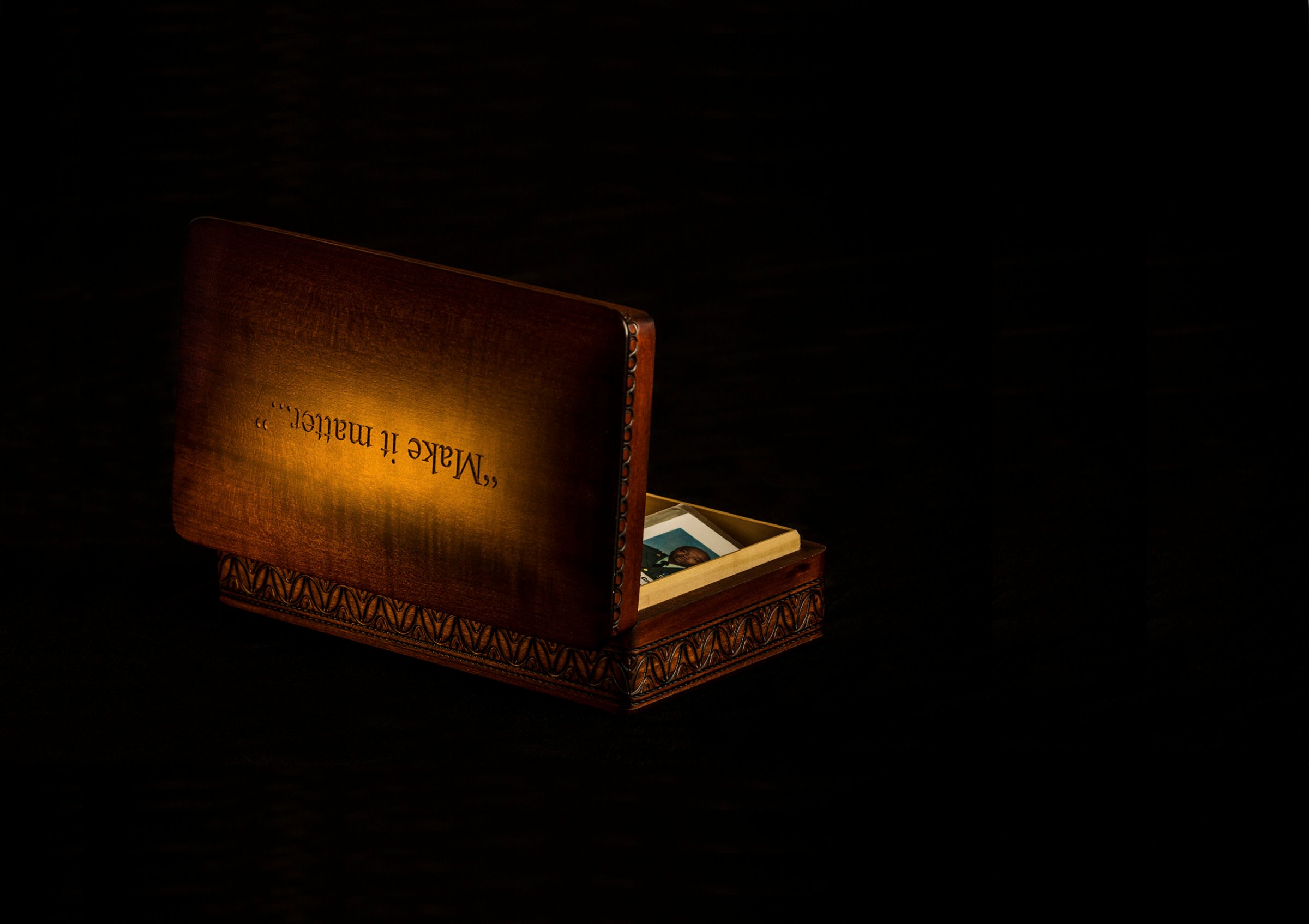

A handsome carved box sits atop the desk where Army General Martin Dempsey works and waits for a call from the White House to send young Americans to war in Iraq again. It’s actually a custom cigar box a fellow officer bought for him in Virginia Beach after they returned from Iraq in 2004. But inside, arrayed a little bit like tea bags at a fancy restaurant, sit 133 laminated cards, each one picturing a soldier who died under Dempsey’s command in and around Baghdad a decade ago. MAKE IT MATTER–the words carved into the top of the box–are a warning to Dempsey, now the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Urging a President to send troops into combat is “always the hardest decision,” the nation’s top uniformed officer told military families in July. “You just can’t escape it, but more important, you should not try to escape it.”

