‘Culture is a human right’

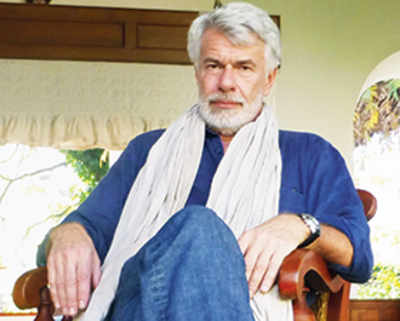

Chris Dercon, director of London’s Tate Modern, on why governments need to take public art initiatives more seriously.

Despite a massive fund crunch and an unexpected thunderstorm, the second edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale opened in full strength on Friday evening, thanks to support from the world art community at large, both, monetarily and in spirit. And one of its most passionate adherents, Chris Dercon, director of the Tate Modern in London, is enthused to be present while it’s still in the process of coming together.

“Even two years ago, when I visited Kochi, people were saying, ‘Oh, the Biennale is not ready’,” he shares, when we meet on Saturday morning. “But it shouldn’t be. It’s about the making.”

“What makes me most angry is that the government here is constantly talking about preserving heritage and tourism without giving it much support or credit,” he says. “This Biennale, for instance, is contributing to tourism and economy, not only in Kerala, but also across India. One can’t be short-sighted.”

“Culture is a human right,” he says, emphatically. “It’s what defines a nation. And the government needs to recognise that. They should stand for it and support it.”

Out here, Dercon seems particularly impressed by the “fantastic” installation created in clay, polyurethane, hay and found objects, by 26-year-old Mumbai artist Sahej Rahal, and considers artist Prajakta Potnis his “big discovery”. “Her work is one of the most important at this Biennale,” he believes.

Yet, the three-month-long event is just one of the many Indian preoccupations Dercon indulges in. “My interest in Indian arts and crafts was ignited while working at the museum in Rotterdam because they had an important modern, contemporary and traditional design section,” he shares.

“Besides, I am Belgian, so I am naturally interested in textiles and fashion.”

His interest first drew him to the textile collection of Praful Shah (of Garden Silk Mills), who later produced a piece for Richard Tuttle’s installation for the Turbine Hall at the Tate.

Over the years, Dercon’s interest in India has grown. “From the work I see at the museums to the Mumbai galleries as well as alternative spaces such as Clark House Initiative, my interest in Indian art is varied and many,” he says. “I am also one Alibagh’s biggest fans. It is home to the museum of Dashrath Patel’s work run by Pinakin Patel and where famous artist Nasreen Mohamedi was buried. For me, it’s a very special place.”

Then there is the connection with artist and Indophile, Howard Hodgkin, who, along with art historian and critic Geeta Kapur, curated the first Indian show at the Tate, back in the ’80s and his friendship with ace architect and urban planner Charles Correa. Flipping through the pages of the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2014 guidebook, Dercon draws our attention to Valsan Koorma Kolleri’s work, How Goes the Enemy, created in laterite, mud and baked earth. “It reminds me of what Charles told me about Indian garden architecture,” he says. “This, however, is a work in progress, but very exciting to me.”

Another work in progress that’s close to his heart is the retrospective of Bhupen Khakhar’s work, that he is curating. It’s set to open in June 2016.

Khakhar, according to him, dealt with two significant issues - class and sexuality - that weren’t openly discussed in the 1970s and 80s. “The way he dealt with sexuality, in an open and didactic way, is almost pedagogical,” Dercon explains. “He tackled the subjects in a way that deviated from the international scene, combining miniature-style with the painting of tomorrow.”

The late Baroda-artist’s work resonates with the language of the Tate, he says. So does work by artists Sheela Gowda, Sheba Chhachhi, Anita Dube, Zarina Hashmi, Bani Abidi and Naeem Mohaiemen, all acquired by the South Asian Acquisitions Committee, chaired by Delhibased collector Lekha Poddar.

