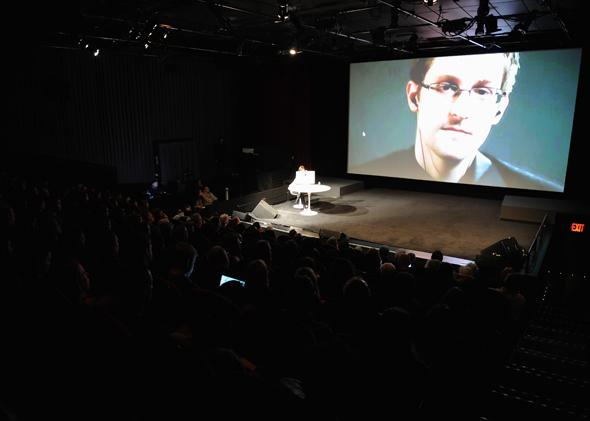

Until very recently, much of the U.S. debate in the wake of the June 2013 Snowden disclosures has focused on the privacy and civil liberties questions raised by the bulk collection practices of the National Security Agency. But foreign leaders have also reacted negatively (to say the least) to the idea that the NSA and other non-U.S. intelligence agencies have access to communications networks and devices all over the world. In response, some policymakers across Europe and in other parts of the world have been exploring a variety of ways to fortify their communications, ostensibly to protect against foreign surveillance.

But they’re doing it wrong. For the most part, policymakers have focused on the physical location of data, an ineffective security strategy given the technical capabilities and widespread information sharing among intelligence agencies around the world. Instead, we should focus on how data is transmitted and stored: namely, by increasing the use of strong encryption.

A recent study from New America’s Open Technology Institute and the Global Public Policy Institute examines the wide range of proposals that originated in Europe over the past year and how they could impact the free and open Internet. (Disclaimer: Robert Morgus is a co-author of the report, and Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University.) Many of the post-Snowden proposals, as it turns out, miss the point—they either don’t address the foreign surveillance problem or might lead to Internet fragmentation. Some aim to keep Internet traffic out of the U.S., like the proposals from parts of Europe and India to route traffic internally, or Brazil’s push to bypass the U.S. and U.K. by building new undersea cables for international traffic. Others focus on keeping citizens’ data stored locally, often through laws that would require foreign companies to maintain local data centers or make it considerably more expensive to store data outside the country. As numerous experts have pointed out, however, some of these proposals could fundamentally alter the current architecture of the Internet, leading to inefficiency and network fragmentation—and, in all likelihood, not actually achieving the goal of thwarting intelligence agencies.

But the post-Snowden backlash has also led to some improvements. Another potential solution—promoted largely by academics and technologists—is to expand the use of encryption for different services, from email and mobile messaging to the transmission of Internet traffic more broadly. Although they have not gotten as much attention, a range of different encryption proposals have surfaced, especially in Europe, since the Snowden disclosures began. At the same time, American tech companies have started adding more encryption to their products, a constructive response to concerns expressed by both individual and enterprise customers about the security of their data, as well as increasing pressure from advocacy groups.

Around the anniversary of the first Snowden revelations this June, for example, Google released the source code for the Chrome browser’s End-to-End extension, which would allow users to encrypt their data before it leaves the browser. Releasing the source code is a common practice in the computer security community and will allow audits to ensure that the product is secure before Google adds it to the Chrome store. The ultimate goal, according to the announcement, is to develop an easier-to-use alternative to existing end-to-end encryption tools like PGP and GnuGP, which can be difficult and time-consuming even for the most technologically savvy users.

On the device side, Apple announced in September that it would be offering default encryption for its mobile devices—a move that cryptography experts have applauded as a long-overdue step to address a “serious security vulnerability” in the iPhone design. Google followed shortly thereafter with a similar announcement about the new Android operating system And just a few weeks ago, the popular mobile chat app WhatsApp began encrypting its message traffic end to end, which represents “the world’s largest-ever implementation of this standard of encryption in a messaging service.” WhatsApp has over 600 million monthly active users, the majority of whom are located outside the U.S.

