Living and working in Britain for nearly two decades has taught me what it's like to be on the receiving end of racism. Entering the job market as a postgraduate I was told, on numerous occasions, to change my name to fit in. Comments thrown at me from strangers range from "do you sell DVDs?" to "do you come from a big family?" But verbal insults are nothing compared with being searched by the police on the street for an hour because they chose to believe the claim by a white man who'd assaulted me that I was mugging him.

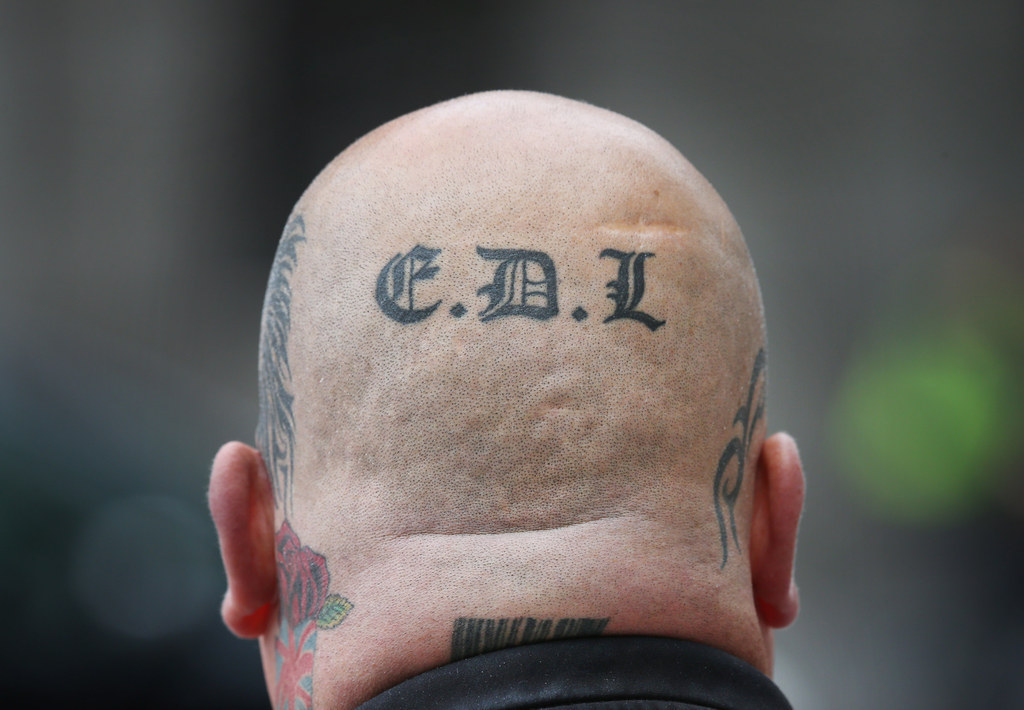

I first encountered Britain's far-right politics while leafleting with local anti-racist campaigners on Dagenham's council estates during the early 2000s, a period when the BNP gained electoral support. I had people telling me on their doorsteps that "immigrants should go back to where they come from". The BNP has faded, but racist politics thrives. Since 2009, I've witnessed the growth of a far-right street movement centred around the English Defence League (EDL). I wanted to understand it.

In my forthcoming book, We the Outsiders: Coming Face-to-Face With the British Far Right, I examine the human reality behind the angry, hateful faces of far-right street mobs that appear on our TV screens. Who are these men and women who become drawn into the politics of despair?

My quest for understanding began in Luton, the home of the EDL. On the rundown Farley Hill estate, where many EDL followers come from, someone referred me to Darren, a builder and a born-and-bred Lutonian. I was told that Darren, having been drawn into the movement in 2009, had played an active part in the wave of demonstrations that led to the EDL's founding. He was also closely associated with its leadership. He asked BuzzFeed not to print his surname, fearing his kids might be targeted for abuse.

