from a small village near Ranchi, Jharkhand, this is the first time Urao is living outside the state. He arrived in Bhopal five years ago, one of the 15-20 workers brought by a contractor. For a 10-hour shift from 8 am to 6 pm, Urao earns Rs 150 a day. His wife gets Rs 10 lesser.

The family lives in a tin-roof shanty next to the work site, in one of the two settlements housing labourers working at AIIMS. Almost all the space inside is taken up by clothes and children’s books. They bathe in the open, and animals have a free run of the place. In a nearby hut is a common TV set, shared by all the labourers.

The 14X8 ft accommodation is much smaller than the home Urao has in his village, or the other houses he has occupied since he came to Bhopal. Looking at the buildings around that make his own shanty seem even smaller, Urao says he can’t complain.

Back home, the joint family together owns a small plot of land on which they grow rice. Urao says they could barely make ends meet, and ate only rice at all times. Now, he beams, his family has started having chapatis at night, for which he buys flour at Rs 20 a kg.

Their shanty has an electricity connection but the supply is cut off between 8 am and 5 pm, when the labourers are expected to be at work. Urao has no complaints about that either. “We are in a pardesh (foreign land). We can’t complain about such little things… Maybe they want to protect our belongings from an accidental fire in our absence.”

Urao’s day though begins much before 8 am, when he leaves home while it’s still dark to try collect firewood from an abandoned plot nearby. What he collects depends on the guards around. On the days he runs into them, they have to do without fire to keep the house warm or to cook food.

A perplexed look on his face, Urao looks at his calloused hands and, pointing to the hospital building, says: “We are here to build AIIMS for the public. Why should we be stopped from collecting firewood?”

Most days, he is too tired to watch anything on TV, and the family can’t spare enough money to celebrate all festivals. They make do with only Chhath Puja. Trips to the village are rare.

Urao expects to leave Bhopal after construction ends in the coming months, and is not sure where the labour contractor will send him next.

Chances are he will never use the apex hospital he is helping build. Once, he recalls, he had found it difficult to get son Anil treated at AIIMS, Bhopal, after he fractured his hand.

Like most migrants, Urao has no identity proof to show he is BPL, needed to receive treatment at the hospital. Urao took him to a private hospital, which asked for Rs 12,000. Finally Anil was treated at a government hospital. Urao fears his hand was not set right and he still has difficulty lifting heavy things. The irony does not escape Urao. “We have done our bit to build AIIMS, but can’t get treatment there for want of an identity proof.”

‘I long to watch Hindi movies, 2-3 a month’

By Shaju Philip

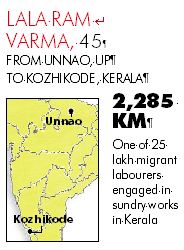

At a local school ground in Kozhikode, a pandal is being erected for the week-long 55th Kerala School Youth Festival, billed as Asia’s largest youth fair, starting January 15. Amid the web of tall poles raised for the pandal, and the men scrambling up and down them, Lala Ram Verma dreams a dream. Every time he hauls a pole at the pandal, he takes a step closer to a two-room brick house he wishes for in his village Lala Kheda in Uttar Pradesh.

It’s the second time in two years that Varma, 45, is in Kerala from the village in Unnao district for work. “My brother-in-law has been working here for 10 years as a construction worker. With his help, I managed to find job with a pandal contractor,” he says. November marks the start of a season of major public functions in the state, boosting the demand for pandals.

In his village, where his wife and two daughters and a son stay, he has two acres of land. When he is not working as a labourer, he tends to his farm. His children are all in school.

It was in 1995 that he first left Lala Kheda seeking work. “For nearly 20 years, I worked as a porter in Lucknow. It was a meagre, unstable income,” says Varma. When he decided to look out, Kerala was his first choice.

Varma now earns around Rs 500 a day, and manages to send home Rs 12,000 a month to his wife. The couple try and restrict their expenses to Rs 2,000 a month, to save the rest. Having dropped out of school after Class VI following a spat with his father, Varma is determined to ensure his children complete at least graduation.

A government-assigned study found in 2012 that there were around 25 lakh migrant workers in Kerala, mainly from the North and Northeast. Every year, it is estimated, 2.35 lakh workers come to Kerala.

While he has a single-room accommodation at Cheruthuruthi in Thrissur, Varma moves from place to place depending on work. “There, I along with six other north Indian workers camp at location,” he says.

Once work is done, the seven spend their evenings listening to Hindi film songs on a mobile phone. They long to see Hindi films, but it’s rare to find one playing in theatres. When they are lucky, Varma says, “I watch two-three movies a month.”