Changes of this nature are not new, of course—if you look at the history of the development of Gmail, for example, since 2008 the company has been gradually moving toward greater use of encryption as the data travels between users. But the trend has broadened and accelerated in the past year and a half, and the norms are starting to shift. In March of this year, for example, Google announced that it was taking additional steps to make the more secure HTTPS protocol the default for all traffic and encrypt data moving between internal Google data centers. The combination of the presence of more accessible encryption tools and broader awareness of the issue is clearly producing results: The number of online users encrypting their traffic has quadrupled in both Latin America and Europe since 2013.

What distinguishes encryption from proposals to alter traffic routing or require local data storage is that it focuses not on where data is sent and stored, but how it is transmitted. Encryption actually does protect individual users’ data from unwanted snooping and strengthens the overall security of the Internet.

Unfortunately, the move toward more encryption has created a backlash of its own. The loudest critics have been law enforcement advocates here in the U.S., who argue that encryption will exacerbate the “going dark” problem and prevent investigators from getting access to vital communications. FBI Director James Comey has publicly blasted encryption on numerous occasions, arguing after the Google and Apple announcements in September that the companies’ decisions would place smartphone users “beyond the law.” He later hinted that Congress may need to take action to ensure that law enforcement can still get what they need. Cyrus Vance, the Manhattan district attorney, went so far as to suggest that “the unintended victors will ultimately be criminals.” Similar reactions and debates are also sprouting up in the counterterrorism and national security communities, and new evidence suggests that the government may also be trying to use an obscure 18th-century law known as the All Writs Act to compel device manufacturers to assist in specific investigations.

While not necessarily surprising, the reaction from law enforcement officials is counterproductive and misleading. Aside from the fact that encryption is good for user privacy and the protection of online data, the counterproposals are bad from a broader security perspective. Preserving law enforcement’s ability to access encrypted communications would require building “backdoors” into products and services, meaning that the government would have access to either the encryption keys or a vulnerability that would allow it to intercept and read private communications. Both options come with serious security risks. If there’s a hole in the code, it doesn’t matter whom it’s intended for—anyone could find and exploit it.

That’s why when the Washington Post’s editorial board suggested in October that Apple and Google could employ their “wizardry” to create a “secure golden key” that would be used to access information stored on a device only once a warrant had been obtained, security experts rightly pointed out that such magic was technically impossible. Other recent attempts to require that Internet companies build in wiretapping capabilities for law enforcement have been thoroughly debunked by members of the technical community—who also point out that, despite concerns about “going dark,” the FBI actually has more access to individual communications data now than it ever has in the past. Privacy advocates and technologists are also likely to support a pair of recent bills introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden and Rep. Zoe Lofgren to prohibit government-mandated backdoors or security vulnerabilities. Earlier this summer, the House approved a similar amendment with overwhelming bipartisan support, though it ultimately did not make it into the final spending bill.

In fact, policymakers, technologists, and the public already fought this battle in the 1990s, during the so-called Crypto Wars. The debate at the time was about whether U.S. tech companies should be compelled to adopt a technology called the Clipper Chip that would allow the government to decrypt private communications. Ultimately, the proposal was abandoned as policymakers and privacy advocates reached consensus that commercial encryption should not be deliberately weakened to enable government snooping. The resolution paved the way for the rise in the use of encryption in a variety of commercial technologies, many of which we rely on today to protect our most sensitive communications.

In the end, one of the longest-lasting and most productive outcomes of the Snowden disclosures may be the increased focus on encryption. But, as the recent study from New America and GPPi points out, these proposals are not necessarily getting the attention that they deserve from policymakers—and when they do, it may be adversarial, as we’ve seen in the U.S. It’s time to stop focusing on counterproductive measures and start talking about how to improve the security of the Internet as a whole.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.