Great Read: Piatigorsky house is gone, but pieces of history were saved

The distress call came in early July from a longtime resident of Brentwood.

“The Piatigorsky house is being demolished,” she said. “We were their neighbors for 60 years.” Los Angeles was losing part of its cultural history, she said.

The two-story Colonial Revival house on South Bundy Drive had been the longtime home of the famed émigré cellist and USC master teacher Gregor Piatigorsky and his polymath wife, Jacqueline, a chess wizard, tennis champion and sculptor. Gregor had died in 1976 at age 73 and Jacqueline in 2012 at 100.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Piatigorsky house: An article in the Dec. 1 Section A about the legacy of Gregor and Jacqueline Piatigorsky and materials salvaged from their former Brentwood home referred to a monthlong exhibit of her chess archives at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis. The show ran for several months.

------------

In the combination living and music room that looked out onto the family’s orchards and garden, Gregor had played chamber music on many a New Year’s Eve with a fellow transplant, violinist Jascha Heifetz.

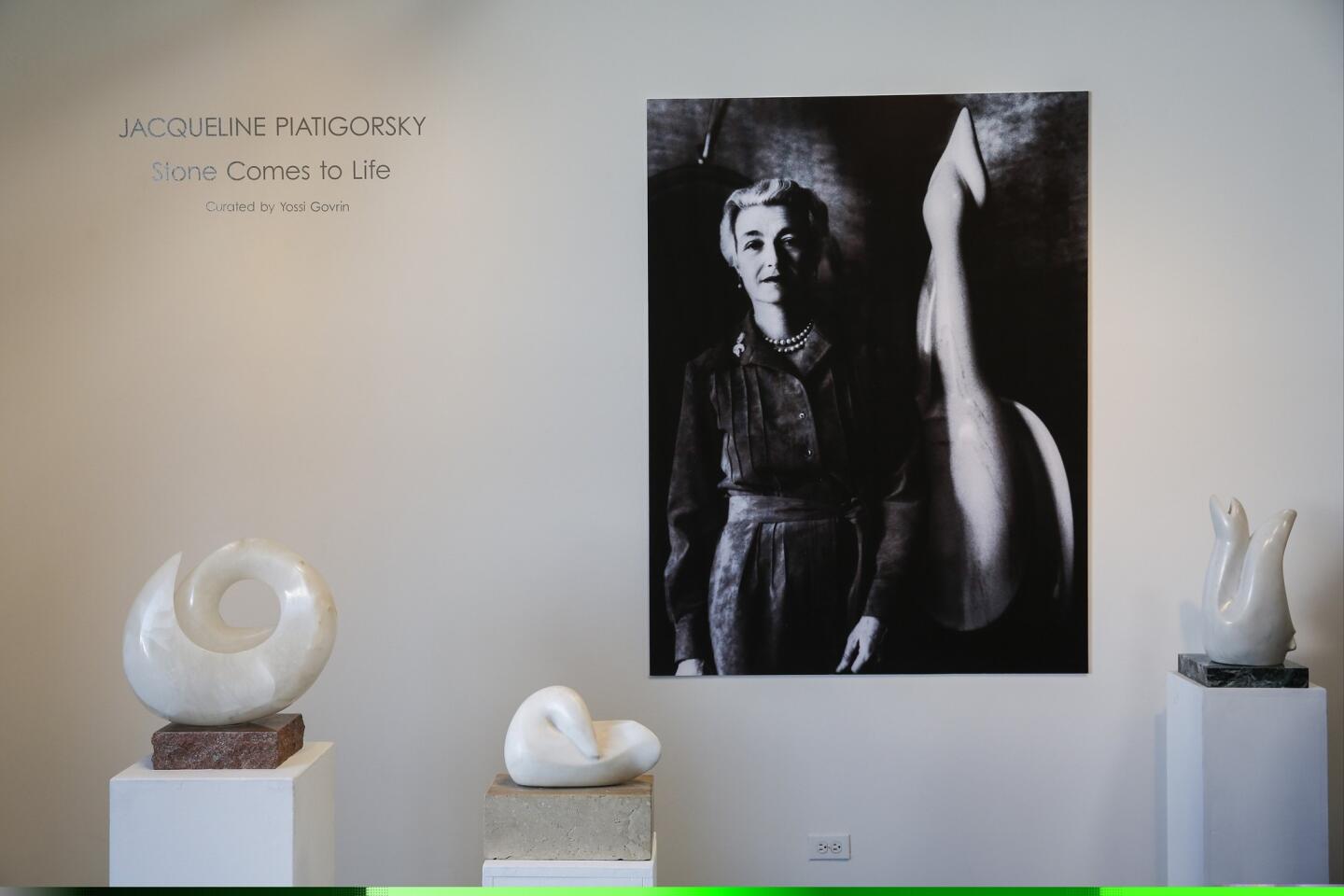

Jacqueline had carved elegant birds from blocks of alabaster and Carrara marble in a studio on the property. She had organized two legendary chess tournaments and welcomed international grandmasters into the home.

I felt compelled to investigate. When I got to the house, salvage workers were loading onto a truck the last of the vintage lighting, brass hardware, knotty-pine paneling and 33 tons of old-growth lumber they had stripped from the dwelling.

“Would you like this?” the man in charge said, fluttering between index finger and thumb a December 1955 New Yorker ad for RCA Victor Records featuring cellist Piatigorsky.

“We found some other stuff, too,” he said. “We were about to trash it.”

Minutes later, we were transferring from a wheelbarrow a 2-foot-high trove of dusty, musty Piatigorsky family ephemera — rodent droppings and all — into the back seat of my car.

Once at home, I carefully slid from their envelopes a few of the decades-old letters that the couple’s daughter had sent them. Jephta thanked her parents “for the Pontiac” and offered details about her courtship and marital bliss. The intimacy made me feel like a voyeur. The letters’ recipients were gone, but the offspring who had written them was still alive.

