A Different Drummer: Getting inside the mind of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

In honor of Sports Illustrated's 60th anniversary, SI.com is republishing 60 of the best stories to appear in the magazine. Today's selection is "A Different Drummer," by John Papanek, which was originally published in the March 31, 1980 issue.

After years of moody introspection, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is coming out of his shell. But whether at home or on a basketball court or in a roller disco, he still steps to the music he hears.

It happened on a perfectly beautiful Southern California afternoon following nine straight days of devastating mid-February rains. Nearly 16,000 Los Angelenos went indoors--and on a Sunday, no less--to watch a basketball game. Moreover, it was a game between the Lakers and the Houston Rockets, which lets you know straight off that it wasn't a particularly big one, except that playoff time was near and it had been many years since the Lakers were fun to watch.

The P.A. announcer for The Forum, Larry McKay, was informing the crowd that the great Laker center, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, had called in sick with migraines. No one booed. In other years the fans would have hooted the roof off the Fabulous Forum and a dozen beach-bound Mercedes would have piled up at a parking-lot exit. Some sportswriters, with wicked glee, would have seized the opportunity to blast a favorite target for showing once more that he cared for nothing and no one except himself. And at least one would have begun typing: "The Lakers' 16-game home winning streak came to a s-Kareeming halt yesterday because Kareem Abdul-Jabbar rolled over in bed and said, `Not today. I have a headache.'"

But no one wrote anything of the sort. On this Sunday afternoon the working-stiff Lakers, without their leader, slopped through two and a half periods, somehow staying barely ahead of Houston. Then a second remarkable thing happened. The crowd suddenly went berserk. Standing ovation. Players on the floor froze in mid-fast break. Abdul-Jabbar had arrived. He had tried to sneak to the bench inconspicuously, an attempt foredoomed by his 7' 2" height. (Officially he is 7' 2"; his lady friend Cheryl Pistono says he is closer to 7' 5".)

Abdul-Jabbar entered the game immediately and swatted five Rocket shots out of the air. He rebounded ferociously, passed with elan and hit six of the seven shots he took, two of them "sky hooks" over Moses Malone, who a year earlier had seemed ready to end Abdul-Jabbar's 10-year reign as the most dominant player in the sport. Of course the Lakers won. The score was 110-102.

"I knew it was too good to be true," moaned Houston Coach Del Harris. "Bringing in Kareem is like wheeling out nuclear weapons."

"Is Kareem better than Malone?" the Rockets' Rick Barry was asked. "What kind of ridiculous question is that?" Barry said. "Kareem is probably the best athlete in the world."

The fans at The Forum wouldn't have disagreed. Their Lakers were about to overtake Seattle, and they were considered the No. 1 contender to unseat the defending champions because, at 32, Abdul-Jabbar was playing like a kid again, having his finest season in five as a Laker. He was playing with vitality and emotion, leading fast breaks, dunking with authority, slapping palms and occasionally--you could be sure because he had finally gotten rid of those infernal goggles after four years--smiling. And he had not missed a single game.

SI 60 Q&A: John Papanek, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and all that jazz

In the Lakers' dressing room Abdul-Jabbar sat in front of his locker. Usually he is in the shower before the press arrives, dresses before he is totally dry and dashes out, saying as little as possible, as though he has a bus to catch. This day he sat there, and the media people approached him as they always do--verrry carefully.

Someone asked him how he felt, and he began to answer. In an instant he was mobbed.

"I haven't had a migraine bad enough to make me miss a game in two years," he was saying. "They're a mystery of medical science. No one knows what causes them. The pain was so bad this morning, I was crying. I couldn't move. I had to lie in a dark room in total silence. You know what it felt like? It felt like the Alien was inside my head, trying to get out my eyes."

The image was clear enough even to those who had not seen the movie Alien. He was asked why, with all the pain, had he bothered with such an unimportant game? Abdul-Jabbar seemed to expect the question. If anything about him has been constant throughout his career, it has been his pride. "These guys are my teammates," he said. "But they are also my friends. They needed me."