Before I met Darren, I had in my mind the picture of a thuggish-looking white male, possibly a skinhead with tattoos. He would be anti-immigrant. He would spout racist views but be unable to articulate the reasons behind them. These preconceptions made me nervous when Darren walked towards me that evening, still in his work clothes with white paint on them. He shook my hand and said apologetically, "I haven't had time to get changed yet." His politeness disarmed me. Then he welcomed me to his home, a terraced house in a quiet neighbourhood, and introduced me to his family.

When we finally sat down to talk at his dining table, Darren's first words surprised me. He had just ordered my first book, Chinese Whispers, and had read the first 100 pages. "Honestly, I didn't realise," he said. "I didn't look at it from that point of view before. Now I think we've all been shafted… How come our wages have dropped this much? Lads coming over from other countries aren't getting nothing, either. If they can't get what they want and we are not happy with it, whose interests is it suiting?" He then used the word "the undocumented" to refer to the migrant workers I wrote about. Wasn't this man an EDL activist? I was puzzled.

Over the following year, Darren and I met and talked regularly. What follows are the edited highlights of our many encounters.

When was the first time you came across racism? How has it affected you?

Darren: Through the late 1970s, you had the National Front (NF) and British Movement who were jumping on our football. I was at school when NF affected my life for the first time. Black lads started fighting with the white lads. It had all been easy up until that point. We all went to football and enjoyed the game. It was always black and white together. Then when NF made big inroads on the terraces and infiltrated all the communities with leaflets, whether you liked it or not, you had to be involved. You had to choose your ideology. You had to work out which side you were on. The black mates felt very threatened. At first, I remember saying to them, what is all this about? They said, "You don't know because you're not black." If you sat on the fence and watched your black mates getting abused, that wouldn't be acceptable. So you find out who you are, without ever thinking you had to do that.

What were the biggest changes that happened to your town in the past two decades?

D: Drugs have become a huge problem. Opposite the Parrot pub (on the Farley Hill estate), you have some lovely little council flats. The council just put crackies in there. It was never like that. Heroin was creeping in. If you're not working, you're gonna be taking or selling drugs. The local government stopped investing in the estates. There's no more affordable social housing. The estates were turned into slums. The government doesn't care about young people. Gordon Brown talked about apprenticeship; my son is 24 and is one of the few lucky ones who got apprenticeships. There's none for his generation. All my son's mates are out of work, desperate to get an apprenticeship. They want progression. They want to do something. They want to be called something.

What was the background to your involvement with the EDL?

D: The mood in Luton changed in 1991 and I knew something big was growing. I put it down to the Gulf War invasion. Back then, we didn't care about politics of the world. The world never comes to Luton. Back in the 1980s it was all about football and the gang – and then all of a sudden, politics came in the 1990s. There was a sense of feeling among the Muslim lads that it was all the West's fault. It was a war for oil. Hostility grew between white lads and the Muslim lads, and it was no longer just a lads' thing. The conflicts escalated, with street fights and beatings. Then in 2009 when Muslims were protesting against the returning soldiers, it was the straw that broke the camel's back. It was like they weren't Lutonians.

How did it feel like to be seen as a racist?

D: To this day, I can't shake off the shame I felt on a Birmingham demo when two white middle-aged women walked past me and spat on my face, shouting at me, "Nazi scum, get out and run!" I guessed they were from the contingent of people from Unite Against Fascism, an organisation I came across for the first time that day. I could cry. I felt instant shame. To be spat on by two white-haired, middle-aged women was like my mum spitting in my face. At that moment I just wanted to fall between the cracks in the pavement … but I was there and I couldn't just disappear. I couldn't speak. I felt my whole life just been turned upside down.

What were the key factors that led to your decision to leave the EDL?

D: The neo-Nazis were always there. My West Indian mates didn't feel safe; the presence of Nazis frightened them. On the demos, Luton lads stuck with Luton; because then you know you're safe. And if anyone comes to you for your black mates, you know what to do. At demos, we had the football mentality where we all stuck together. No one's touching my mates. Just like being on the terraces. On one of the Birmingham demos, an NF skinhead from Sunderland was there ... and happened to be trapped amongst my West Indian mates because police were blocking the roads. He seig-heiled in front of my mates. I started considering cutting all ties with the EDL because I knew it was the wrong path. Then the neo-Nazis got organised and turned up in bigger numbers. Demos were filled with punch-ups. They came with screwdrivers.