Lately, Dempsey hasn’t sounded like he wants to escape it. Instead, he seems to be saying it’s not if but when GIs will again be fighting on Iraqi soil. Ever since President Obama began bombing terrorists in Iraq in August, Dempsey has been warning that limited numbers of U.S. ground troops–perhaps hundreds–will probably be required there as the stakes rise in the battle against the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). With incoming Defense Secretary Ashton Carter more manager than warrior–Carter has no time in uniform–Dempsey stands alone as strategist. “This is my third shot at Iraq,” Dempsey said on Nov. 19, shortly after returning from a reconnoitering mission there. Baghdad’s new leaders, he said, are “going to need a combination of courage, luck and leadership to manage their way through this.”

And, he added, American help.

It’s America’s third shot at Iraq too, and the prospect for this round looks no better than the second. More than 30 nations have been battling ISIS for a half year without regaining much territory. About a dozen nations are conducting air strikes, with the rest training Iraqi forces. Some 3,000 U.S. troops are earmarked for the effort but barred from ground combat so far, which means they spend their time advising and training Iraqi troops.

For much of the fall, Dempsey has been arguing that more U.S. firepower will probably be needed. He shook up the White House for the first time in September, barely a month after U.S. air strikes began hitting ISIS targets in Iraq. He declared, in a prepared statement before Congress, that he wouldn’t hesitate to urge Obama to send in ground troops to “accompany Iraq troops on attacks against specific [ISIS] targets.” Generals routinely refuse to discuss what they term “hypotheticals,” yet Dempsey did just that, without prodding from any lawmaker. The White House was not pleased, retorting that U.S. policy “has not changed.”

Dempsey did it again the same month. “I’ve never said, ‘No boots on the ground,'” he told a Notre Dame audience. “I don’t use any language that boxes me in.” Unlike the Commander in Chief, he seemed to be saying.

The Chairman can sometimes be too clever. “We don’t debate anything in the military,” he has told Congress. “We provide options and let our elected officials make their decisions.” But while speaking to lawmakers in November, Dempsey suggested that “a low-risk option for the campaign would probably include the introduction of U.S. ground forces to take control of the fight.” The Pentagon brass, he quickly added, doesn’t “believe that’s the right thing to do at this point.”

But nearly everyone at the Pentagon thinks it might be the right thing to do soon. As lethal as U.S. airpower can be, it’s far deadlier–and more accurate–when there are U.S. troops on the front lines, weighing ever changing intelligence and guiding air strikes to specific, U.S.-confirmed targets. And so the most benevolent interpretation of what Dempsey has been doing is preparing the President for his military’s recommendation for reinforcements on the ground when the fight to retake Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, begins. That date keeps shifting, but it’s likely to happen by mid-2015. “Dempsey’s pretty savvy,” says retired general John Keane, who served as the Army’s No. 2 officer. “Because he has to provide his own personal opinion to Congress, he takes license to really get his views out there.”

“THE ANTI-PETRAEUS”

Dempsey is a little different from some of the other four-star generals of the 21st century. He shuns honorary degrees, late-night television appearances and cooperation with articles like this one. Aides call him “the anti-Petraeus,” a dig at David Petraeus, the retired Army general who cultivated–and got–fawning press coverage. Dempsey’s low-key style is designed to increase his clout at the no-drama White House.

A New Jersey native, West Point graduate and amateur crooner who married his high school sweetheart, he is also an armor officer by training. Dempsey helped command a tank brigade in the first Gulf War and led the 1st Armored Division in Baghdad in 2003 and 2004. As the Iraqi capital exploded following the U.S. invasion, he transformed his heavy division into a counterinsurgency force that calmed the Shi’ite revolt and won praise from colleagues. He would go on to train both U.S. and Iraqi troops and do a stint at U.S. Central Command for seven months in 2008 with only three stars on his shoulder after his predecessor, Admiral William Fallon, stepped down early following an impolitic interview about the chances of war between the U.S. and Iran.