Those familiar with Abdul-Jabbar knew there had been migraines before, usually in times of extreme tension. There had been bad ones in 1973, while he was playing for Milwaukee. They developed after seven people -- a friend and six relatives of Abdul-Jabbar's Muslim mentor, Khalifa Hamaass Abdul Khaalis, members of a group called the Hanafi -- were murdered, allegedly by rival Black Muslims, in a Washington, D.C. house that Kareem had purchased for them. Abdul-Jabbar was thought to be a target as well, and he was accompanied by a bodyguard for several weeks. The immobilizing headaches came on again in 1977, after Khaalis and his Hanafi group sought revenge by invading three Washington buildings, including the national head-quarters of B'nai B'rith. They held 132 hostages for 38 hours, leaving seven wounded and one dead. Khaalis went to jail, and the Jewish Defense League threatened to kidnap Abdul-Jabbar. This latest series of headaches--and more would follow--seemed to coincide with Abdul-Jabbar's pending divorce suit.

There are those who have always believed that a man who can dunk a basketball without leaving his feet should be the NBA's Most Valuable Player by default. Because size seems to be the primary requisite for getting the award--centers have won it 19 times in the 24 years it has been given, including Abdul-Jabbar in 1971, '72, '74, '76 and '77--the distinction isn't esteemed as highly as MVP honors in other sports. Maybe that is why smaller players--Cousy, Robertson, West, Baylor, Frazier, Erving, Havlicek, et al.--are accorded greater devotion than the giants who have played the game--Russell, Chamberlain, Abdul-Jabbar, Walton. They are expected to dominate.

Bill Russell, of course, was the perennial champion, the quintessentially unselfish team player/philosopher with the twinkly eyes and the thunderous laugh. Dominant though he was, you had to love Russell. Wilt Chamberlain, of imposing size and strength, once scored 100 points in a single game and averaged 50.4 in one season. But he was a colossus who evoked little affection. Bill Walton, one of the best all-round centers in history, has been beset by injuries; giants aren't supposed to be fragile.

• SI 60: Read every story and interview in the collection

And then there is Abdul-Jabbar, the first, the only player to incorporate every desirable element of the modern game into his own. He has the speed and grace of Baylor, the skill and finesse of West, the size and very nearly the strength of Chamberlain. He is a superb shot-blocker and a better passer than some think; he has seldom had teammates worth passing to. And he has been amazingly consistent, averaging nearly 30 points and 14 rebounds a game during his career. He has constantly been harassed by defenses, often by two opponents. Perhaps he has made what he does look too easy. He is not often "spectacular." But it is astounding how often he gets a "quiet" 32 points.

"He's always been my idol," says San Diego's Walton. "To me, he's the greatest."

"He does things to you that make you ask, `Damn, now how could a man his size have done something like that?'" says Milwaukee's Bob Lanier.

A good bet to top off this, his 11th season, with his second championship ring, Abdul-Jabbar is also likely to accomplish what only one other professional athlete in any sport has done before him--win his sixth Most Valuable Player award. (Gordie Howe had six in hockey.) In pro basketball Russell won five and Chamberlain four.

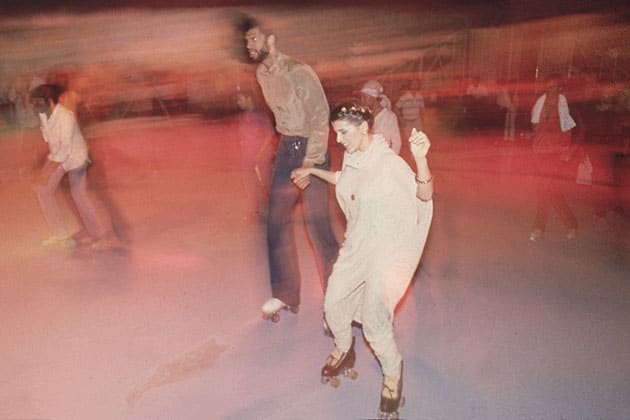

Abdul-Jabbar's athletic competence is not limited to basketball. He is a powerful runner, swimmer, bicycle racer and tennis player. He worked out last summer catching passes at the Minnesota Vikings' training camp with his friend Ahmad Rashad, and he practiced a form of kung fu for several years with the late Bruce Lee. Moreover, he is a terror on wheels at Flipper's Roller Boogie Palace in Hollywood, which he often goes to after Laker games. On a recent night he skated past two girls and heard one squeal to the other, "It's Wilt Chamberlain!"

Thanks in part to his girlfriend, Cheryl Pistono, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was on a roll in 1980.

Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated

Which brings up the perennial question: who ranks first among the great centers -- Chamberlain, Russell or Abdul-Jabbar? Modesty prevents Kareem from saying what he truly believes -- that it is he. "Kareem is a player," says West, his former coach, although he had become angry with Abdul-Jabbar at times when Kareem seemed to be playing less than inspired ball. "A great, great, great basketball player. My goodness, he does more things than anyone who has ever played this game. Wilt was a force. He could totally dominate a game. Take it. Make it his. People have thought that Kareem should be able to do that too. No. That would not make him a player of this game. Russell was a player. The greatest. But he was playing a different game than they're playing now. You can't compare the two of them."

What Russell had, of course--what great players must have in order to win--were other players around him. Abdul-Jabbar has not always had that luxury, and it rankles him that this has never seemed to matter to the press or the fans. "It's the misunderstanding most people have about basketball," he says, "that one man can make a team. One man can be a crucial ingredient on a team, but one man cannot make a team. In the past I have played on only three good teams--in '71 when we won the championship, '74 when we lost to Boston in the finals and '77 here in Los Angeles. It was only when Milwaukee picked up Oscar Robertson and Bob Boozer that we became a good team. When I came to Los Angeles in 1975, the Lakers had to give up three excellent young players to get me. Those guys--Brian Winters. Dave Meyers and Junior Bridgeman--made Milwaukee a good team. I probably had my best year, and the Lakers finished next to last. In '77 we had the best team in the league, but we lost Kermit Washington and Lucius Allen just before the playoffs, and Portland beat us four straight.

"We were playing, more or less, with four guards and me. Don Ford was out-rebounded by Maurice Lucas something like 45-12. Yet everything written said that Walton had outplayed me. Walton played a great series. I played a great series. The Trail Blazers played a great series. The Lakers played a poor one. The press tried to make it seem like I was embarrassed. Walton made one dunk shot on me, and that was supposed to have signaled the end of Abdul-Jabbar being the best."

The press has apparently changed its mind--Abdul-Jabbar is the best again--because so many things have happened to make the Lakers fun once more. "I view that with total cynicism," Abdul-Jabbar says of the press turnaround.

First there was the arrival of the superb rookie point guard, effervescent Magic Johnson. He was going to be everybody's little brother, spark new life into the dour Kareem. Then came a new coach, Jack McKinney, to replace the problematical perfectionist, West. After McKinney suffered a serious injury in a freak bicycling accident 13 games into the season, another new coach, a bright Shakespearean scholar from LaSalle College in Philadelphia, Paul Westhead, took over. Presiding over all was a new owner, millionaire playboy-mathematician Dr. Jerry Buss, who had pumped new life into the town by actually promoting the Lakers, and into the team by rewriting contracts, throwing lavish postgame parties stocked with Playboy Playmates and Bo Derek imitations, and flooding the locker room with the likes of James Caan, Sean Connery and O. J. Simpson.

Said Connery to Kareem after witnessing his first pro basketball game, "Metaphysically as well as literally, you stand head and shoulders above the rest of the gentlemen."

A Hero For The Wired World: Michael Jordan reaches new heights

Every one of the Laker changes has worked like Magic, who has, says Abdul-Jabbar, "incredible talents that he brings to the game. He creates things for us the way nobody ever has for this team." Just as important have been Jim Chones, Mark Landsberger and Spencer Haywood, three strong and talented rebounders who came along this season to remove much of the inside burden from Abdul-Jabbar and enable Forward Jamaal Wilkes to play like an All-Star.

"Early in the season," says Westhead, "everything was Magic this and Magic that. People sort of forgot about Kareem. In a way that was good, because, before long, everybody realized that Magic or no Magic, this team is nothing without Kareem. I mean nothing."

So many good things happening all at once sounds like some kind of Tinsel-town fairy tale. But it so happens that at this moment Abdul-Jabbar is undergoing a rebirth, fighting his way out of the shell he has kept himself in for the past 15 years. It isn't easy. There has been racial hatred and distrust; violence perpetrated against his close friends and violence perpetrated by himself; a bad marriage; and now a messy divorce.

Abdul-Jabbar lives in a 10-room Bel Air house just down the road from Caan and O.J. and near the jazz musician and composer Quincy Jones. It is decorated with several of Abdul-Jabbar's valuable Oriental rugs and pieces of Islamic art he purchased in Africa and the Middle East.

The other day Abdul-Jabbar rather coldly told a visitor he had invited over to wait in the living room until he had finished dinner.

"Kareem!" came a loud, scolding female voice from the kitchen. "Tell him to come in here and sit with you!"

Whispers followed.