I stopped reading and went in search of the family of these two talented artists who, while living in their clapboard-sided house in Brentwood, had also mentored budding musicians and chess players and who, even in death, continued to hold sway in their spheres of influence.

::

He came from borscht; she, from lobster bisque.

She was a daughter of Baron Edouard de Rothschild (of the eminent banking clan) who grew up in a Parisian palace filled with paintings by Goya, Fragonard and Rubens. She was a poor little rich girl — neglected, repressed and emotionally brutalized by a pitiless nanny.

He was a Russian-born prodigy who at age 9 began helping to support his family by performing in cafes and brothels. At 12, after a dispute with his father, he was kicked out of his home into a frigid Moscow winter.

In 1921, he escaped to Poland and later moved to Berlin. He made his U.S. debut in 1929 with the New York Philharmonic, playing the Dvorak Concerto.

The concertizing cellist and the Rothschild heiress met in Paris through a mutual friend. They married in 1937 and had Jephta. In 1939, they slipped out of Europe just after France declared war on Germany. They lived for a time in New York state, then moved to Los Angeles in pursuit of better weather for son Joram, who suffered from ear infections. In 1949, the family settled into the Bundy house, with its spacious, sycamore-shaded front.

A dozen years later, Gregor and Jacqueline hired Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. and his son, Eric Lloyd Wright, to remodel what had been the dining room. The new music and living room featured a pitched roof, blond-finished ceiling beams and paneling, a fireplace of light-toned Palos Verdes stone and admirable acoustics. At the rear, light streamed in through angled windows.

Sometimes a cello student would arrive at 9 a.m. for a class and end up staying for dinner, as Gregor chain-smoked throughout the day. (He would die of lung cancer.) Mstislav Rostropovich, already celebrated, occasionally showed up to receive instruction from the elder musician.

Jacqueline dabbled in music — playing piano so-so and teaching herself the bassoon.

An Internet search in July turned up a bit of happenstance: A month-long exhibition of her chess archives was in its final days at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis.

Her fascination with chess had begun at age 6 when she was recovering from peritonitis and a nurse taught her the game. She represented the United States in the first Women’s Chess Olympiad in 1957 and competed in six U.S. Women’s Championships.

