OPINION:

Winsor McCay is widely regarded as one of America’s greatest cartoonists. His early 20th century comic strips (“Little Sammy Sneeze,” “Dream of the Rarebit Fiend”) and animated shorts (“Gertie the Dinosaur,” “The Sinking of the Lusitania”) are still among the most groundbreaking examples of both genres.

What McCay is best known for is his comic strip masterpiece, “Little Nemo in Slumberland.” The enthralling tale of a boy’s dreams, fantasies and magical adventures was a Sunday funnies staple in many households. Brilliantly drawn and colored, it ran on a weekly basis in two high-circulation newspapers from 1905 to 1927.

Words such as “genius” have been used to describe McCay’s work, including by comics historian Robert C. Harvey. Meanwhile, arts and culture journalist Jeet Heer made this assessment in the spring 2006 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review: “In the history of comics McCay was the great pathfinder, the early scout who marked the trails that others would follow. If not the greatest of cartoonists, he has a uniquely pivotal role in the history of the form.”

Unlike most older comic strips, the general public is aware of Little Nemo. Notable collections were put together by Richard Marschall, Checker BPG, Fantagraphics and Evergreen/Taschen. John Canemaker’s biography of McCay still stands the test of time. An animated film, “Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland” (1989), has maintained its fan base. Earlier this year, Eric Shanower and Gabriel Rodriguez released a well-received IDW comic book series, “Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland.”

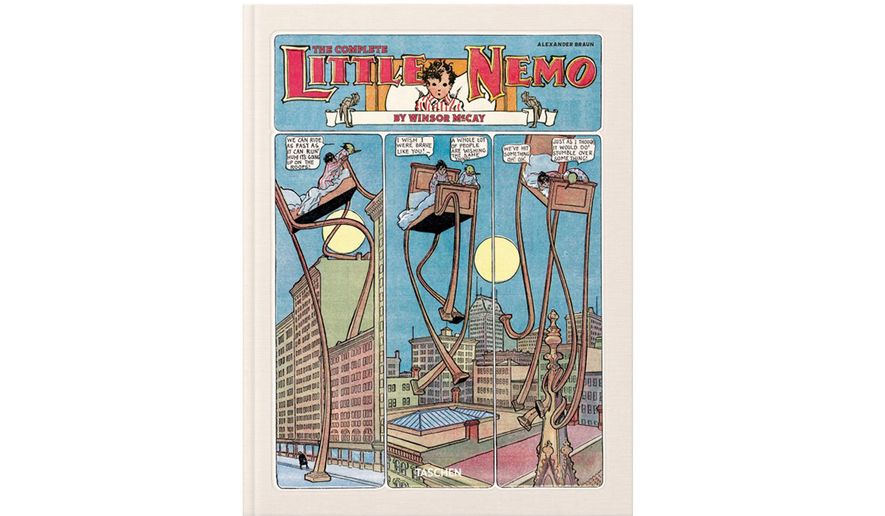

Visual artist Alexander Braun — and the successful German art book publisher Taschen — has just achieved the coup de grace. His new collection, “Winsor McCay: The Complete Little Nemo,” puts together, for the first time, the influential strip’s entire print run. This massive two-volume set comes in a cardboard carrying case (with a handle) and, as a word of warning, costs a pretty penny.

The first volume is a hardcover edition containing all 549 strips. The original run of “Little Nemo in Slumberland” appeared in The New York Herald from 1905 to 1911. It was followed by the 1911-1914 period in the New York American-Examiner (retitled “In the Land of Wonderful Dreams” because of copyright issues), and an unsuccessful return to The Herald (with its original title) from 1924 to 1927.

McCay was an exceedingly talented cartoonist. He had an imaginative Art Nouveau technique that enabled him to combine stunning images, architectural marvels and vivid colors. His great precision to detail could be witnessed in every scene, building, animal or fantasy character and contraption he dreamed up for Slumberland. With only a few exceptions (Johnny Gruelle, R.F. Outcault, Lyonel Feininger), no other cartoonist of McCay’s era matched up to his artistic skill set.

If there was one true weakness to McCay’s career, I’d say it was his writing style. Nemo’s adventures with his regular companions, the green-skinned, cigar-toting clown Flip and the ever-silent Jungle Imp, are easy enough to follow. Alas, the dialogue in the weekly dreams tend to play a supporting role. While there are occasional glimmers of literary prose and striking humor in the early strips, it’s almost nonexistent at the end.

The second volume is a softcover edition examining McCay’s life and work. To Mr. Braun’s credit, he has written an intellectually stimulating account (in the style of newspaper pages) of what makes this particular cartoonist stand out above others.

For instance, he notes the “similarities between McCay’s fantasy world on paper and the real attractions of the time are much more fundamental and symbiotic.” He believes it wasn’t “until McCay established a connection with his readers’ actual (entertainment) experiences that his dreamland became a true reflection of the state of American society at the turn of the 20th century and an accurate portrait of the times.”

Mr. Braun also posits this analysis: “McCay stretched the possibilities of Slumberland to a point that allowed him to do almost anything.” There has been some debate about McCay’s actual state of mind when drawing Little Nemo. Yet the author points out this fantasy world would “resemble effects seen in the illusion rooms and fun-house mirrors found at any good amusement park.” Be it a walking bed, mystical creature or giant insect or animal, “[d]reams know no boundaries” in Slumberland.

Without hesitation, I’d call “The Complete Little Nemo” one of the most visually stunning examples you’ll likely ever see about a comic strip of this magnitude. Thanks to Alexander Braun and Taschen’s efforts, Nemo’s magical dreams can now be read and shared for generations to come.

• Michael Taube is a contributor to The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.