"Well, if you're going to be that way, I'll just have my dinner in the living room," she yelled, and came to the door, apologizing.

Cheryl Pistono is funny, friendly, delightfully smart-alecky, wise beyond her 23 years. Like Kareem, she has an uncommon odyssey behind her; somehow it fits that they should have ended up in the same place. She left a working-class family in LaSalle, Ill. at 16 to live with relatives on the Coast, went to Beverly Hills High School and got "into the high life. Hanging out at Hugh Hefner's, weekends in Las Vegas, stuff like that," she says. Like Kareem, she had been a disgruntled Catholic. Only she settled on Buddhism. "Some combination," she says, laughing. "Like oil and water, right?"

Last winter, when she brought Abdul-Jabbar home to meet her family, it was a big occasion. "Everyone was very excited, even though they didn't really know who he was," she says. "The funny thing is that my father is a really big basketball fan who had always loved Kareem, but when Kareem was in his house, he refused to come home. Couldn't handle the racial thing. Now my grandmother, who's in her 80s and lives out here, really gets on him. She cuts the articles about Kareem out of the papers and sends them to him, just to needle him."

Abdul-Jabbar readily acknowledges that Cheryl has had a greater impact on his adult life than any of his teachers, coaches, owners, friends or teammates. She convinced him to seek a divorce from his wife Habiba, whom he married in 1971 but has not lived with since 1973. The divorce is now being settled in court. Cheryl attacks inconsistencies in his religious beliefs--he removes paintings and photographs of human figures from the walls, according to Islamic law, and hides them under her bed when devout Muslim friends visit, for instance--and she rails at him for choosing religious laws over conventional ones. She was horrified that he fathered two children with Habiba after their separation--they have three--and told him so.

"I met a person who had never received anything from anyone but praise," she said. "I mean, he was a god, right? No one ever told him, `Hey, that's--. Why do you do that? That hurt that person.' People have always been afraid to tell him that they don't like him. I never praise him. Never. I'm the only person who ever told him he was full of--."

As if on cue, Abdul-Jabbar bursts from the kitchen, relaxed, beaming. "Cheryl, that was a wonderful dinner you prepared. Really praiseworthy."

"Kareem, you can be such a jerk...."

He laughed loud and hard until Cheryl left the room. Then he grew quiet and serious. He fingered a copy of Heavy Metal, his favorite science-fiction magazine. He was asked about the Alien metaphor. Could it be a metaphor for his life? "I suppose it could," he said. "Like there's an alien inside me trying to get out? Maybe. Maybe the alien is the real me that I have kept locked away for so long, like all my life. I've missed a lot of things, I know. I'm trying very hard to change all that."

In his mind he went back to when he was a boy growing up in the Dyckman Street housing project, a racially mixed community in the Inwood section of Manhattan. Too many bad things had happened over the past 15 years, he says, for him to remember those days with fondness. He was, after all, a different person then--Lew Alcindor, Catholic--and now he finds himself a 33-year-old Muslim. "I feel sometimes that I went right from being a kid to where I am now," he says. Cheryl maintains he is still a kid.

He has no intention of renouncing Islam and becoming Alcindor again. He is a fervent believer, if less zealous than he once was. He just wants to recross the bridges between his past and his present that got burned, and try to recapture what he calls "a sense of reality."

When he was six years old he attached himself to the first and only real hero of his life, Jackie Robinson. "Not because he was the first black baseball player in the majors," Abdul-Jabbar says, "but 'cause he was a hero. See, I understand now what was going on then in terms of what it meant socially. But at the time I didn't understand that. My parents didn't explain it to me. I didn't even know that he was the first black. I didn't even realize that everyone else was white. All I knew was that Jack was out there and it was like Jack against the world and Jack was going to win. Jack took no prisoners. Guys like Sal Maglie would throw at Jack, and Jack would bunt down the first-base line and try to spike the guy as he fielded the ball. Jack was serious. And that competitive intensity that he had--that I understood. But I didn't understand why it was the way it was. I loved Jack."

Because he was what he was, Alcindor soon began to learn all that he could have wanted to know about the two subjects that would dominate most of his life--basketball and racial prejudice. As a boy he could never understand why his white friends seemed to feel that there was something wrong with being black. One afternoon, when he was 12, his best friend, a white boy, and two others followed him home from school, shouting "Nigger! Black Boy! Blackie!" at him. That was when Abdul-Jabbar began constructing the wall.

