He scowls at us from under a rain cape, water dripping off the peak of his army cap. He flourishes my passport. "Britain," he says. "You are from Britain."

We are standing at a rebel roadblock on the main Zaporozhiye to Donetsk highway which does not appear to be under any kind of adult supervision.

The skinny soldier with my documents stands alone under a lashing September rainstorm. His even younger comrades huddle under a nearby tarpaulin draped over a pile of sandbags. He is a scrawny farm boy, no more than 20, with the kind of open face that should have a smile on it. Instead, his mouth is soured into an ugly pout.

"Tell your Daniel Radcliffe," says the young rebel, leaning into the car with weary, murderous languor. "Tell him that I used to love Harry Potter. But then I read that he was a drug addict. Tell him I'm very disappointed."

"I'm sorry to hear that. But I don't think its true."

The kid snorts, cocks his head in a gesture of contempt, and hands me back my passport and press accreditation. "But I read it," he says, putting a definitive end to the discussion.

I scroll through a variety of possible responses to this. "No. Really. Its wrong, what you read. Daniel Radcliffe is not a drug addict."

The kid nods resignedly as if he'd love to believe me, but knows better. He waves my driver and me on to continue our journey to Donetsk and turns back to the sagging tent of camouflage netting by the roadside.

Poor kid.

He used to love his Harry Potter. But now he's grown up, and the world has disappointed him.

This time last year he lived in a different country – a country called Ukraine which was at peace, if not exactly in harmony with itself.

Then on 21st November 2013, a small group of protesters gathered on Kiev's Independence Square to protest that their President, Viktor Yanukovych, was refusing to sign a cooperation deal offered by the European Union. They called their movement "Euro-Maidan," after the Ukrainian name for the square. No one took much notice.

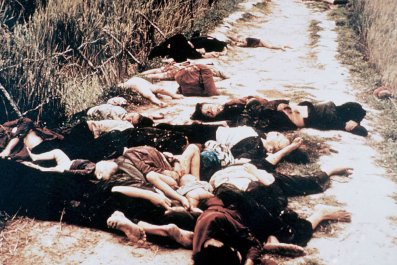

Just six months later, Russia and Ukraine were effectively at war. Yanukovych and his mistress had fled the country. Russian forces had annexed Crimea, the first such land-grab in Europe since World War Two. Chunks of Eastern Ukraine's Donetsk and Lugansk provinces had declared themselves "People's Republics," independent of Kiev's rule – supported by Russian regular troops, armor, and surface-to-air missiles. Central Kiev had been turned into a war zone after running battles between hundreds of thousands of protesters and police.

Malaysian Airlines flight MH-17 had been blown out of the sky by a missile fired by rebels, killing 298 people. In all, over 4,000 people have been killed in Europe's newest civil war.

As a result of all this, two important things happened. First, Ukraine became a country in a meaningful way. In the 23 years since it became independent from the USSR, Ukraine could not decide whether it was going to become a law-abiding, European nation of shopkeepers like its Western neighbor (and some-time ruler), Poland – or take its place alongside Belarus and Kazakhstan in a revived Russian Empire of kleptocratic dictatorships.

Vladimir Putin settled that question once and for all. Without the Russian-speaking population of Crimea, Donetsk and Lugansk, there will never again be a pro-Moscow government in Kiev. At the end of October strongly pro-European parties swept to power in the Rada, Ukraine's parliament. At the same time the European Union and Nato found – for the time being at least – the mettle to agree on sanctions in Russia and economic and logistical support for Ukraine.

The war for the East continues. The economy teeters. The ultra-nationalists may not have done well in recent elections but they are armed and organized into self-governing "patriotic battalions" fighting independently of the government's command. A recipe for disaster of Yugoslav proportions, perhaps. And yet most Ukrainians remain surprisingly hopeful. "We found out who we are. And who are aren't," says Ruslana Khazipova, a young singer with the band Dakh Daughters. "We are free. And we aren't Russia's bitch any more."

The second thing that happened – the more serious thing, the thing that could yet hatch global disaster – is that Russia has been changed by the Ukraine crisis. Russia has turned sharply, and in the space of a few short months, into an older, more vicious version of herself.

DONETSK REVISITED

Harry Potter far behind us, we drive past vast fields of rich ploughed earth heavy and black as chocolate. The Don Basin – rebel territory – is rich farming country, unexpectedly beautiful and golden as autumnal New England.

