What to do at Auschwitz? Hide site behind logs, Idea Office proposes

On a summer day last year Russell Thomsen walked through Birkenau, probably the most horrific place on Earth, not knowing what to think or feel.

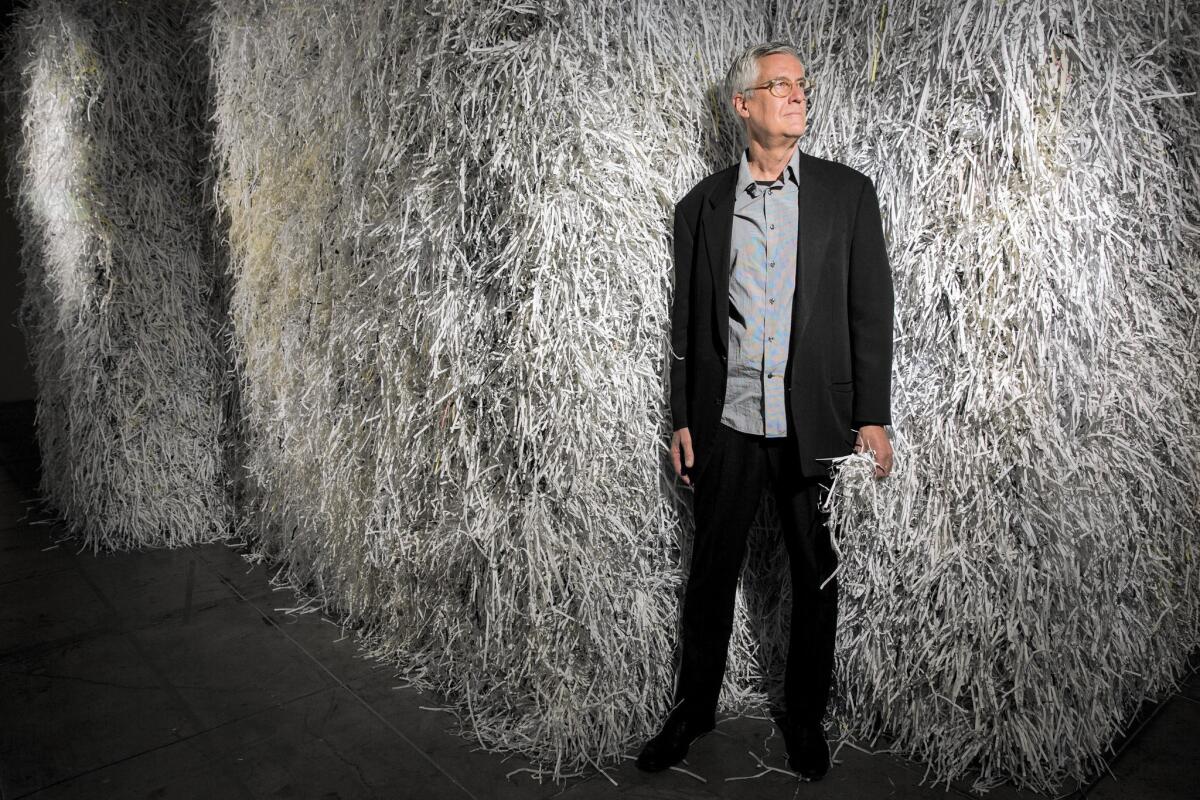

“It was incredibly beautiful, which is not something you expect,” the tall, silver-haired Los Angeles architect said. The Nazis knew the camp in the Polish countryside as Auschwitz II when they were operating it as history’s most productive factory of death.

Auschwitz I is the place most people think of when they think of “Auschwitz” — the concentration camp fronted by the gate inscribed with Arbeit macht frei (work makes you free), and where an estimated 300,000 victims were killed and then incinerated in a gas chamber/crematory complex that still stands.

Birkenau is a much larger and more barren place. The four crematories where 1 million souls rose to the sky in smoke are rubble — three destroyed by the Nazis as Soviet forces advanced, the other by Jews who rebelled in October 1944.

“ ‘Birkenau’ means ‘birch forest,’ and it’s very beautiful,” Thomsen said. “You see wild deer running through the camp. I wanted to feel something, and it was very difficult.”

But the visit confirmed for Thomsen that he could make a cogent case for the startling memorial that he and Eric Kahn, his late college friend and partner in the Idea Office architecture studio, had spent years thinking about and drawing up plans for — without anybody asking them to.

Their idea is to evoke the nothingness the death camp produced by removing Birkenau wholesale from that beautiful landscape.

Thomsen readily acknowledges that the memorial never will be built. It conflicts utterly with the official preservation plan being carried out by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, whose support foundation is nearing its goal of raising $150 million to create an endowment. The earnings will fund years of restoration of buildings at Auschwitz-Birkenau as well as conservation of documents, photographs and the belongings of vanished people that were found there.

For architects, Thomsen said, it’s worth thinking deeply about how to create emotionally charged structures, even ones that will never be more than drawings or models.