“We buy these works not because we want to build a South Asian wing, but because they speak to works from other countries that are housed in the museum. We want different regions to have a dialogue with one another through art,” he says. “Come to think of it, this Biennale is built on that idea, too.”

Despite a massive fund crunch and an unexpected thunderstorm, the second edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale opened in full strength on Friday evening, thanks to support from the world art community at large, both, monetarily and in spirit. And one of its most passionate adherents, Chris Dercon, director of the Tate Modern in London, is enthused to be present while it’s still in the process of coming together.

“Even two years ago, when I visited Kochi, people were saying, ‘Oh, the Biennale is not ready’,” he shares, when we meet on Saturday morning. “But it shouldn’t be. It’s about the making.”

The lack of public support for the arts in India riles 55-year-old Dercon, who has held top jobs at MoMA PS1 in Queens, the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, before spending eight years at Haus der Kunst, followed by his current stint at Tate.

“What makes me most angry is that the government here is constantly talking about preserving heritage and tourism without giving it much support or credit,” he says. “This Biennale, for instance, is contributing to tourism and economy, not only in Kerala, but also across India. One can’t be short-sighted.”

“Culture is a human right,” he says, emphatically. “It’s what defines a nation. And the government needs to recognise that. They should stand for it and support it.”

Out here, Dercon seems particularly impressed by the “fantastic” installation created in clay, polyurethane, hay and found objects, by 26-year-old Mumbai artist Sahej Rahal, and considers artist Prajakta Potnis his “big discovery”. “Her work is one of the most important at this Biennale,” he believes.

Yet, the three-month-long event is just one of the many Indian preoccupations Dercon indulges in. “My interest in Indian arts and crafts was ignited while working at the museum in Rotterdam because they had an important modern, contemporary and traditional design section,” he shares.

“Besides, I am Belgian, so I am naturally interested in textiles and fashion.”

His interest first drew him to the textile collection of Praful Shah (of Garden Silk Mills), who later produced a piece for Richard Tuttle’s installation for the Turbine Hall at the Tate.

Over the years, Dercon’s interest in India has grown. “From the work I see at the museums to the Mumbai galleries as well as alternative spaces such as Clark House Initiative, my interest in Indian art is varied and many,” he says. “I am also one Alibagh’s biggest fans. It is home to the museum of Dashrath Patel’s work run by Pinakin Patel and where famous artist Nasreen Mohamedi was buried. For me, it’s a very special place.”

Then there is the connection with artist and Indophile, Howard Hodgkin, who, along with art historian and critic Geeta Kapur, curated the first Indian show at the Tate, back in the ’80s and his friendship with ace architect and urban planner Charles Correa. Flipping through the pages of the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2014 guidebook, Dercon draws our attention to Valsan Koorma Kolleri’s work, How Goes the Enemy, created in laterite, mud and baked earth. “It reminds me of what Charles told me about Indian garden architecture,” he says. “This, however, is a work in progress, but very exciting to me.”

Another work in progress that’s close to his heart is the retrospective of Bhupen Khakhar’s work, that he is curating. It’s set to open in June 2016.

Khakhar, according to him, dealt with two significant issues - class and sexuality - that weren’t openly discussed in the 1970s and 80s. “The way he dealt with sexuality, in an open and didactic way, is almost pedagogical,” Dercon explains. “He tackled the subjects in a way that deviated from the international scene, combining miniature-style with the painting of tomorrow.”

The late Baroda-artist’s work resonates with the language of the Tate, he says. So does work by artists Sheela Gowda, Sheba Chhachhi, Anita Dube, Zarina Hashmi, Bani Abidi and Naeem Mohaiemen, all acquired by the South Asian Acquisitions Committee, chaired by Delhibased collector Lekha Poddar.

“We buy these works not because we want to build a South Asian wing, but because they speak to works from other countries that are housed in the museum. We want different regions to have a dialogue with one another through art,” he says. “Come to think of it, this Biennale is built on that idea, too.”

GALLERIES View more photos