New dating sites show up online almost as often as Kim Kardashian's ass. One day it's Tinder and OKCupid. The next, you've got Clover and the League and Project Fixup and Zoosk—names that sound like the members of a teenage Swedish rap group.

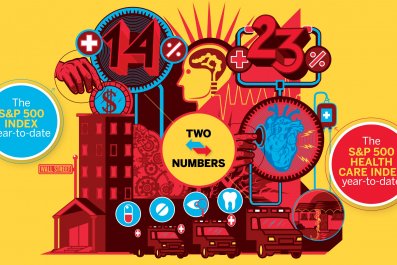

We so far haven't seen a Google or Netflix of online dating—no one company that has nailed it and run away with the category. And in technology, when a constantly changing gaggle of companies contend for pieces of the same market, it almost always means one thing: None of them are getting it right.

But that should change. Google and Stanford University just announced a breakthrough in computer vision, and it eventually could let a Tinder-like dating app learn what you find attractive in a person's appearance. It's not outrageous to trace a line from experiments today on dating sites to coming machine-learning systems that will be able to make better matches than a neighborhood yenta. Whoever gets this right first could dominate the market.

On one hand, it might seem odd to claim that online dating is broken. Some 20 million users visit a dating site each month. Match.com has 29 million members. Tinder is growing like crazy. If you've been married for 20 years and are reading this, you might feel as if there's an orgy going on out there that you weren't invited to.

Plus, dating sites have an incentive to avoid being too good. If they quickly find you a match, you then quit the site. (Or so you promise.) It's like the quandary dentists must feel when they give their patients fluoride treatments.

Dating sites today are just marketplaces. Over the years, many have purported to use algorithms to guide users to better matches, but none have improved the odds much. The algorithms that refine Google or capture more of your money on Amazon choke when applied to the complexities of attraction. Even the master of dating data, OKCupid co-founder Christian Rudder, is skeptical about algorithmic attraction. "One person doesn't kick out enough data to hone it down," Rudder tells Newsweek. "Someone will look great on paper and then have an annoying laugh." So, he adds, as in any vibrant marketplace, "the most important thing for a dating site is to have a lot of people."

To even try to apply algorithms to dating, sites have needed members to fill out questionnaires or maintain profiles, which many consider annoying time-sucks. Tinder is actually anti-technology—a rejection of computerized matching in favor of reptile-brain instantaneous reactions to images. Or there's Tawkify, co-founded by Elle sex columnist E. Jean Carroll, which has gone back to the ancient practice of using human matchmakers.

How could technology do this better? Let's start with one of the newer dating apps, the League, whose slogan is "Date. Intelligently." It supposedly limits its membership to "elite" people. It determines how elite you are and finds matches by connecting to and analyzing your LinkedIn profile. In other words, the League learns a little about you through one very narrow lens.

It's a short leap from there to a dating site that could tap into other online activities to learn even more about you and whom you might like to meet. How about Netflix movie ratings? In my case, any woman who gives ¡Three Amigos! one star would never be a match. Spotify playlists would add taste in music—often predictive about matching personalities. Foursquare check-ins would say a lot about places you like to go.

Want to really go down this rabbit hole? Let the dating site look at your Amazon purchases. Or Google searches. Then you'd be standing naked in front of the online mirror.

Today's computers and algorithms would have a tough time analyzing all those data streams to understand individual members. But researchers are inventing a new generation of computers based on the way human brains work. Instead of processing data through algorithms, these machines can watch data streaming past and see patterns. One of the first such products, from Numenta, watches activity for Amazon Web Services and looks for patterns that can give early warning about a hacker attack—patterns no human could ever see. "Our systems are like brains at birth," says Numenta founder Jeff Hawkins. "They just learn from the stream. You don't have to tell them anything."

These machine-learning systems could build something of a computer model of you. This is a far cry from an online profile, which doesn't always include the truth about, say, weight or salary or the fact that you're a 30-year-old rugby player who secretly listens to Taylor Swift. It would model you the way supercomputers model the weather and be able to make predictions about future behavior.

Another step will be to apply machine vision to analyze Tinder-style swipes. The Tinder app works by flashing photos of potential matches. You swipe left for no and right for yes. Many Tinder users swipe through hundreds of images a week. Tinder doesn't learn anything from that activity—it doesn't come to understand what physical features you like and which ones you instantly trash. But with advances in machine vision, it could.

Then the system would have a model of you and a sense of what you like in a person. It would also, of course, have similar models of potential matches, and could start looking for connections that might work out. Such a service should be at least as good as getting set up by a best friend.

Eventually, dating systems based on machine learning might let people avoid dating altogether. My data will be able to meet your data, and we'll find out if we're destined to fall in love and have two kids and a Land Rover and then get divorced, before wasting time on some awkward first-date dinner.