The inner life of Jawaharlal Nehru remains an enigma. The profusion of biographies and the occasional journalistic pieces, written when his birth anniversary made him the flavour of the week, will disappoint you if you are looking for his intellectual life. The focus there is on the public sphere and what Nehru did, not so much on his thoughts. And that is a tale often told. As a famous wit has said, we don’t know if history repeats itself but historians repeat each other.

Where do we look for the man’s life of the mind? One gets, of course, glimpses of it in Nehru’s autobiographical writings. And one gets it direct, unadorned by afterthoughts, in his private letters. Not all of those letters are open to researchers yet, but a good deal are. Most people dress up their thoughts out of the ideological wardrobe of their choice, as did Nehru sometimes in his mature years. But, if you read his letters, you might see that as a rule in his private communications he was not given to dressing up his thoughts like that.

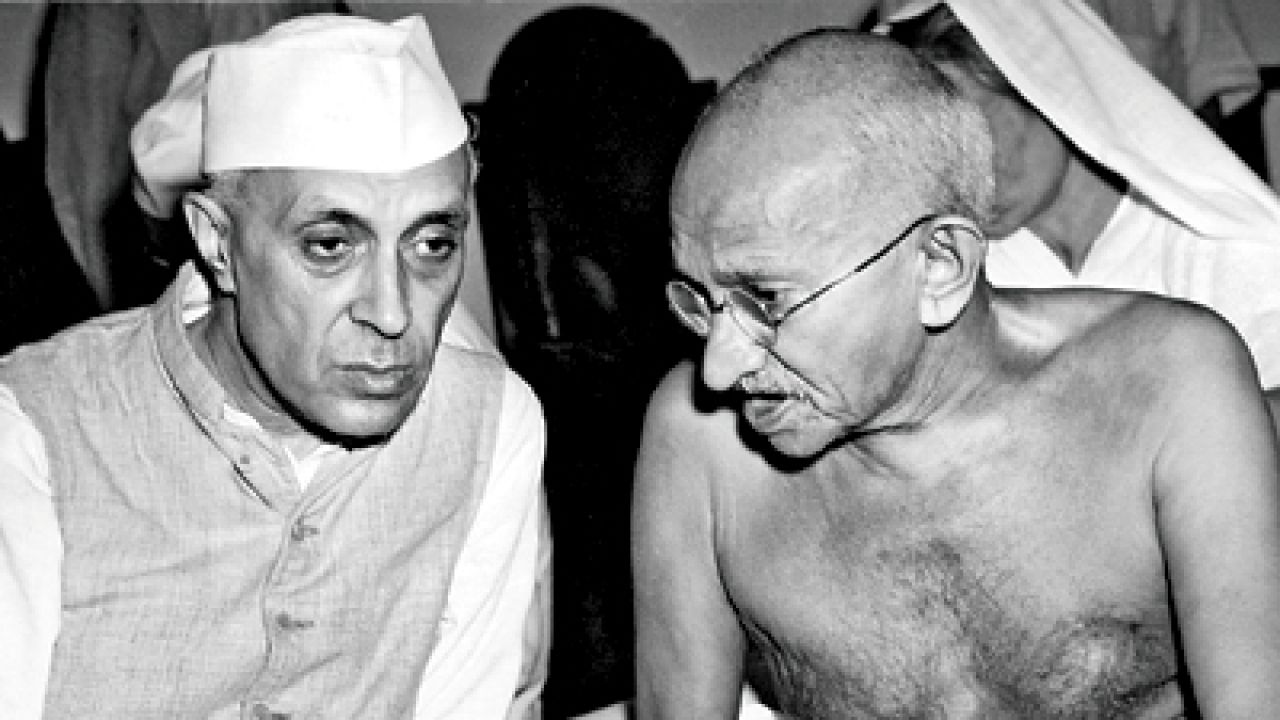

When we situate these letters in the context of contemporary history they speak to us in tones which ring true. They reveal to us moments of crisis, that is to say moments of decision, marking a turning point in his thoughts. We can learn more from those moments than the routinised expressions of thought which had settled into a groove in hundreds of his press statements and speeches and articles. Perhaps, one such moment came in 1945 when Nehru confided to Mahatma Gandhi in a series of letters his dissent from some of the basic premises of Gandhism. The debate between them about Nehru’s dissenting thoughts was hidden from public view. Yet, this crisis in the mind of the foremost follower of Mahatma Gandhi was crucially important and foreshadowed the policy that Nehru developed in the post-Independence decades. Another such turning point in Nehru’s thoughts and consequent political agenda occurred in the middle of the 1930s when the socialist activism of his younger days gave way to a stance of cautious negotiation with the Old Guard in the Indian National Congress. A third critical moment of departure from ideas cherished earlier was brought about by a huge blow to his vision of Asian and Third World unity and his slogan of Panchsheel and all that, during the border conflict with China in 1962. Of these three critical moments — involving Nehru’s approach to the Gandhian heritage, towards socialism and the Left, and to India’s interface with global politics — the first was obviously the most momentous in his intellectual life.

In October 1945 Nehru wrote more than once to Mahatma Gandhi expressing his scepticism about some basic tenets of Gandhism expounded in Hind Swaraj. Out of the reach of the public eye and the media, Nehru shared his critical thoughts with Gandhi alone. It is well-known that the first political tract that Mahatma Gandhi wrote was Hind Swaraj in 1909. Throughout his life he regarded this work as the definitive statement of his philosophy. Nehru’s critique comprised three kinds of argument. First, he thought that the book was dated and he made no bones about it. “It is thirty-eight years since Hind Swaraj was written. The