He likes Kerala though, but won’t settle down here. “Language is the main barrier. I will work in Kerala till my health permits,” he says.

He will also take back from here his dream of a home. He always wonders at the size of houses in Kerala, Varma says. “I want to renovate my home… a new room, a new kitchen.”

‘There’s nothing in the village’

By Rakhi Jagga

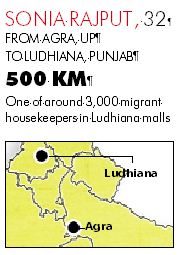

It’s 9 am and the showrooms are still to open at MBD Neopolis, a popular mall in the post part of Ludhiana. The city is still half-asleep on a winter morning. Sonia Rajput, though, has turned out in a crisp green salwar kameez and black sweater. Applying a dark red lipstick, the 32-year-old says, “It’s Christmas. We too have been told to match the mood of the mall.”

Rajput is part of the housekeeping team at MBD Neopolis that works from 9 am to 5 pm. Over half of them are migrants, mostly from UP and Bihar. A year ago, she had walked into the mall with “very little confidence”, Rajput says. “I had never been to a mall and was overwhelmed.”

She had just moved to the city then from Banpur village in Agra,UP, with her two children, 4 and 2, to join her husband, who works as a daily wager. For the first five months, the Class VIII pass stayed at home, before taking up work as a domestic help, earning Rs 2,000 a month.

Then a friend of her husband told her about the MBD Neopolis job. It could mean more than three times the pay, apart from other benefits like a PF account and fixed number of paid leaves.

After the initial “tremor” of seeing “such a large” public space, Rajput’s confidence further plunged at the sight of modern floor cleaning machines. A week’s training made her realise that “machines only look scary, but are much easier to work with”. She can now speak simple English sentences. “Every week, we are trained in etiquette,” she says.

For Rajput, working at the mall has not just meant an increase in income, but a huge leap in confidence. “I had never even been to Agra. Now, far away in this city, I have made friends. We watch movies together and shop at stores. Of course, not this one as is it is too expensive.” So, does she miss her village? “Not at all. There was nothing there.”

‘I wish I can get family to Kashmir one day’

By Mir Ehsan

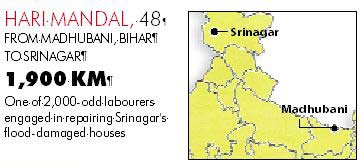

Temperatures are now hovering below -1 degrees Celsius, but Hari Mandal doesn’t mind the cold. His head warmly wrapped in a woollen cap and a muffler, he wields his trowel carefully as he lays cement on the damaged brick wall of a house in Srinagar’s Jawahar Nagar colony.

Back home in Darhara Mahadev Mand village in Bihar’s Madhubani district, it is a comfortable 20 degrees Celsius at daytime. But, as Mandal says, that’s hardly a consideration. “It is very difficult to work for 10 hours under the sun and get only Rs 200 or 250 everyday. In Kashmir, we work comfortably and earn well too.”

These days are particularly good. Mandal is among the 2,000-odd labourers engaged in rebuilding houses damaged in Srinagar in the September floods. “When I first came to Kashmir in 1986, I would earn Rs 20 or 30 every day. Now I can earn up to Rs 500. After the floods, the rates have surged to Rs 600-650 every day,” he says.

It’s the Rs 8,000-9,000 he can save and send home that has kept bringing Mandal back to Srinagar year after year, spending at least nine months here each time. His BPL family recently purchased a TV and a fridge, the 48-year-old says proudly.

The J&K Labour Department estimates that more than one lakh workers from different states come to Kashmir in the summers looking for work. Most of them leave in winter.

Mandal says the one-room rented accommodation he shares with five others at Mehjoor Nagar too had got inundated in the floods. He wanted to leave like the others but the thought of his daughter’s wedding next year held him back. “We are landless peasants. The family looks forward to my money parcel,” he says.

He has five children, between the ages of 18 and two, two of them daughters. Having never gone to school himself, he wants to ensure they receive proper education. “I want them to become government employees and not labourers,” he says. “Otherwise they too will have to work hundreds of miles from home.”

As he cracks jokes with fellow workers, Mandal admits he has few friends in Kashmir apart from this small circle from Bihar. In 28 years, he has picked up only a few Kashmiri words but can’t speak the language.

With days off a luxury, he has not even visited any of Srinagar’s famed tourist spots so far. “I saw the Mughal Gardens and Dal Lake from a distance recently,” he says.

Mandal hopes though to do one day all the things the hundreds of tourists he runs into do here, with his family. “I wish I can bring them here once in my lifetime. But it requires a lot of money.”

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05