"Burnley," says Tony Booth. "Burnley would be the ideal place to put it. Either there," he adds, "or Bognor." I've asked Tony Blair's father-in-law to outline the changes he would implement were he to be handed absolute power, and he's begun by explaining where he would locate a new, drastically reformed, democratic EU Parliament.

"Reducing immigration would be the first thing," says Booth, an unreconstructed socialist who, on every subject except Europe, is about as far-removed as it is possible to be from the ideology of Ukip. "I don't believe Britain can accommodate 200,000 people every year," he says. "If this carries on we risk civil disruption, and religion will come into it and all that bollocks. This is not about race. If you made the argument economic, I think more people might listen. But we haven't got the balls to tell the EU to piss off."

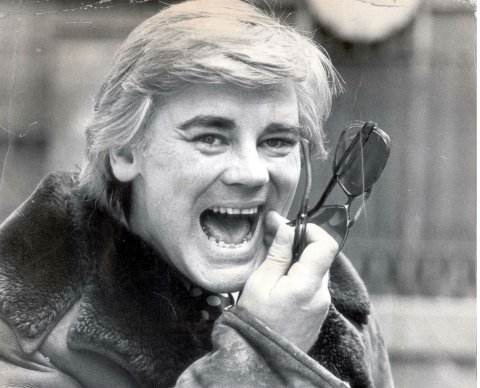

We're sitting in the living room of the attractive terraced cottage that Booth shares with his fourth wife Stephenie, in the picturesque Lancashire moorland town of Todmorden. They have no children together, but he has eight daughters – of whom Cherie Blair is the eldest – from previous relationships. Booth is 83 now and although he has been diagnosed with Alzheimer's and recently spent three weeks in hospital, during which time Cherie came to visit him twice, he retains a lively interest in politics. He is more coherent than most serving MPs I have met.

Booth doesn't enjoy interviews – the most recent one he gave, of any great length, was when we last met, in 2004. He's shed a little weight since then, but remains an enthusiastic smoker and has not lost his fondness for mischief. "The truth is that if you put me in charge of the country tomorrow," he says, "my first instinct would be to go to the Treasury, empty it, then do a runner."

I'd assumed that his first decree would have involved the renationalisation of everything. "The problem now," he says, "is that the situation is irretrievable. I still believe that capitalism is a clever institution imposed by the rich on the poor. Control has passed into the hands of bankers and bureaucrats. We are relying on the guys who have been fiddling us since the days of Adam and Eve."

There is a temptation, Booth says, "simply to pass the ball. Hand it to the Tories and say, OK. There you go. You did this. You sort it out. Because capitalism, sooner or later, is going to be unable to pay the bill. And then they'll have to renationalise industries whether they want to or not."

Is there any leader who could revive the Labour Party? How about Tony Blair, in the highly unlikely event that he could be persuaded to run again? "Funnily enough, I think he might have an outside chance. Because people would say: well, at least he is the devil we know.

And with Miliband, you find yourself thinking, this is a good kid, but when is he going to get into long pants? Are we just putting him up as a dummy until we find the right person?"

Booth's response to the question of whether the current Labour leader could win an election is characteristically unambiguous: "In your fucking dreams. This is not play school."

There is a peculiar conformity about the three party leaders, I suggest to Booth. They all look like prefects waiting to nick you for smoking. "Yes. I hope that, lurking somewhere in the Labour ranks, is a female politician who will emerge and speak the truth. The one thing the Tories really don't like is a nanny. Nannies frighten them. We need somebody in the mould of [Harold Wilson's formidable ministerial colleague] Barbara Castle."

Just as every witch has her familiar, so every long-serving head of government seems to acquire a family member who struggles to achieve the decorum expected of those associated with high office.

You may recall some of the scenes precipitated by Bill Clinton's brother Roger (including cocaine use, and an assault involving a female friend, a heavy frying pan, and a second woman whom Roger had paid $150 "to cook rice".) Not to mention Mark Thatcher, whose appetite for wealth exceeded his talent for its orthodox procurement, or Jimmy Carter, whose brother Bill's life was dominated by two sincere but politically unhelpful passions: export lager and Muammar Gaddafi.

