Before Us Weekly and People, there was Elio Sorci.

Sorci was among the very first “paparazzo,” a term coined by Federico Fellini for his film, La Dolce Vita, to describe a small band of press photographers who documented film production in Italy in the 1950s, when studios like Cinecittà were exploding due to postwar investment in the industry.

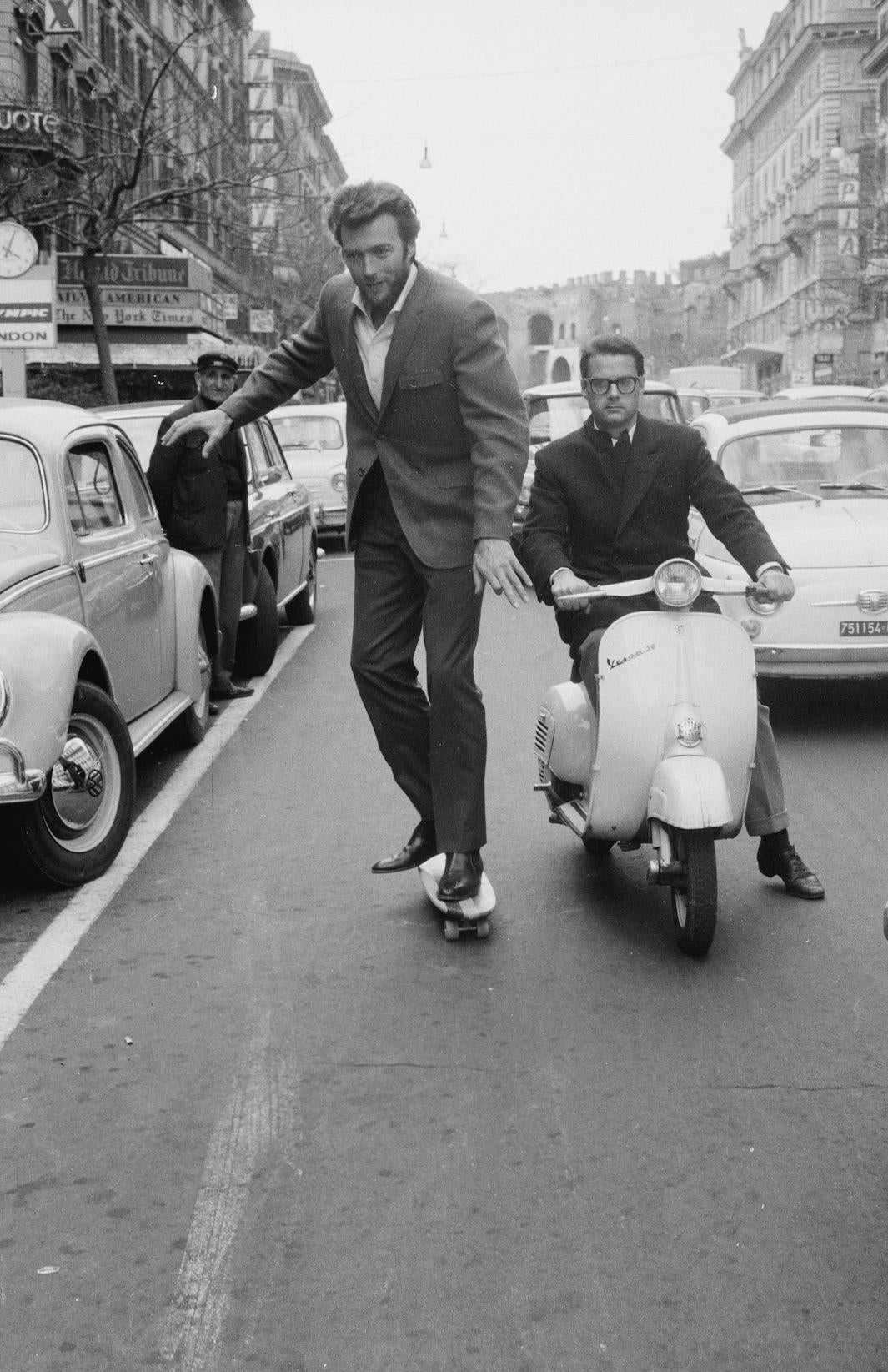

The book, Paparazzo: The Elio Sorci Collection, published by Roads this month, showcases the work of a photographer who helped define modern paparazzi photography, and, in a way, the notion of celebrity where the private lives of stars are infinitely knowable to the public.

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

“The great Hollywood studios of the ’30s and ’40s kept a very tight control on their stables of stars. The studio PR machines released highly stylized images of these stars. These became the defining concept of glamour,” Philippe Garner, a director at Christie’s and a leading paparazzi expert who wrote the introduction to the book, said via email.

“Sorci and his Italian contemporaries photographed celebrities in a new, informal way—on the street, in the back of a car, in a night-club. They did not change the movie business, but they opened up a whole new way of representing film stars in the press.”

In a new field driven by personality and instinct, Sorci’s “great energy and charm,” as well as his opportunism and savvy, made him a standout. His photo of photographer Tazio Secchiaroli being chased by the actor Walter Chiari helped cement the idea of paparazzi in the public’s imagination. Later, he snapped the image that finally confirmed the affair of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Though Sorci’s images did not always please his subjects, the relationship between press and celebrities during the time he worked was marked by a complicity that is not seen in quite the same way today.

“One earned his living from capturing the seemingly spontaneous moments that sold papers and magazines; the other enjoyed the limelight. If the paparazzo crossed the line and betrayed an affair or a sordid secret of any kind, clearly the relationship was soured. Today, those in the public eye tend to be far more wary of any but the most ‘star-friendly’ photographers,” Garner said.

Sorci and his peers not only invented the medium of paparazzi photography, Garner said, they pushed it to new limits by working spontaneously and “squeezing maximum mobility, flexibility and possibility from the equipment then available.” Today, “highly versatile digital technology, automated equipment, and speed of image transmission” have made the work of paparazzi technically much easier. Moreover, Garner said, the “vast majority” of today’s paparazzi shots are stage-managed set pieces, making Sorci’s unplanned and impulsive shots all the more alluring.

“Perhaps it is just nostalgia for a lost era, but somehow the stars and celebrity figures we see in Sorci’s images seem more seductive, more captivating than their modern equivalents.”

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press

Copyright Elio Sorci/Camera Press