Through her sponsorship of two legendary Piatigorsky Cups, in 1963 and 1966, and her creation of the Piatigorsky Foundation — which offered chess programs for women, the elderly and public school students — she helped establish the West Coast as a center rivaling New York.

Gregor once said: “In the world of music, I am known as a cellist. In the world of chess, I am known as the husband of Mrs. Piatigorsky.”

::

It didn’t take long to track down Joram, a Caltech PhD who had a long career as an eye researcher and who lives in Bethesda, Md.

He was intrigued to hear about the overlooked materials and reminisced about his family’s time in Brentwood, vividly recollecting his first day in the house.

“The biggest surprise I had in my life was when I walked into the living room and saw this big box,” said Joram, 74, an emeritus scientist with the National Institutes of Health in Maryland. “It was a Philco TV. It was the first time in my life I’d ever seen one.”

In another instance of serendipity, Joram said dozens of his mother’s sculptures and drawings were to be displayed at Santa Monica Art Studios at the local airport.

At the Sept. 6 opening reception, I met him and his wife, Lona, and four of Jacqueline’s grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. (Jephta, 77, remained at home in suburban Baltimore with a broken hip.)

On display was a bust of Gregor that the family has donated to the Colburn School in downtown Los Angeles. Admiring it was Sel Kardan, a longtime friend of Jephta and the school’s president and chief executive.

