London's Masterchefs

India is a familiar flavour in England but top chefs and restaurateurs are giving it a novel spin.

Bruce Palling

Food & Wine Columnist

We are all about sharing big, bold flavours and food that is accessible to all kinds of palates and levels of the market. People from India actually seek us out because it reminds them of "ghar ka khana" Karam Sethi Gymkhana

What is going on with Indian cuisine in London? It is not just at the popular level that Indian cuisine has taken off in London. Gymkhana, which celebrates the cuisine of the Raj clubs of the subcontinent, was recently voted the top restaurant in Britain in the National Restaurant Awards, Restaurant magazine's annual count down of the top 100 restaurants in the UK. It also got its first Michelin star when the new list was announced at the end of September. A few years earlier, Trishna, which is owned by the same proprietors and specialises in west Indian coastal cuisine, got a Michelin star. The latest Michelin Guide to Britain has seven Michelin-starred Indian restaurants in London alone, which is second only in numbers to those for French restaurant.

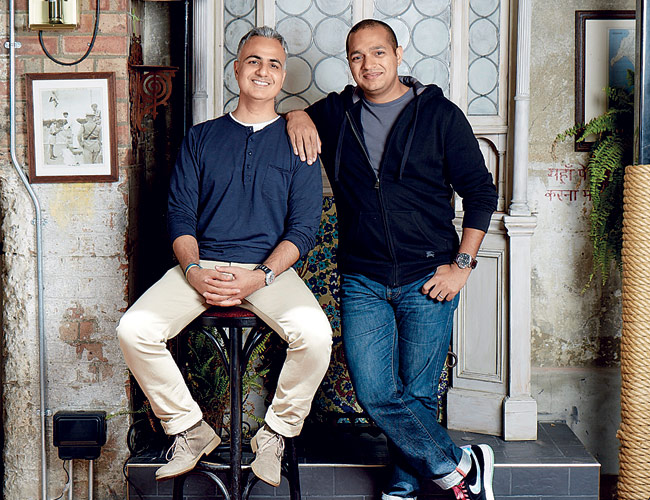

The Gymkhana phenomenon is extraordinary. Located in the heart of Mayfair, it serves dishes which are authentically spiced, which means they might challenge the palates of most of the non-Indian patrons. One of the most popular dishes is kid goat methi keema, which for a small charge, can be accompanied with bheja or goat brains. Gymkhana has been embraced by critics and everyone else and it is impossible to get a reservation for weeks on end. The Times food critic gave it a perfect score and went three times in five days to try more dishes, while others have shown similar pop star like fervour. Karam, 31, is the chef-proprietor of Trishna and Gymkhana, along with his brother Jyotin, 35, who looks after the business, and sister Sunaina, 27, the sommelier for the group. The Sethis are also involved in several European restaurants, two of which have recently won Michelin stars. Although all of them were born in Britain, their parents emigrated to London from India in the 70s and they all maintain close ties with the subcontinent.

Karam spent a year working in the kitchens at the ITC Maurya in Delhi, including the famed Bukhara, and longer at Zuma, the Japanese influenced restaurant in Knightsbridge which has been replicated all over the globe by chef Rainer Becker and his Indian backer, Arjun Waney. "Everything I do stems from the home cooking of my mother, especially the style and level of spicing. I was also influenced a lot by Rainer Becker and his philosophy of sharing plus never having too many ingredients on the plate," says Karam. There was also a desire to expand the repertoire of ingredients.

"When we started Trishna in 2008, there probably wasn't a single Indian restaurant serving seafood other than sea bass or prawns on their menu. We were serving langoustines to scallops to cockles and even whelks. With Gymkhana, it was more influenced by the food I had eaten in India like Bukhara and the kebabs, or at the Delhi Golf Club, which has a great terrace where they have plates and plates of kebabs, which you eat with a beer and then finish with a dal and a biryani," he says. That style of eating influenced Gymkhana in terms of the informality. It also chimes in with people wanting to have a selection of sharing dishes in the middle of the table rather than a starter, main course and dessert. "We have always done that from day one, sharing big, bold flavours and food that is accessible to all kinds of palates and levels of the market. People from India actually seek us out because it reminds them of "ghar ka khana" (home cooking), without fashionable fusion, swipes, swirls, cresses and all of that," adds Karam. The menu at Gymkhana allows you to share plates and also gives you the options of a la carte dining and set meals.

