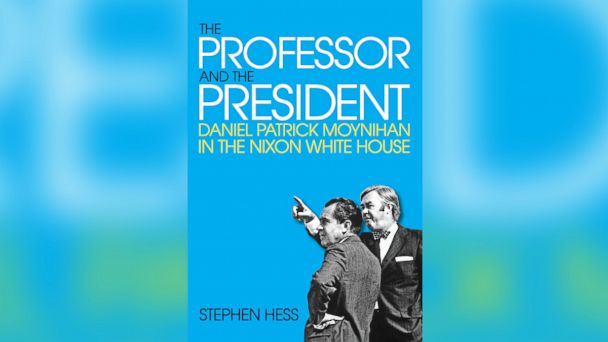

Excerpt: 'The Professor and The President' by Stephen Hess

'The Professor and The President: Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the Nixon White House'

Veteran of four presidential administrations, Stephen Hess, is out with a new book from The Brookings Institution about the unlikely relationship between Richard Nixon and his first assistant on urban affairs, Harvard professor and East Coast liberal Daniel Patrick Moynihan. The story, full of personal, first-hand accounts, is one of chance and lucky timing that brought about a bipartisan friendship at the highest level of Washington.

"It is such a surprising story of how politics really work. What personal relationship really can mean," Hess told ABC News. "These two are almost destined not to get along, and then they found a bond and really liked each other. By the end, Moynihan is what telling the president of the United States which books to read."

Hess said he did not write the book with lessons in mind for Washington today. "It was not written for this moment, but for history," Hess told ABC News. "Still, for this moment, it is awfully nice to remember that there was - and maybe there will be again - a time when people could cross party lines and find agreement."

"It is a very much a story of what went well, and that is nice these days," he continued.

**

Excerpted from THE PROFESSOR AND THE PRESIDENT: DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN IN THE NIXON WHITE HOUSE by Stephen Hess by arrangement with the Brookings Institution Press. Copyright Brookings Institution Press, 2014.

The Memoranda

Nixon has barely finished announcing the Moynihan appointment when Pat's memoranda begin cascading onto his desk. The standard internal "Memorandum for the President," as I remember from my days in the Eisenhower White House, is kept to a page, if possible. The president is a busy man, as are his staffers.

But Pat's memos are long, at times very long, complicated, often convoluted. His style borders on the literary, more like essays, with a tad of the Britishisms he acquired when studying at the London School of Economics, filled with tasty quotations and arcane references. They are often about subjects, such as Negro-Jewish relations, that fascinate Pat and, in his opinion, should fascinate the president as well, even if they are outside presidential powers.

I don't think this is a strategy, at least not at first. It's just Pat being Pat, saying all the things he wants to say to a president if he ever has a chance. Nixon is meeting Pat through the memoranda, his introduction to a man he had not known and yet is elevating to a position of great importance to him and his government.

On January 9, 1969, Pat writes to Nixon:

In the months ahead I will be harassing you with details of the "urban crisis." Whatever the urgency of the matters I bring before you, I will be doing so in an essentially optimistic posture, which is to say that I will routinely assume that our problems are manageable if only we will manage them. This is the only position possible for government. Yet, of course, it does not necessarily reflect reality. It may be that our problems are not manageable, or that we are not capable of summoning the effort required to respond effectively. It seems to me important that you know that there are responsible persons who are very near to just that conclusion. (To be sure, twenty years ago in many scientific/academic circles it was taken as settled that the world would shortly blow itself up, yet we are still here.)

I had thought to summarize the views of the apocalyptic school, ranging in style as it does from the detached competence of Lewis Mumford who for forty years had foretold the approach of "Necropolis," the City of the Dead, all the way to the more hysterical members of the New Left who assume that the only thing that can save this civilization is for it to be destroyed. However, I have just come upon a document of careful men who recently met to discuss the state of New York City. I am associated with a quarterly journal, The Public Interest, which is devoting a special issue to New York. On December 17 we assembled a group of city officials and similarly informed persons for a day-long session at the Century Club. (I could not be present owing to my new assignment.) Paul Weaver, a young assistant professor of government at Harvard, attended as a kind of rapporteur. Later he summarized his impression of the meeting in terms that seem to me persuasive, and as he himself put it, "not a little chilling."

His central point-an immensely disturbing one-is that the social system of American and British democracy that grew up in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was able to be exceedingly permissive with regard to public matters precisely because it could depend on its citizens to be quite disciplined with respect to private ones. He speaks of "private sub-systems of authority," such as the family, church, and local community, and political party, which regulated behavior, instilled motivation, etc., in such a way as to make it unnecessary for the State to intervene in order to protect "the public interest." More and more it would appear these subsystems are breaking down in the immense city of New York. If this should continue, democracy would break down.

Most staff memos to a president are essentially politician-to-politician or expert-to-CEO. But Pat is writing to Nixon intellectual-to-intellectual, without a bit of patronizing. Nixon has never been treated this way before. He loves it!

Now that he is finally to be president, Nixon seems to have room for knowledge other than what he has needed to get there. And for Pat, the professor, there is the delighted discovery that his student is very bright and easy to engage.

January 15, 1969

To: Bob Haldeman

From: RN

The Moynihan memorandum of January 9 on urban problems should be made available to the research team and to the Cabinet members who are on the Urban Affairs Council. It should be emphasized in distributing this memorandum and others like it, which will be coming in, that this is not a final policy paper but the kind of incisive and stimulating analysis which I think should constantly be brought to the attention of policymakers. Be sure also that Garment gets a copy of this memorandum and of others like it in the future.

The president's practice of sharing Pat's memos throughout his government almost guarantees that eventually there will be an embarrassing leak. But that leak-which will outrage the civil rights movement, embarrass the administration, and prompt Pat to offer his resignation-won't happen for another year.