The next checkpoint boasts a full array of Donetsk People's Republic, or DNR, imagery. The tricolor black, blue and red flag borrowed from the short-lived Donetsk-Krivorog Republic which declared independence briefly in 1918 as the Russian Empire collapsed in revolution.

The newly-designed flag of Novorossiya, or New Russia, clearly modeled on the flag of the American Confederacy (Novorossiya is a Tsarist era term for the regions of South and West Ukraine conquered under Catherine the Great; it's now used by the Kremlin to describe Eastern Ukraine). And there's a blood-red flag with a Byzantine face of Christ in a gold medallion in the centre. One flag for Revolution, one for the Russian Empire, one for the stern God of Orthodoxy. We drive on, though a flat landscape punctuated with slag heaps and pithead gear.

Donetsk itself is eerily empty, though before the war the population was over a million. It was once one of the most prosperous cities in Ukraine. The Metro hypermarket on the outskirts is open for business – one of three surrounding Donetsk, of which one was looted in the early days of the war, along with the liquor shops. There are large billboards over the main thoroughfares advertising concerts which happened back in April which are just starting to peel.

For what is technically peacetime, there is a lot of shelling going on. A ceasefire agreement was signed by the Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko in Minsk in mid September, yet weeks later the sound of artillery rolls over central Donetsk all day and much of the night. Donetsk airport is still held by the Ukrainian army and the rebels bombard it furiously. The Ukrainians reply by lobbing artillery shells and grad missiles into the city.

In the distance the elegant, familiar glass-and-steel bulk of the new airport rises from a mist of autumn rain and gun-smoke. Underneath the airport is a warren of deep Soviet-era bunkers and tunnels left over from the 1960s. The airport's Ukrainian defenders retreat with their howitzers down into the bowels of the building when the barrages get too heavy.

Donetsk's main administration building is a vast, brutalist block which dominates a wind-blasted square. In the shelter of an overhanging concrete porch, a couple of dozen citizens queue up to enter. A rebel commander hears the petitioners out one by one and issues peremptory orders. "Go to office 210 and sign on to the queue. . . No, we don't deal with that yet, come back next week . . . "

The public areas are covered in spray-painted graffiti. A pair of patriotic lovers has written "Lena + Pasha = [heart] Russia!!!!" Volunteers – or perhaps mercenaries – from the Caucasus have also left their mark on the walls. "Chechnya is with Donetsk" says one inscription.

Sergei Fedorenko is a skinny young man who studied history at Donetsk university before signing up with the rebel administration as "a specialist on propaganda and agitation." He insists we repair to the men's toilets for a smoke. Despite the broken windows, ransacked offices and piles of charred paperwork lying around, the clean-living rebel leadership are sticklers for anti-smoking.

I ask him what the war is about.

"We don't want war but we have no choice. While the Kievans were jumping around their maidan waving flags, we in Donetsk were working. I was always pro-Ukrainian. But when they came to our lands armed and in anger then I decided I had to defend myself. All we wanted was the right to rule our own affairs. This is our own Maidan – except that we didn't send anyone to try to seize Kiev."

Back in the lobby the petitioners have been cleared well back as a bevy of rebel bigwigs arrive for a meeting. These men and their bodyguards have obviously spent a lot of time in front of mirrors perfecting their look. Leather fingerless gloves are in vogue, and US-issue rubber knee pads, green bandanas and wraparound sunglasses. The younger ones seem to be fans of Call of Duty. The older commanders channel Soviet war movies. They wear baggy breeches, leather webbing, tall black boots.

ONE NIGHT IN HAVANA

Night falls and the neatly-swept streets empty in advance of an 11pm curfew. Lights show in only a third of the windows.

I make my way to Havana Banana, a Cuban-themed basement bar. The interior design can best be described as Slavic Hawaiian. Donetsk's most famous author, Fyodor Berezin, arrives with an armed escort. Berezin has penned 22 volumes of futuristic military science fiction, which feature epic battles between a resurgent Soviet Union and decadent America. Since April, though, Berezin has served as the DNR's deputy defence minister. The author-turned-minister is in his fifties with a neat white mustache. He looks like an avuncular cross between Colonel Saunders and Colonel Kurtz. "When this war began I was asked, do you want to be a commander or a creator?" he says. "I could have run away to Russia in April but I decided no, I will stay and fight and try to create a new reality in the world, instead of just on a page."