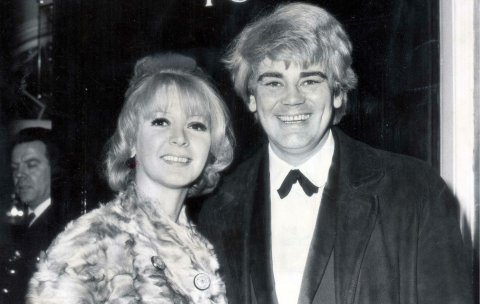

But no pair on that list was divided by a world view that deviated quite so spectacularly as Tony Blair's has from his father-in-law's. Blair has been one of the very few modern statesmen who appears to have kept his libido under control. Booth, on the other hand, bared all in Kenneth Tynan's notorious show, Oh! Calcutta!, and played Sid Noggett in an uncomplicatedly erotic series of films that included Confessions of a Window Cleaner. It's probably fair to say that the role of Noggett – a priapic Liverpudlian with a van – required less of a mental leap for Booth than some other characters he has inhabited, such as Hamlet. While Blair is the embodiment of placid monogamy, Booth – in addition to his four wives – has had two long-term partners and innumerable brief liaisons.

Booth, while best known to red-top readers for his intimate life, is a highly intelligent man who, you feel, could have excelled in any field. He was instrumental in propelling Tony Blair towards Westminster. Booth recalls arranging a lunch for his son-in-law, at Soho's Gay Hussar restaurant, with Labour MP Tom Pendry, during which the future prime minister was persuaded to stand for office. At that time Booth, nationally famous for playing Mike Rawlins, the "Scouse git" opposite Warren Mitchell in Johnny Speight's Till Death Us Do Part, and as the husband of Coronation Street star Pat Phoenix, was well placed to generate publicity both within and beyond the Labour party. It seems curious that many forget the vital role he played in shaping Blair's career.

"We did what we could," he says. What would have happened otherwise? "I think he would have become a barrister."

Ron Rose, the playwright and former Labour councillor for Doncaster, told me that, "The crucial thing you must understand about Tony Booth's relationship with Blair is the part that he played in getting him elected. When I began canvassing, he was already telling people about his son-in-law, who was going to be prime minister. This was in the early '80s, before Blair was even on the political radar. Tony Booth is the best canvasser I have ever seen. He was driving all over the country, working for the day when Tony Blair would become leader, long before anybody gave the idea credence." Booth concedes that, "I helped get him into [his parliamentary seat of] Sedgefield."

Booth and Pat Phoenix had also campaigned for his daughter Cherie, in her unsuccessful 1983 candidature at the Tory stronghold of North Thanet. "On reflection," he tells me, "I wonder if it should have been Cherie. She wouldn't have taken any shit from anybody."

DRINKING WITH TONY

Tony Booth was born in Waterloo, Liverpool, the son of a merchant seaman. He left school at 14 after his father was killed in an accident. Even then his ambition was plain. "I thought actors were rogues," he says. "That's the company I wanted to keep." His first wife Gale, mother of Cherie and Lyndsey, stayed in Liverpool while Tony went to London and worked in repertory. He caught the eye of Johnny Speight, writer of Till Death Us Do Part, while he was heckling the then shadow home affairs spokesman George Brown, during a Labour election rally in 1964. Speight moulded the role of Mike Rawlins to suit Booth, who lounged on the couch reading the socialist newspaper The Militant while Warren Mitchell berated the Irish, Asians, blacks, Arabs and Jews in a show whose satirical intent eluded many viewers.

One area where Booth differed from his character was in his relationship with drink. Mike liked the pub but he was not an alcoholic. Booth began drinking heavily after the end of a relationship with Boston-born Julie Allan – then a TV scriptwriter, subsequently a Hollywood producer – that had caused him to abandon Gale in 1961. Cherie was seven, Lyndsey five.