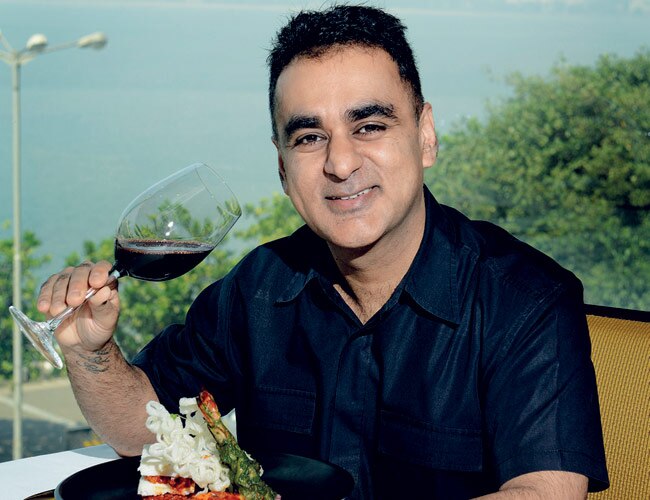

Much before Gymkhana became a rage though, Indian food had found favour in London. It becomes impossible to talk about the evolution of Indian cuisine in London without referring to Vineet Bhatia, the man who is known for creating dishes with sophisticated spicing and one of the first Indian chefs to gain a Michelin star. Rasoi, his townhouse restaurant in Chelsea, has been around for a decade. This is probably the most rarefied Indian cuisine in London, with unerring accuracy regarding the spicing but taking on a distinctive western appearance on the plate. "Innovation has always been my focus. From mulberry kheer to violet jalebis, I am constantly playing around with different combinations of Indian spices and racking my brains as to how to present great Indian food in new ways. My effort has been not to offer the predictable samosas and tikkis in the menus. I have always tried to think out of the box and offer a completely new gastronomical experience such as roasted lobster with broccoli khichdi. It's all about staying connected with my roots, exploring our rich culinary heritage and presenting it in a contemporary fashion."

Atul Kochhar, one of the first Indian chef to gain a Michelin star, is the chef-proprietor of Benares in Mayfair and the godfather of innovative Indian cuisine in London. Some Indian based critics accuse him of virtually inventing "Frenchified" Indian cuisine, a charge which strikes him as absurd. "There are 36 distinctive cuisines within India so it is impossible to talk in a singular sense about Indian cuisine. It is as ridiculous as suggesting that all food in Europe is similar because everybody uses salt and pepper," he says. This is a thought echoed by other chefs as well.

He adds, "The idea that including non Indian influences makes cuisine inauthentic comes from within India. Those critics forget that there are tens of millions of Indians who live outside the country and have a very different point of view. I am cooking for them and Europeans, not people living in India and I certainly don't believe I am doing anything wrong. In Bengal, he points out, people like eating fish head curry but if you gave it to a Punjabi, he would revolt. He doesn't call it Frenchifying, he calls it using different techniques. If you cook some meats sous-vide, it enhances the flavour. It may not gel with Indians in India, but as he says, he is not in India. He is a big fan of tradition but not of authenticity, as that is time-bound. "If my forefathers ate meat that was overcooked 10 times, that is not something I want to follow," he laughs.

Vivek Singh and his Cinnamon Club, just around the corner from the Houses of Parliament, occupy a different niche. This is wellcooked westernised Indian cuisine that will not frighten the horses or the Members of Parliament who frequent it in session. Again, it arrives at the table fully plated but many dishes would be considered western, such as the venison or lobster tail dishes if it wasn't for the Indian spicing. "We describe our cuisine as evolving modern Indian using traditional techniques combined with the best local produce, wherever in the world we are cooking. We create a marriage of old and new, east and west," Vivek says. He must be doing something right as the Cinnamon Club serves 350 people on a busy night, which could well make it the highest grossing Indian restaurant in London, if not the globe.

One influential Indian chef in London who because of his modesty is almost beneath the radar, is Sriram Aylur, chef and director of operations at Quilon. It specialises in Indian west coast cuisine and has held a Michelin star for eight years. Sriram is also director of Bombay Brasserie, the Indian restaurant that was the first to be embraced by the social set when it opened 30 years ago in Kensington. He is not surprised by the Michelin stars held by Indian restarants in London as he believes that the city has the most informed audience for Indian cuisine outside of the subcontinent.