world has completely changed since then”. Unless “present facts, forces” were considered afresh, the views developed earlier would be “divorced from reality.” (Nehru to Gandhi, October 9, 1945, Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, vol 14). Secondly, Nehru looked towards policies to be pursued in independent India — in fact when Nehru wrote this, Independence was less than two years away. Nehru raised the question how independent India was to protect herself “from foreign aggression, both political and economic” unless there was industrial development. Therefore opposition to ‘factory civilisation’ and idealisation of the village and cottage industry was unacceptable.

A third kind of argument Nehru used tends to push the criticism further into fundamentals. “I do not understand why a village should necessarily embody truth and non-violence. A village normally speaking is a backward environment”. Moreover, to keep pace with the rest of the world, India needed on the one hand “modern developments” and on the other scientific and technical advancement. “If that is so, inevitably a measure of heavy industry exists. How far will that fit in with a purely village society?”

Gandhi seems to have been deeply disturbed by Nehru’s missives. “I have said you are my heir. I should at least understand my heir and my heir should understand me. I shall then be at peace”. (Gandhi to Nehru, October 5, 1945; Collected Works, vol. 81). Exchange of letters between them was followed by Nehru’s visit to Gandhi at Juhu, Mumbai in November 1945 to discuss his questions further. There is no record of the discussion but it seems that the differences between them were not resolved because Gandhi writes on November 13, 1945: “If in the end we find our paths are different, then so be it. Our hearts still remain one.” Gandhi continued to maintain that “we shall have to go and live in the villages” where “the vision of truth and non-violence can be realised.” He continued to maintain that “factory civilisation” is built on exploitation and “exploitation is the essence of violence”.

To Mahatma Gandhi dissent from his leading follower was a blow, but he maintained his position undaunted. It is touching to see how anxious he was to convince his follower and ‘heir’. Very unusual are his words when he says: “My ideal village still exists only in my imagination. After all every human being lives in the world of his own imagination.” He was not persuaded to dismiss that vision. “If I were the only one left in the world who believed in it, I would not be sorry.”

One cannot miss the historical significance of the differences revealed. It was in Nehru’s intellectual life a critical moment of departure from his mentor’s world outlook, hitherto left unquestioned. Nehru’s letters reveal his inmost thoughts. And these thoughts eventually led to the policies which Jawaharlal Nehru pursued as the Prime Minister after 1947.

This is the first of a two-part series on Jawaharlal Nehru

The author is formerly professor at JNU, and Chairman, ICHR, New Delhi, and Vice-Chancellor, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan. His most recent book is The Defining Moments in Bengal, 1920-1947 (Oxford University Press, 2014)