Idea Office’s proposal for Birkenau is on display through Dec. 5 in “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz,” an exhibition at the Southern California Institute of Architecture in downtown L.A., where Thomsen teaches and Kahn did until his death in June from a heart attack.

The first thing a visitor sees in the SCI-Arc library’s exhibition gallery is an 8-foot-high wall clad with confetti-like strips of white paper. It’s the front face of a fortress that shields what’s within. The white fort’s footprint is a miniature match for the Birkenau camp’s perimeter.

If the memorial were built, that perimeter would be a 30-foot-high wall of logs cut from trees from all the countries from which the Nazis deported people for extermination in the death camps. The interior, perhaps 40 acres, would be left alone, to be overgrown by vegetation as the decades and centuries passed.

In time — maybe 200 years? — the log wall would itself decay and tumble. Birkenau — or what time and nature had made of Birkenau — would be visible once again. And a new generation would face the challenge of what, if anything, to do to perpetuate the memory of Birkenau.

The design’s inspiration, said Thomsen, springs from the Torah, specifically Deuteronomy 13, part of a long sermon in which Moses lays down principles the Jews are to live under after they enter the promised land.

The chapter states the consequences for any Jewish town if it should reject God in favor of the pagan deities worshipped by neighboring peoples: every living being put to the sword, all property heaped in the streets and burned, and the site turned into a Tel Olam, Hebrew for “eternal mound,” never to be rebuilt.

Thomsen, a gentile, and Kahn, a Jew whose grandfather died in the Buchenwald concentration camp, discarded the religious wrath of the scripture but kept the basic concept of how to deal with a site where the utmost evil has been done.

The first spark, Thomsen said, came in the 1980s when the two friends visited the Dachau concentration camp in Germany. “It was bucolic, pristine. It had been carefully restored, and all the grounds were immaculate and clean,” he recalled. “The place felt staged and sanitized.”

Kahn visited Birkenau in the 1990s, rekindling the two friends’ discussions about designing a memorial. Flooding of the nearby Vistula River threatened the two Auschwitz camps in the 2000s, putting them back in the news.

Working more in earnest over the last few years, the Idea partners combed literature about memorials.

The Tel Olam concept came from a 1993 lecture by scholar Jonathan Webber, and the two architects found that there was ongoing debate over whether the mostly destroyed Birkenau should be restored to look as it did when the camp was liberated or left to be overgrown by the surrounding forest.

The Tel Olam struck Kahn and Thomsen as a “third way” that would provide a built memorial — that huge wall of leveled trees — but would also let the site eventually be reclaimed by nature.

Visitors would walk the perimeter, left to their thoughts. With the wall looming as a symbolic, visual presence, Kahn and Thomsen hoped visitors would become intensely aware of an invisible, lost presence — the camp within, and its million dead.

There would be no walkway outside the wall, only a path worn into the ground by visitors who had already come and gone.

Architecturally, Thomsen said, Idea Office’s Birkenau proposal has a kinship with recent memorials that mark enormous loss not with heroic statuary or traditional buildings, but by leaving a kind of void.

Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., is a gash in the earth lined with inscribed black stone walls and a walkway. Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is an array of more than 2,700 mute concrete slabs occupying a large plaza in Berlin.

“Reflecting Absence,” the memorial by Michael Arad and Peter Walker at the National Sept. 11 Memorial and Museum, preserves the two deep, rectangular holes in the ground left by the collapse of the World Trade Center’s twin towers.

But the International Auschwitz Council, which oversees the death camp sites, respectfully abhors such a void.

“The central tenet is to preserve and not destroy, so the stories of those who suffered and died there can live on,” said Mark Rothman, former executive director of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust who heads the U.S. branch of the fundraising campaign for Auschwitz-Birkenau preservation. “Preserving a site as authentically as possible allows for those voices, those whispers of history, to continue to be heard. You don’t hear anything from nothing.”

Some might think Idea Office guilty of incredible chutzpah — after all, who asked them? But Rothman, who hasn’t seen the L.A. architects’ plans but is acquainted with their concept, said it’s a worthwhile thought experiment.

“They are engaging in a conversation about preservation, a conversation about one of the most important sites in the world,” he said. “In terms of [furthering] a conversation, more power to them.”

For Thomsen, the official plan to restore Auschwitz-Birkenau to its appearance when the camps were liberated (nobody is talking about rebuilding the destroyed crematories) is “noble,” but faces long odds in the long run.

“We’re thinking in a much longer frame of time than our own lifetime,” he said. In fact, the plan calls for holding off on turning Birkenau into a Tel Olam for at least 30 more years, to avoid distressing any Holocaust survivors.

The next step, Thomsen said, will be to perpetuate the conversation by publishing “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” as a book, including essays by outside experts.

“Built or not built, architecture has the power to transform how we think about things,” he said.

------------------------------

‘Thinking the Future of Auschwitz’

Where: Southern California Institute of Architecture, 255 S. Santa Fe Ave., Los Angeles

When: Daily except Saturdays, noon to 6 p.m. Closed today-Sunday. Ends Dec. 5.

Tickets: Admission is free

Info: (213) 613-2200

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.