At the same time, of course, he was becoming the greatest schoolboy basketball player of all time. In the eighth grade, when he was 6' 8", he had his first brush with high-pressure recruiting. Manhattan's Power Memorial Academy and Coach Jack Donohue won out, and Lew Alcindor began attracting a lot more attention than most urban black children received in the middle '60s. In his last three years at Power his teams won 78 of 79 games and three city Catholic championships. But along the way there were more of those moments that reinforced Alcindor's feeling that it was himself against the world, just like Jackie Robinson.

In his junior year Power was playing St. Helena's, an easy opponent, the night before its big game with powerful De-Matha of Hyattsville, Md. As Alcindor recalled in SI (Oct. 27, 1969): "We played rotten and I played rottener than anybody, and at halftime we were only up by six points when we should have had the game settled by then. We went down to the coach's room, and Mr. Donohue started picking us apart one by one and telling us how awful we played, and then he pointed at me and he said, `And you! You go out there and you don't hustle. You don't move. You don't do any of the things you're supposed to do. You're acting just like a nigger!'"

After Power won that game, and the DeMatha game, Donohue tried to laugh off the incident, saying, "See? My strategy worked!" But it worked instead to help shove Lew Alcindor into what he calls his "white-hating period."

"I was 17 years old, being cheered on the basketball court but being called a `nigger' by those same people on the street," he says. That summer riots erupted in Harlem. "I stepped off the subway right into the middle of it. It was chaos, wild, insane, and I just stood there trembling. Cops were swinging nightsticks at everybody, bullets were flying, windows were being smashed, people were stealing and looting. All I could think of was that I wanted to stay alive, so I took off running and I didn't stop till I was at 137th and Broadway, several blocks away. And then I sat huffing and puffing and pondering about what I'd seen, and I knew what it was: rage, black rage. The poor people of Harlem felt that it was better to get hit with a nightstick than to keep on taking the white man's insults forever. Right then and there I knew who I was and who I had to be. I was going to be black rage personified, black power in the flesh."

Despite winning three national titles, life wasn't all smiles for Abdul-Jabbar, then known as Lew Alcindor, at UCLA.

Rich Clarkson/Sports Illustrated

He went to UCLA, influenced in part by a letter from a famous alumnus named Jackie Robinson. Three NCAA championships followed, and UCLA lost just two games in all that time, one being the celebrated Astrodome matchup against Houston and Elvin Hayes. That game took place just eight days after Alcindor suffered his first serious eye injury, a scratched eyeball.

Fame at UCLA did not make life any happier for Alcindor, who had already come to think of basketball as nothing more than business, though it was important for him to be the best. He nearly left UCLA for Michigan after his sophomore year, and after his junior year he incurred a great deal of resentment when he aligned himself with Harry Edwards and called upon all black athletes to boycott the 1968 Olympics. The boycott failed to materialize, although Alcindor himself stayed away, working with black children in New York instead. By his senior year he had retreated into his Islamic studies, had few friends and spent most of his time alone.

"Ever since childhood I had this ability to draw into myself and be perfectly contented," he said in 1969. "I had to. I had always been such a minority of one. Very tall. Black. Catholic. I withdrew into myself to find myself. I made no further attempts to integrate. I was consumed and obsessed by my interest in the black man, in black power, black pride, black courage. That, for me, would suffice."

After his Rookie-of-the-Year season in 1970 with Milwaukee, Alcindor made his conversion to Islam public and changed his name to Kareem (generous) Abdul (servant of Allah) Jabbar (powerful). "I never had any real trouble passing my change off on the public," he says now. "Because of my talent on the basketball court, people tended to avoid engaging me in any conflict if they could help it. The people in Milwaukee were good about it, they realized I wasn't some sort of idiot. The coach, Larry Costello, had some trouble. He kept stumbling--'Lew ... Kareem ... Lew ... Kareem.' He was very self-conscious about not saying the wrong thing."

In 1971 the Bucks won the NBA championship, and Abdul-Jabbar picked up his first MVP award. They won at least 60 games in each of the next two seasons, and lost to Boston in the championship finals in 1974. But life was still dragging on Abdul-Jabbar. His friends had been murdered in 1973, his marriage had broken up, he was shuttered in Milwaukee, a town he was not enthusiastic about in the first place. "I would stay home, read, get into my music," he says. His frustrations built so, that after suffering his second serious eye injury in a 1974 exhibition game, he slammed a basket standard in disgust and fractured his hand.

