Every American road trip is different; thus every American road trip book is, and should be, different from every other. The beauty of such books done well has much to do with the nature of the country itself: so enormous and diverse, and so (if we're honest) contingent and arbitrary in its history and geography, that any trip across or around it is bound to have as much to do with the personality of the road tripper, and the happenstances inherent in the act of traveling, as with any putative qualities of the vast abstraction that we call America. This is as it should be.

Still -- and regrettably -- any of us who drive around America and write a book about it do so in the long shadow of a very famous writer's very famous book. Reflecting on his own planned trip in his prologue, John Waters makes the requisite reference, though he makes it with an admirably critical eye and purpose:

Or could I just make up the whole book and say it was true? How would anybody know? It took years for scholars to figure out that John Steinbeck's supposedly nonfiction Travels with Charley: In Search of America, a well-reviewed bestseller published in 1962 (and still in print), was in fact total bullshit. Instead of driving cross-country in a pickup, staying in campgrounds, and chatting up the locals, as the author claimed, he actually had company with him, stayed in motels and luxury hotels, and made up the conversations. According to writer Bill Barich, quoted in a recent New York Times article, Steinbeck was "discouraged by everyone from making the trip." He was too old, "trying to recapture his youth, the spirit of knight-errant." Uh-oh. Could that be me?

But before I tell you how wonderful Carsick is, which it is, I'm compelled to take Waters to task for a sloppy reading of the New York Times coverage of the unmasking of Steinbeck's fraud. Bill Steigerwald, the man who busted Steinbeck, is a friend of mine. And the reason he's a friend of mine is that, after reading the same April 2011 Times article that John Waters read, I was so impressed that I made a point of stopping in Pittsburgh and taking Bill to lunch on my own drive around America for my book Home Free. Bill deserves credit for a genuine mighty feat of reporting, and he rightly seizes every opportunity to claim the credit that he deserves. It wasn't the New York Times, and it certainly wasn't the cozy coterie of scholars Bill dubs the Steinbeck Studies Industrial Complex, who painstakingly read the original manuscript of Travels with Charley at the Morgan Library, then doggedly drove around America and documented Steinbeck's specific failures and evasions in a wonderfully entertaining book aptly titled Dogging Steinbeck. It was retired Pittsburgh newspaperman Bill Steigerwald who did those things, and no one else.

So I hope that Waters sees fit to give Bill due credit in future editions of Carsick. That said, Carsick is a wonderful American road trip book in its own right. Apropos the passage quoted above, it really is three road trips in one: two fictional, one real. The book's first section imagines "The Best That Could Happen," the second "The Worst That Could Happen," and the final section relates Waters's actual trip. Waters would no doubt be amused to learn that a friend of mine (who is gay, which is relevant to much of the subject matter) read the prologue inattentively and got almost through the first section before realizing -- or rather being told by me -- that it was made up. The first two-thirds of the book is no less enjoyable for being fictional; in fact, both the "Best" and "Worst" trips are jaw-dropping, page-turning exercises in imagination (both sexual and otherwise).

After all the shocking and appalling made-up misadventures, it's a relief to read about Waters's actual trip, which was plenty adventurous enough for a man of 66, especially when you remember that Waters didn't even drive but hitchhiked. Bill Steigerwald traveled at a similar age and also, as he puts it, doglessly. I agree with Steigerwald's dictum that, if you're planning to make an American road trip and write a book about it, you shouldn't take either your dog or your wife (or, if we must be explicitly gender-inclusive, your husband). What Steigerwald means is that traveling alone helps you stay alert. Steinbeck took both (though only his talking pedigree French poodle appears extensively in his bad book). The journalist and novelist Philip Caputo, well known for his classic Vietnam book A Rumor of War, took his wife and two dogs in a vintage Airstream trailer, and the effect in his 2013 book The Longest Road is of spending a very long evening at the senior center watching the vacation slides of a kindly but self-involved and dull retiree couple.

Caputo's whole conceit is that the same flag flies over Key West, where he and his wife and dogs started their trip, and Nome, where they ended up, and isn't that swell, with precious little reflection on how that fact illustrates that the United States of America is, effectively, an empire. My own very different summing-up at the end of Home Free is that "while the United States, plural, might be in some sense a single country, they are also an archipelago of disparate communities. Whether the center would hold was an open question."

Caputo's book is not fraudulent like Steinbeck's, but it is dreadful. Both show that being a famous writer doesn't suffice to write a great, or even good, American road trip book.

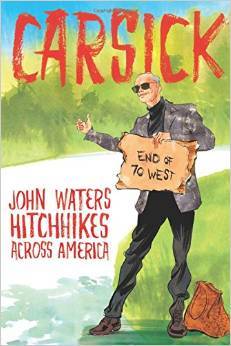

Carsick is a triumph because Waters had sufficient humility, sense of humor, and perspective on his own fame to turn it from an obstacle into a literary device. Throughout the book he frets alternately about whether he will or won't be recognized, and he carries -- and once or twice makes use of -- an actual "fame kit" that he had his staff put together for him. "I just signed a book deal resulting from the shortest pitch ever," he informs us at the beginning. "I, John Waters, will hitchhike alone from the front of my Baltimore house to my co-op apartment in San Francisco and see what happens. Simple, huh?"

The happy paradox is that it's precisely by maintaining a light touch and not taking himself or his quixotic project too seriously that Waters has written what might well be something of a minor masterpiece. "The CHECK ENGINE light continues to add a touch of anxiety," he writes somewhere in the desert in Nevada, near the end of the real trip, "but we've risen above that -- just that we're still moving is proof we're okay."

I could quote endlessly from Carsick, which tells you something. Enjoy it for yourself. Among its greatest pleasures are the many paragraph-length gems of narrative whimsy, so true to the reality of American road-tripping (and so very different from anything either Steinbeck or Caputo offers). Here's just one from Waters, temporarily stranded in Bonner Springs, Missouri:

I see the dreaded Holiday Inn but don't go near it. I stumble into a convenience store and buy two giant bottles of Gatorade and another bottle of Evian. Exiting, I spot a Taco Bell, the only fast-food joint I'm ever tempted to patronize in my real life. I enter, plop down my even heavier bags now that the liquids are inside, and get in line to order. I flash on Lana Turner, who, her daughter Cheryl Crane once told me, was an early financial backer of Taco Bell, and think how I couldn't be any further away from Hollywood glamour than right now. All the normal people on their lunch break look like aliens to me. I'm almost jealous of their lives. I order two tacos and sit by myself in a booth awaiting my number to be called, hoping to be recognized, but customers just stare back at me blankly. I guzzle down an entire bottle of Gatorade, then another. I feel like sobbing as I walk up to get my order but control myself, sit back down, and eat my tacos. With lots of hot sauce, they're pretty tasty. I hope Lana Turner's estate made a small profit.