Booth and Allan had two daughters, Jenia and Bronwen. The couple had spent five years together before Allan left London abruptly for the States, taking the children. "I never really had the capacity for alcohol," says Booth, whose mother's maiden name was Tankard, adding that he was "a total asshole when I drank".

Few dispute that assertion. "I have never seen a man who could start a fight so quickly," says his friend and fellow actor Mark Eden. Once, Eden recalls, "I was having a drink with him in this quiet pub. I went to the loo, leaving behind this civilised, tranquil scene. I couldn't have been gone two minutes. I came back to witness this horrible melee, with Booth at its epicentre. The landlord was trying to grab him; Tony was punching somebody. Strangers were trying to knock him out with pint glasses. He achieved all this in the time it took me to go to the gents."

At a party thrown by Harold Wilson, Booth famously hailed the prime minister of Luxembourg, mistaking him for a wine waiter, and ordered Veuve Clicquot. "I'll say this for the guy," he recalls. "He came back with two full glasses." And now? "Now," Booth says, "I hate the taste of alcohol."

The mayhem reached its height in the mid-1960s, when he was with the third of his significant partners, Pamela Smith, usually known by her modelling name, Susie Riley. Susie, the mother of his daughters Emma and journalist Lauren, has alleged that he beat her. Their only physical confrontation, Booth has repeatedly insisted, occurred after Susie had "stuck a knife in my hip, and was trying to pull it out to stab me again. What was I expected to do?"

He gave up drink 36 years ago, almost to the day, after an incident in which he locked himself out of the London flat he shared with Susie. Booth had bonded with a group of SAS men, who had come home with him. While he was attempting to climb into the first floor loft, using three drums of paraffin as a ladder, the soldiers set fire to a door immediately below him, explaining that this was "what we do to the Paddies".

"I was halfway into the loft," Booth told me when he described the episode in detail the last time we met. "I heard this whooooomph. I screamed at my family to get out. I let go and dropped back outside. I thought the soldiers would have moved the paraffin drums. I was wrong."

In the explosion that followed, the heat was so intense that his testicles retracted into his body. Booth was pronounced clinically dead three times. He spent six months in hospital and had 26 operations. There are severe scars on his hands and torso. In the wake of the accident he looked up an old flame, Coronation Street legend Pat Phoenix, who took him in to her Cheshire cottage in the autumn of 1980, and nursed him to health. In 1986, Phoenix became his second wife, days before she died of lung cancer. Two years later he was married again, to Nancy Jaeger, 23 years his junior. Jaeger is the mother of his youngest child, Joanna, who will be 25 on Christmas Day.

When Joanna was seven, Booth introduced her to Tony Blair. He persuaded her to ask, "What will you do for pensioners like my daddy?" Blair replied: "For your father – euthanasia. For everyone else, we'll do the best we can." He has been married to Stephenie Buckley for 18 years. "The press usually ignore me," she says, "because I won't talk to them. So they go back to women he hasn't seen for 20 years."

There was a lengthy feature in one popular newspaper about his 80th birthday party, hosted by the Blairs at their Buckinghamshire mansion, that focussed on people who were absent, principally estranged family members. "The press," Booth remarks, with just a trace of sarcasm, "have been bloody marvellous."

THINGS CAN ONLY GET BETTER

There's no doubt that, in the initial momentum that he gave to Tony Blair, Booth helped give life to a political creature whose trajectory would deviate significantly from the one his father-in-law had anticipated.

When we last met, I reminded Booth of some lines from his memoir, What's Left, where he wrote about "the beautiful thing that happened on May 1 1997", and described himself standing in Blair's bathroom, on that night of the landslide victory, whistling Things Can Only Get Better. He still has his son-in-law's hastily-discarded shirt, which he picked up from the floor that night, as a souvenir. In retrospect, do you feel . . . "That a spectacular opportunity was missed? Yes. However, I must say, of every prime minister, that the moment they walk into Downing Street, they lose touch with reality."

You opposed the second Iraq war, I remind Booth. You marched against it. You used to talk about Blair's vision. When you look at the scenes from the Middle East now, don't they look less like a vision, more like a nightmare?

"Yes."