When his contract expired in 1975 he did all he could to get back to New York, to play for the Knicks, which had been his lifelong dream. When that fell through he chose Los Angeles. He still kept mostly to himself, although there were more people he could be comfortable with--Muslim friends and jazz musicians like Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea. Generally speaking, his teammates at the time did not fit that category. "My feeling about basketball then was that I was paid to play my best and that is what I did," he says, "not to pat guys on the behind and be their friend."

The worst year of his life was 1977. In March his friend Khaalis led the Hanafi Muslim siege on the B'nai B'rith building in Washington and ended up in prison. Abdul-Jabbar became the target of kidnap and death threats. Later in the spring the Lakers, with the best record in the NBA, lost four straight playoff games to Walton and the Portland Trail Blazers. The papers suggested that Abdul-Jabbar was washed up. That fall, on opening night of the 1977-78 season in Milwaukee, of all places, Abdul-Jabbar reacted to an elbow to the solar plexus from rookie Kent Benson by throwing a brutal punch that gave Benson a concussion and broke Abdul-Jabbar's hand. Again, his own violent reaction upset Abdul-Jabbar, but not nearly so much as the reaction from the public and the league office. He was fined $5,000, while Benson was not even reprimanded.

The Ring Leader: Bill Russell helped the Celtics rule their sport like no team ever has

"Everyone's attitude was that it was totally my fault," says Abdul-Jabbar. "So again it was me against the world. I can understand how the punch happened. He was a rookie, he made a mistake. When he did that I thought of all the times I was provoked, abused, bullied, scorned, and I was not going to take one more thing. My reaction was extreme, no two ways about it, but the league's reaction was wrong. It was neither my fault nor Benson's, totally. It was the system's."

Just two months earlier Abdul-Jabbar had first met Cheryl. "I had no interest in him," she recalls, "because I never liked the people who were into the sports mentality, and despite everything else, he obviously was. He expected me to fall all over him. Women always had, but one day he brought me a rose from his garden. He was serious as hell! I thought, oh, I've got to get this person to laugh. All I could think of was to not hurt him."

Abdul-Jabbar insists that basketball was really what his life had been about all along. He loves it and expects to play, he says, "as long as I keep my mental and physical health." But in December of 1977 he was nearly ready to quit. Just a month after his hand had healed sufficiently for him to return to action, he witnessed yet another violent act when teammate Kermit Washington crushed the face of Houston's Rudy Tomjanovich with a punch. "He was miserable," says Cheryl. "I sent him air-express letters saying, 'Kareem, your career is not a jail sentence.' He felt so sorry for himself it was disgusting."

Cheryl "got serious" with him and told him what he had to do. How he had to be more than just a basketball player, he had to be a leader. How he had to stop pushing people away and start listening to what they had to say. How he had to forget about keeping his emotions inside of himself, because they would continue to come out as fits of rage. And they did. Hearing these things from her one evening, he became so enraged he broke two doors in his house off their hinges.

Gradually he has come around, has gotten less "serious." But when a person has been locked in so long, making changes is not easy. Cheryl introduced him to roller skating. It is a staggering sight to see a man his size doing disco moves on wheels with consummate grace. But he does, and he is happy, and he actually blends into the bizarre crowd at Flipper's. Even so, sometimes he closes up. One night a young fan approached Kareem to tell him how great he was. Kareem gave a blank look and the tiniest nod, but would not speak. The fellow skated off in a huff and confronted Cheryl. "Hey," he said, "how can someone be so great on the court and such a--off it?"

Cheryl felt terrible. "Did he nod to you?" she asked. "If he did, it came from his heart, believe me." Then she chastised Kareem.

"It bothers me that people interpret me the way that they do," Abdul-Jabbar says. "I don't mean to be intimidating. I'm about respect. I want people to respect me, that's all. It's something I get from my father. He's a cop--a big, strong man, very quiet. That intimidates people. He was my example. `I'm just like Big Al,' that's what I always thought.

Jabbar helped the Lakers dunk Julius Erving and the 76ers in the 1980 NBA Finals.

Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

"Now I realize what happened to me. O.K., I was big. That never bothered me. I always liked being big. But because I was a basketball star, all my life people had gone to a great amount of trouble to insulate me from things. It was necessary, it seemed then. My high school coach had to insulate me from the flesh peddlers, and there were hundreds of them in New York. At UCLA they had to insulate me from the press. In Milwaukee I signed a very large contract and they were careful not to overburden me. Beautiful. It was all so easy to accept. I liked it that way. And even the people I learned about Islam from felt that it wasn't necessary for me to learn it the way it was generally taught, because that wasn't good enough for me, so they made my environment as pure as possible. My parents were part of it, too. When I was under their guardianship they always told me to go along with the program. I bought it all because there were immediate rewards--winning basketball games. Later I won basketball games and made a lot of money. Looking back on it now, I don't think any of it did me a whole lot of good.

"I didn't realize that I was missing so much. So a lot of the things I'm going through now, the things Cheryl has spoken about, have to do with reviewing my life and picking up on things I did wrong. Now I'm dealing with my life, by myself, for the first time in my life."

Westhead, the rookie interim coach, marvels at the man he had known, by reputation, as "the aloof Kareem." "I expected there to be this so-called `chill factor,' but there is none of that at all," he says. "Maybe it is his soft personality. The guys seem to thrive on it. It's like he's their big brother. He's got so many stories. O.K., maybe a half hour before games, everybody gets quiet and waits for Kareem to tell one of his stories. He tells these special tales about growing up in New York, characters he's met. It's story time, then everybody goes out and plays basketball."

It is true. One day Kareem is telling about how Wilt took him out to dinner when he was a senior in high school: "He had the Bentley and the racehorses and every beautiful woman in Manhattan, and he takes me to his pad and there is the finest woman I have ever seen in my life. I'm 17 and my eyes are big as apples and my jaw is hanging open...." Another day he tells about "the toughest dude who ever lived in Harlem, Sugar Stamp," so named because he used to connive to get sugar-ration stamps during World War II. "One time Sugar hit the number and two guys ambushed him, shot him three times in the stomach. Man, Sugar chased 'em both, beat one to pieces and about caught the other when he finally checked out...."

Once he told about the most amazing player he had seen, a visitor to Harlem from Philadelphia for a playground all-star game. "This dude brought his own cheering section from Philly, man, and I had never even heard of him. Before the game they start screaming, 'Jesus! Black Jesus! Black Jesus!' I thought, who was this dude? He was about 6' 3", and the first play of the game he got a rebound on the defensive end of the court and started spinning! Man, he spun four times! Now, he's 90 feet from the hoop and this dude is spinning! Well, on the fourth spin he throws the ball in a hook motion. It bounced at midcourt and then it just rose, and there was a guy at the other end and running full speed and he caught it in stride and laid it in. A fullcourt bounce pass! After I saw that I could understand all the Black Jesus stuff. I didn't find out the dude's real name until way later. It was Earl Monroe...."

Asphalt Legends: Pickup basketball in New York City

An evening at the Bel Air house with Cheryl and Kareem has grown late. Kareem has talked about a movie he has just made, a spoof on the Airport films, called Airplane, in which, wearing his famous goggles, he plays a co-pilot; a record album he is contemplating making, on which he will play conga drums along with Tito Puente's percussionist, Joe Madera; a shopping trip in Karachi, Pakistan, during which he purchased Oriental rugs and was followed around by 300 people who, because of his great height, regarded him as a rare curiosity; his father--"I escaped a lot of whippin's in my time thanks to Big Al"--and the crowd at Flipper's, where, the night before, ex-football star Jimmy Brown had accidentally crashed into a girl and broken her leg.

Abruptly the conversation dries up. "Kareem!" Cheryl implores. "Tell about Magic."

"Knee Deep," he says. "That's the name of a song Magic keeps playing on his box. He's kind of worn me out with that." He laughs.

"But he had all the stewardesses dancing on the plane after you beat Boston for the second time, Kareem, and he had you dancing too."

"No," he protests. "I wasn't dancing on the plane."

"Pat Riley got off the plane and told me you were in the aisle."

"Nah. Pat Riley wasn't in on it."

"He said you were standing in the aisle and...."

"I couldn't even stand up in the aisle if...."

"I don't believe you!"

"Well, maybe I did do some moves ... in my seat."

He tried to be serious, but he and Cheryl laughed and laughed.

"Kareem, remember opening night in San Diego when you made that hook shot at the buzzer to win the game, and Magic leaped up on you and hugged you and everyone jumped up and down in the middle of the floor?"

"Yeah," said Abdul-Jabbar, laughing. "It was like we just won the seventh game of the championships."

"Maybe you did."