"You can't dish out just anything in Indian restaurants any more because chances are that many of your clients will have travelled to the region you are specialising in." He will not be drawn on the traditional vs. avant-garde argument. "I cook using both classical and progressive techniques but regardless of this, everything has to come from an Indian ethos and the seasoning used must not be simply from India, but the west coast of India, such as mustard, curry leaves, tamarind, cumin, coconut and five or six different types of chili I use in my kitchen. When we create new dishes, they should feel like they had always been there." Sriram thinks the future of Indian cuisine in London is in regional cuisine. "Central India and the east coast have a lot to offer. Gujarat and Indore are interesting, as is Lucknow, providing it can be cooked in a way that is relevant to the current times."

And it is not just at the high end that Indian cuisine is making a mark in London. Michelin stars aside, restaurants rooted in Indian food aesthetics, like Spice Cafe Namaste have quite a cult following. Cyrus Todiwala, the chef / owner here creates fiery Goan dishes at his outpost. He says, "International diners who seek just Indian food might find themselves in one of the 10,000 curry houses in the city. Yet, we have seen a rise in French, Belgian and American tourists in London who are discerning and looking for a culinary experience that is exceptional. He adds, "Cafe Spice has never tried to get a Michelin star. We are proud of our flavours and style of cooking and our hearty portions.

We choose to focus on that rather than to poncify food and make it all about how it is plated, what it looks like. There are people who are specifically after these bold bursts of flavour and are not interested in the drama that often accompanies modern Indian cooking, especially overseas."

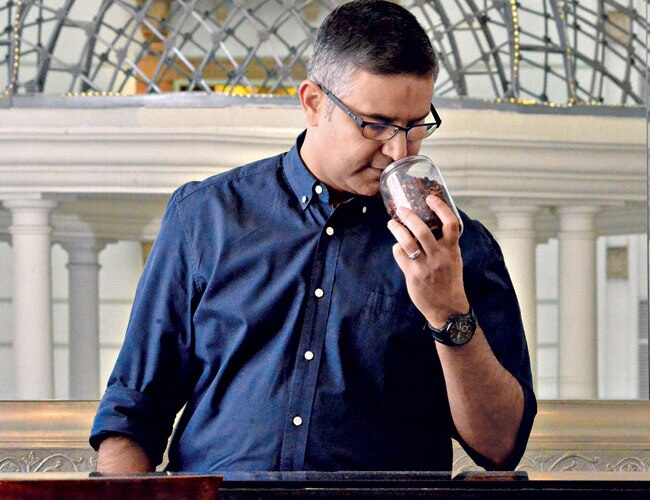

One can't discuss the Indian food explosion in London without talking about Dishoom. Behind the revamped Kings Cross and St Pancras Stations, there is a huge development around Granary Square, which was once the transit point for rail goods before they went on their way either by road or canal in the late nineteenth century. The former stable building on this 67-acre site has been transformed into the largest Indian restaucyrus rant ever to open in London, the brainchild of Shamil Thakrar, who re-invented the Irani restaurant concept and called it Dishoom.

There is space for 250 diners over several levels and more than 90 people can be accommodated at the marble-topped bar, which serves barrel aged cocktails. Hardly any non-Indian Londoner had even heard of Irani cafes before Dishoom opened in Covent Garden four years ago, but now they become an integral part of the kaleidoscope of Indian cuisine. The second branch, which opened in fashionable Shoreditch, has two hour queues at weekends.

"There was no one with an agenda to cook people's food. If you say the word Indian most people will think of either Bollywood, cricket, or a curry house. We have a different ambience squarely located in Mumbai which is a mad sort of place with a multi-ethnic texture, which I wanted to celebrate, along with the high Gothic style of the Victorian era," says Shamil. 'We want everyone who comes in, which includes Lakshmi Mittal, David Cameron and Russell Brand, to be seated next to a cool hipster or a poor student. For me, it is very important to have a space where people can enjoy great food which isn't court cuisine or rarefied food."

With all of the interest and attention to Indian cuisine in all its many guises, the future is bright. After all, there are still numerous Indian regional cuisines and techniques that are yet to be found in London and it would be a brave person who predicted that more won't be arriving here before too long.

Follow on Twitter @Bruce_Palling