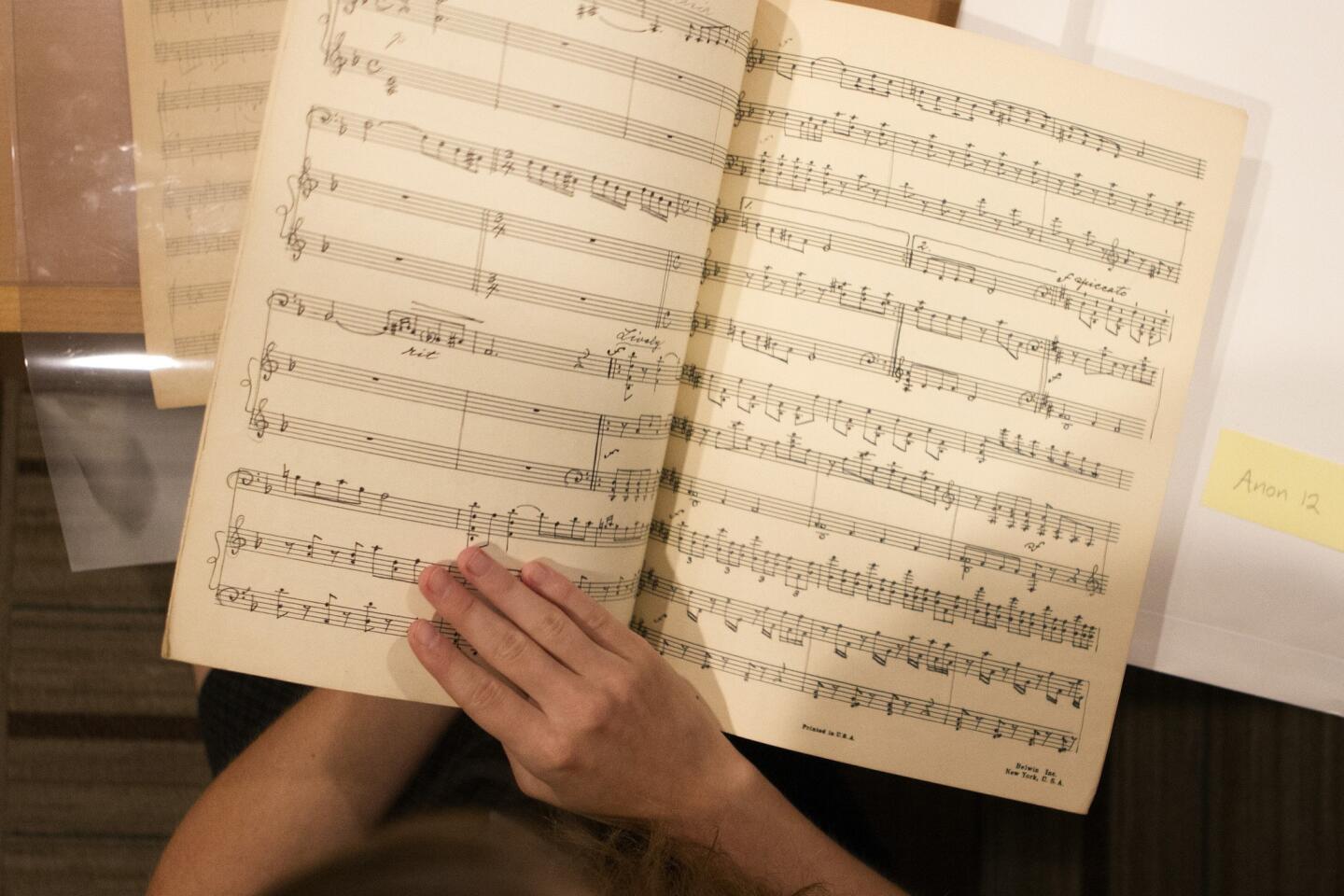

Since early this year, Colburn archivists have been inventorying 92 boxes of Gregor Piatigorsky materials, including orchestral scores, letters from fans and composers, tour itineraries, reviews, photos and drafts of his unpublished novel, “Mr. Blok.” Sharing a temperature-controlled room are hundreds of his commercial LPs, 78s, CDs and audiotapes.

Carol Merrill-Mirsky, the project director, studied at the USC music school and often saw the cellist on campus. “He was so well known and so loved,” she said. Now she is immersing herself in letters he wrote to Jacqueline while on his wide-ranging concert tours.

“The letters home are full of stories about missing the train or having to sleep in an upper berth with the cello,” she said.

Merrill-Mirsky and her team plan to digitize the materials once they have decided what’s most important to share with the world.

From the stack I turned over, the letters and birthday cards that Jephta and Joram sent to their parents will be returned to them.

The other items — including an 1896 Berlin printing of Dvorak’s “Concert für Violoncell mit Begleitung des Orchesters, op. 104” (Concerto for cello and orchestra), and an ancient piece by Saint-Saens — are temporarily stored in an acid-free box labeled “Martha Groves group for archives.”

Leafing through them as Colburn archivists watched, I found it awe-inspiring to gingerly finger music that Piatigorsky had performed. There was the crumbling Schumann he had played with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra in November 1960. The bio in the pristine concert program said: “It is unanimously agreed that the current cello renaissance owes its existence in large part to Gregor Piatigorsky.”

A yellowed front-page newspaper photo from Tokyo’s Asahi Shimbun, which sponsored his 12-concert Asian tour in 1956, showed a grinning Piatigorsky shaking the hand of a Japanese woman, who was bowing deeply. The cutline said in part: “The tall, handsome cellist, carrying his Stradivarius cello, was warmly greeted at Tokyo International Airport.”

Most poignant were the letters Gregor, with more than a hint of his strong Russian inflection, had penned to Jacqueline during that tour, from Tokyo, Hong Kong, Manila, Saigon and Singapore. Some were addressed in Russian to “my adorable Jacqueline.” One was scribbled on a Japan Air Lines menu. “The flight from Tokyo was fine only I did not sleep the entire night. ... I know how right it was for you and children to have stayed at home!!”

“I am very tired. Every city has chosen a different program. Can you imagine to play five programs!”

“I think of you without stopping. I love you with all my heart.”

In the midst of his exhausting two-month tour, the renowned cellist had poured out his feelings to the wife who awaited his return back in Brentwood.

The worried neighbor was not able to save any portion of the Piatigorsky house, but her summertime phone call did at least ensure that these revealing items — tucked away and forgotten for decades — escaped the Dumpster.

Twitter: @MarthaGroves

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.