These successes led Obama to tap him as the Army’s top officer in 2011. Still, he was stunned, the day after taking over as the Army chief of staff, when Defense Secretary Robert Gates told him he’d be nominated to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

Since then, Dempsey’s been a steadying hand at the Pentagon as he enters the final year of his four-year tour as Chairman. But the debate about ISIS is looming, which will test Dempsey’s relations with the White House. “Disagreement isn’t disloyalty,” Dempsey has said, although it’s possible to see how the White House might take it that way. In fact, adding to his independent stature, Dempsey has tacitly criticized the President for not fighting harder to keep U.S. troops in Iraq after 2011. Many military officers believe a lingering presence would have kept ISIS out of the country and preserved the gains that cost the U.S. more than $1 trillion and 4,491 lives. The Obama Administration said it had to pull them out after the Iraqi parliament refused to grant legal immunity to U.S. troops beginning in 2012; others argue Obama was eager to bring all the troops home and didn’t fight hard enough to keep a residual force behind. “There is a debate, in which I am not a participant, about whether we tried as hard as we could to leave [some residual force] there,” Dempsey has said, diplomatically. “I thought we should have left forces there.”

THE CHAIRMAN’S WAR PLAN

How soon might more troops go? Dempsey has hedged his bets so far, endorsing an air war that has halted ISIS’s advances but done little to retake the wide swath of Syria and Iraq that ISIS now occupies. The real test will come when Iraqi forces are ordered to retake Mosul, in the northern part of the country.

Military realists argue that if the U.S. and its Iraqi ally have any hope of defeating ISIS on the ground, a limited number of American troops, to suss out intelligence and call in air strikes, will be needed. An initial deployment would range from dozens to hundreds, but some in the military could eventually push for thousands. “Obama has tied the military’s hands by saying no U.S. ground troops and turned it into an open-ended conflict like Vietnam,” says Gary Anderson, a retired Marine colonel. “Our allies know it can’t be done, and our enemies know it can’t be done. Who the hell do we think we’re fooling?”

Politics will play a role, of course. While Dempsey’s objectives can be measured on the battlefield, Obama finds himself weighing a different set of pressures, including his own legacy. The President started his second term declaring that “a decade of war is now ending.” He announced the current military campaign by pledging, “We will not get dragged into another ground war,” a welcome relief to most Americans weary of conflict. But he also recently sent his Secretary of State, John Kerry, to ask Congress not to bar ground troops in a new war authorization. So far, Obama has set a high bar: if ISIS gets “possession of a nuclear weapon,” Obama said Nov. 16 in Australia, that would trigger an order to send ground troops in to secure it.

Dempsey has said he is “certainly considering” recommending to Obama that some U.S. ground troops help the Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga forces retake Mosul, which has been living under a brutal and extreme version of Shari’a since ISIS overran it in June. But, Dempsey insists, the U.S. military would only be supporting Iraqi forces, who would do most of the fighting. Americans have heard that before. “This is going to require a much larger commitment of ground troops down the road,” says Peter Chiarelli, who retired as the Army’s No. 2 officer in 2012 and knows the Chairman well. “I have full confidence that Marty Dempsey will make that argument when the time is right.”

But even if the U.S. somehow helps to drive ISIS militants from Iraq, that still leaves the bigger challenge of destroying them inside Syria, where there is no existing ground force allied with U.S. airpower. The Pentagon wants to train 15,000 rebel Syrians within the next three years and then trust them to focus on defeating ISIS instead of their bitter foe, Syrian dictator Bashar Assad, whose three-year-old civil war has killed more than 200,000.

That separate, even-more-complicated war plan remains a work in progress, Dempsey conceded Nov. 13: “Our priority is in Iraq, and then we will figure out, while disrupting in Syria, what to do about it in Syria.” Whatever Dempsey decides to do, he won’t be making that decision by himself. He’ll be guided by those 133 soldiers sitting silently in that box on his desk.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com