The unfortunate truth being that, whatever good things Tony Blair might argue that he achieved, Iraq is the thing he'll be remembered for.

"Yes. But what can you do?"

So, indirectly, we can hold you responsible for the second Iraq conflict?

"Yes. That was me. Single-handed."

Did you try to change his mind over Iraq? Booth laughs. "At that point, you couldn't get anywhere near him. Well, that's not true actually. But he is not going to tell me that someone is holding a gun to the country's head. I imagine that diplomats give instructions and say, this is what you have to do, or we will destroy you."

Are you suggesting that full power does not reside at Number 10?

"Of course it doesn't. It resides in capitalism and the Bilderberg group. There is not a politician in the world who has real control."

Was there ever a point when your political differences threatened your personal relationship?

"No. I didn't always agree with him and there were times when we had rows, but he was his own man . . . and you know my daughter had a hell of a lot to do with what went on. I did tell him that he had to get rid of that Gordon Brown."

Why?

"Because," Booth replies, "Gordon Brown is a pain in the ass. He is a pain in the ass. I once said to Tony, 'Come down and look at this door. You read it.' And he read out the title 'First Lord of the Treasury.' I said, 'And who might that be?' He said, 'Me, of course.' And I told him, you tell that . . . word we are not supposed to use . . . what to do. He doesn't tell you what to do.' Brown is a really nasty piece of work." I explain that I had a conversation with a senior associate of Tony Blair's some years ago, during which I suggested that, whatever else Blair had done, he was driven by a moral purpose. The reply was: "No. You're wrong. It's money that he loves."

"I would require notice," Booth says, "before commenting on that remark."

He does appear to have made an awful lot of money.

"Not when he was in power."

No, since then.

"Well, he does have a huge number of staff . . ." Booth goes on to address the pressures placed on a politician at the highest level.

"I remember once travelling in a car with him. The guy sat with us looked incredibly miserable. When I asked why, someone said, 'It's very simple. He knows that, in the event of real trouble, his job is to take the bullet.'"

How do you define yourself now?

"I am a busted flush," says Booth, good-naturedly. "A socialist busted flush. Johnny Speight used to say to me, 'You are one of these idealists. Idealism won't get you anywhere.'"

The world is at war, Booth's character informed Alf Garnett in one episode of Till Death Us Do Part. Pensioners are struggling, abandoned by the policies of your moribund government. Was Speight right? "I don't believe so. I'm still an idealist. I can't help it. I know the difference between right and wrong. And I will not quit the field."

END GAME

We adjourn to Gusto, his local café, where the staff offer him gammon and eggs. Booth, still delicate from his period in hospital, chooses chicken broth. "The NHS," he says, "saved my life. When I was wheeled in, they said, 'Oh look: it's Tony.'"

Because they recognised you from television?

"No," says Booth. "From demonstrations." He is not a man to shirk a subject, least of all his own mortality. There is something of a disagreement going on, he tells me, concerning his funeral arrangements. "Cherie," Booth says, "wants a requiem mass. I have asked to go down the aisle to Jerry Lee Lewis's "Great Balls of Fire". Requiem mass? Bloody hell. If they do that, I'm not coming."

The energy that he once dedicated to the stage, then to the cause of pensioners, is now reserved for the Alzheimer's Society. Positively diagnosed though he may be, as we stand outside the café, Booth proves that he has lost none of his memory for text: he recites a passage from Bernard Shaw's The Devil's Disciple, and remembers a line by the playwright Stanley Houghton that used to be displayed in the bar at Manchester's Library Theatre.

Elderly as he is, I think the motto sums up Tony Booth's vigour and optimism rather well. "The younger generation is bound to win," Houghton wrote. "That's how the world goes on."

Booth sees his work for the Alzheimer's Society as "a natural progression. I knew Dylan Thomas. And I love those lines of his: 'Do not go gentle into that good night . . . Rage, rage against the dying of the light.'

"What a wonderful poem. When I first heard it I wanted to cry. That was many years ago, when it reminded me of my father. Now I'm in that position. And I do rage, trust me. I rage all right. It's not a proper day," Booth adds, "without a good rage."