Defending the English way of life – that's an illusion, isn't it?

D: It was fear that drove people there. Many family men, they want to know what the future holds for their families. Then you've got other lads who are simply crying for help. … A lot of them can't articulate how they feel, so they let someone else speak for them. These lads have never had a job. Never visited a dentist in the last 20 years. Around 30% of the EDL was made up of unemployed lads. I could see them going out looking for hope. And what is presented to them is just like that video "This Is My England" on the EDL website: It's a mirage. The beautiful landscape and the pretty things they see of rural England on that video, about their country, their nation, are not within their reach. … It's not theirs. But they followed it. They acted out their feelings. They follow their instinct looking for some meaning. But they'd been defeated years ago. Just defeated.

I'm not sure you've ever been interviewed by a non-white person. What were your expectations before we met the first time?

D: To be honest, I had few expectations except that you're an author and probably are of a higher intellectual level than myself and I should find out about you before our meeting. I was hoping that your intelligence would be pragmatic as well, and you'd understand the situation I'm in. I also hoped that I could pronounce your name properly.

Has our communication over the year affected or changed you in any way?

D: Massively. It's been a real game-changer for me. It's made me analyse myself, on a much deeper level than I'd ever done. It made me think a lot about my past. After every "consultation" we had, I'd gone away and thought about what I'd said and how that could appear to others. Sometimes after our meeting, I felt bad, because our talk made me confront what's deep in me. I asked myself, who was I? Was I just an animal on the street? Who am I? You came to my home and I was always able to talk freely without being told off or shouted at. You didn't just come to get a story and leave. It has made me trust – I've never trusted to this degree because I didn't want my feelings to be hurt. But this time, for the first time in my life, I gave everything out. You heard what's deep in my heart, the truth.

In the summer of 2014, six years after joining the the EDL, you joined Labour. You also joined UCATT, the union for construction workers. How did you reach that decision? Do you see that as a fundamental break from the past?

D: I've come full circle. I see it as going back to my working-class roots. I think I've always been a socialist deep down, without knowing. I look back at the 1980s as if it were a black-and-white era, without any colour. The struggle remained fresh in my memory – it was a real hardcore decade for the working class, following on from the winter of discontent. ... In the past, individual working-class people were never afraid to stand up and have a say. We'd had that since the 1970s and all the way to the 1980s. … There was very much a community spirit back then. We had the Toxteth riot of 1981. … We had the miners having a say. … But it's been different since. The community spirit was all smashed during the Thatcher years. … I regretted having joined the EDL. It ain't nowhere to go. I want to be part of making a difference. For me, putting the EDL street movement behind and joining the union and labour movement was one of the most important decisions in my life.

You've said that you are now always prepared to take part in challenging racism and to speak out against the far right. You've met with several union organisers to express your interest in doing seminars on fighting racism in Britain. What are you planning to do next?

D: Locally, I'm talking with someone from Islamic Cultural Centre and we have a lot in common. I took him to his first Luton (football) game. I took my younger son with us and we all had a good day. I'd like to work with him to promote football in all communities and get people from all backgrounds to come and support Luton team. It's one way to bring communities together. With my own union, UCATT, which I recently joined, I'm working out what I can do. I'm certainly prepared to make a stand with workplace issues and talk with colleagues about them. I used to feel that no one was there for us. Now I feel different. I feel engaged. I wish I'd known what I know seven years ago – I could have channelled things through the union. I know I could have.

Darren's openness during the past year has enabled me to see the material circumstances that drive some amongst the working class to the politics of despair. It has also opened my eyes to the possibility of change: that people can shake off a toxic ideology, over time, simply by applying a little logic and humanity. Darren's story makes me see that working classes across ethnic lines have much more in common than we know. He tells me the experience of meeting me has changed him. I think it has changed me, too.