The Louisiana state penitentiary is called Angola. It is named after the plantation that once stood there, which in turn is named for the homeland of some of the African slaves who once worked on it. Henry James spent 30 years of a life sentence for rape there before DNA evidence exonerated him in 2011. His story is the subject of a documentary film created by artists Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick as part of the third Prospect biennial in New Orleans.

The event—running until 25 January 2015—is the most racially diverse contemporary biennial in US history. Twenty-two of the 58 participating artists are African-American, and 44 are artists of color. These kinds of statistics shouldn’t be so unusual, nor should the kinds of conversations the organizers of Prospect want to encourage, about race, social anxiety, crime and punishment. But in America, they are.

The issues the artists raise are not new, but recent years have made some of them either more acute, more visible, or both. The forced slave migration that founded New Orleans created its historical problems, but these have been freshly compounded by the dismantling of longstanding communities in New Orleans, ravaged first by Katrina and then again by gentrification. Rise income inequality since the economic recession has caused greater poverty, which disproportionately affects African-Americans. Poverty and crime have long been bedfellows, but the scale of the privatized, profit-making prison system is unprecedented—and it too unfairly impacts African-Americans.

These are especially tough topics in New Orleans, where poverty is even more a racial issue than in much of the country. Unemployment rates for African-Americans, especially males, hover around 50%. Income inequality is growing faster than in most other places in America: Despite recent economic growth (thanks to $120.5 billion of federal aid after Hurricane Katrina), the poorest 40% of New Orleans’ population generates just 7.5% of its overall income.

And these local problems resonate further afield. The city of St Louis, Missouri, remains on edge as it awaits the imminent decision by a grand jury on whether to indict the policeman who shot dead Michael Brown, a young unarmed black man, in Ferguson this summer.

In that setting, three of the exhibits at Prospect offer a particularly pointed perspective on race and migration in America.

Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick

There are more than 40,000 people in Louisiana jails today. The state has the dubious honor of being the world’s prison capital, with an incarceration rate (including people awaiting trial) that’s over double the US average and almost five times that of Iran, 13 times that of China, and 20 times that of Germany. African-American males are disproportionately affected: one in 14 black men from New Orleans is in prison, and one in seven is either behind bars, on parole or on probation, according to The Times-Picayune newspaper.

“We are living in times that are really scary for our people,” Calhoun says. “Slavery never stopped, thanks to the prison industrial complex. This whole town depends on incarceration.”

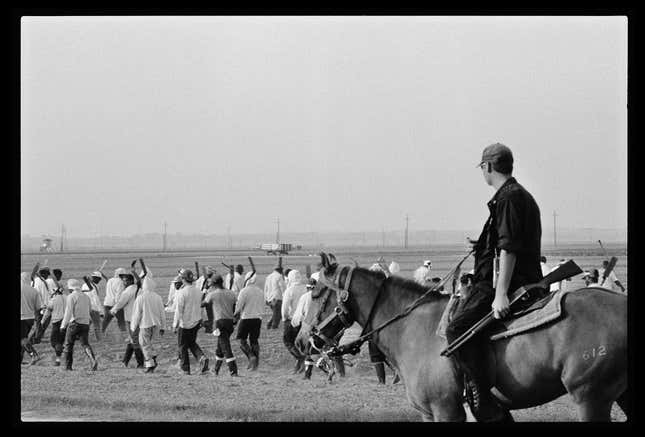

He and McCormick, his wife and collaborator, have been documenting life in Angola, and the plantation mentality behind the prison system, since the early 1980s. One of the photographs in the show, which is at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, is called: “Who’s that man on that horse? I don’t know his name, but they call him Boss”. It shows a white man on a horse, toting a gun as he oversees prisoners picking cotton. It looks like a pre-Civil War picture, but was taken in Angola in 1981. “The men are performing back-breaking field labor, while being guarded by white men with rifles on horseback. It’s a clear depiction of slavery,” McCormick says.

“There is a race problem in this city, and people who say there’s not are in denial,” she says. “They don’t want to confront their foot on someone else’s neck.” The problem extends beyond Louisiana, Calhoun adds: “What’s happening in Ferguson is a clear example of what could happen with military force.”

Tameka Norris

In the feature-film length installation Meka Jean: How She Got Good, the artist Tameka Norris attempts to navigate identity in post-Katrina New Orleans through her alter ego, Meka Jean.

Norris, a former rap artist, was raised on the Gulf Coast but moved away for college, returning to New Orleans after Katrina. Her work questions the ways in which her body—its color and gender—is perceived in various social scenarios: as a successful artist taking part in a radio interview; shopping at Walmart in a predominantly working-class area; naked and crying in her shower. “What does it mean to see this body playing golf, or to see this body twerking? What does it mean to be a person of color straddling two worlds? Most times people don’t see me as an academic, privileged or Yale-educated. They just see me as a black woman,” Norris says.

Her work for Prospect is on show at the May Gallery, a run-down warehouse space in the Lower Ninth Ward, the neighborhood in which she lives and which is perhaps now best known for the devastation it suffered after the storm. Norris deliberately picked a venue outside the main tourist hub, though the location itself reveals some of the social prejudices within the city—my taxi driver visibly stiffened when I asked him to drive me there, and left the engine running while I went inside to see the show. “A ton of people living in New Orleans have no idea that there’s an art show going on. The biennial itself is about access, and who in society has that?” she says. “Who doesn’t want to see change? But it’s hard to know what that would look like.”

Tavares Strachan

An enormous pink neon sign that reads: “You belong here” is mounted to a barge floating on the Mississippi. It is a work of art created by the conceptual artist Tavares Strachan with the deliberate intention of being misleading, he says. “It seems like a very friendly statement but it’s really asking a lot of difficult questions: Who are you as a person? Do you belong? Who gets to determine whether you belong? How do we define here, and what does it mean to be in a particular place?”

While the work resonates in New Orleans—“you can’t overlook the site-specificity. This is a city that’s seen a lot of struggles,” Strachan says—he hopes for a broader interpretation of the work. “There is the larger issue of migration. A lot of the politics of a place come from where we build cities, and where we decide to call home.”

“The strength of art is that it has the ability to create a new language structure,” he says. “Why do any of us belong anywhere, really?”