Some of his views are eccentric. He believes that we all live in a Matrix controlled by a complex programme. He says that "fascism is an extreme level of liberalism," and sees what is happening today in Ukraine as all part of a slowly unfolding global conflict for resources.

"The Third World War began on 11th September 2001. At that moment, the Imperialists said, 'We aren't going to investigate who committed the attack,' No: instead, Imperialism decided that the natural resources are finite on this planet and we don't care with whom we go to war to get hold of them. That war began in Iraq, then moved to Syria and Libya and now they have come to Ukraine . . . Only Russia is a counterweight. Russia sits patiently with crossed arms and says, 'No!'"

Vast global wars are, I later discover as I read some of his works, something of a favourite Berezin theme. Uncannily, the cover of Berezin's 2009 novel, War of 2010. Ukrainian Front features an airliner being blown out of the air by surface to air missiles. In this prophetic book Berezin tells the story of a world war sparked by a conflict in Crimea.

Like many of his generation – he is two years younger than Vladimir Putin – Berezin is ambivalent about democracy and capitalism, and deeply regrets the collapse of the Soviet Union. "I agree that the Soviet Union killed many people in the 1930s. But the sacrifice was justified! Just look where we were in the 1970s – everyone had what they needed, no-one had to work much, everyone had leisure. So I see some historical justification for the 1930s. But I don't see any justification for what happened here in the 1990s. Now that was truly an unjustified genocide."

Now, with the formation of Novorossiya, he believes the opportunity has come to turn back the clocks to a Soviet golden age of decency and fairness.

"We smashed all the gambling machines by the side of the road," Berezin says proudly. "We dealt with the alcoholics and drug addicts harshly. We made them dig trenches for our troops. Before, they would just bribe the police – that won't be happening any more. Our model is that society has to come before individuals. We will not accept rotten Western values – we don't like same-sex marriages."

THE NEW FAT CATS

The demands of running a war economy dictate that all the property of businessmen and oligarchs who fled Donetsk must be confiscated. Despite the damage, the fighting has done to the region's pits and infrastructure, Berezin is optimistic that soon Donbass will be a "great metallurgical republic." All that's needed is the port of Maruipol, still in Ukrainian hands.

"Mariupol and Donetsk airport will be taken. We have only begun to fight. Our fathers broke the the fascists and ground them into dust. We will do the same."

At the Ramada Inn the bar is packed. In the far corner, in a special alcove, is an enormously fat man in a sloppy shirt and loose tracksuit trousers. His resemblance to Jabba the Hutt grows when he orderers a hookah pipe – all the rage in Moscow and now, it seems, in Donetsk. This man is a senior minister of the DNR, a successful local businessman in his previous life. His former bodyguards wear the uniform of Novorossiya, but remain his private army.

A romantic drama has been unfolding in the corner for some weeks. A bouncy, alarmingly blonde lady in her thirties, is the minister's good friend. She wears 80s-style high-waisted stretchy silver trousers decorated with sequins. Unfortunately, the bouncy lady's husband is also a prominent local boxer-turned-businessman with his own bodyguard posse. He is also one of the bosses of the DNR's prison service and sometimes shows up at the Ramanda. When this happens, wiser customers ask for their bills.

Tonight, though, the star-crossed lovers sit undisturbed. An aide rummages in a nylon bag full of Nokia telephones, all with labels taped on them: 'burner' phones. The DNR seem to have learned their security techniques from the The Wire.

"Meet the new bosses. Same as the old bosses," remarks an American colleague wryly. "There are three kinds of people in charge here. The old Soviet manager types. The local criminal types, old Yanukovych cronies. And the Russian military-intelligence types."

Only the second sort, the bandits, are in evidence tonight – honest Soviets like Berezin cant afford the $8 beers at the Ramada, and the Russians tend to be ascetic, sober fellows shy of running into journalists.

It is these local fat-cats who are the only real victors of Novorossiya's revolution. Certainly Russia has reaped nothing but grief from it, with Putin an international pariah and the economy poisoned in the root by international sanctions. Ukraine, too, has been literally torn apart economically and politically – though with more hope than Russia of emerging stronger from the experience. And the people of Donbass face a cold, hungry winter of fuel and food shortages, warmed only by nationalist rhetoric and empty promises. This revolution is a victory of the old over the young, of the stupid over the clever. It is a victory of the past over the future. It is history repeating as tragedy and farce at the same time.

Owen Matthews's ebook on his experiences travelling through Ukraine, Thinking With the Blood is available now from Newsweek Insights.