- India

- International

The Ghat Keeper

A day in the life of: Ashok Kumar, 35 who has been cleaning the banks of the Ganga for 15 years.

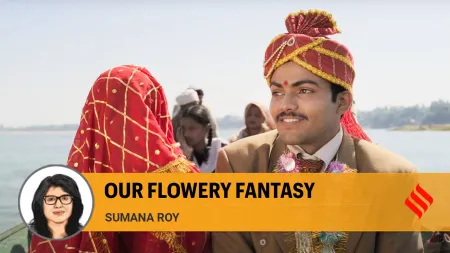

The Dashashwamedh Ghat is the “VIP ghat” and has seen high-profile visitors. (Source: Express photo by Vishal Srivastava)

The Dashashwamedh Ghat is the “VIP ghat” and has seen high-profile visitors. (Source: Express photo by Vishal Srivastava)

It’s 12 noon and the Dashashwamedh Ghat is quiet, with around two dozen devotees offering prayers and a few visitors enjoying the balmy winter sun on its steps. It’s the time of the day when the ghat and the river it lines, the Ganga, are the “least dirty”. But Ashok Kumar, the 35-year-old municipal sanitation supervisor, and his team of 15 workers can’t afford to take it easy. Holding their brooms and large garbage cans, they keep an eye out for flowers, polythene bags, gutka wrappers, paan stains, or chaat leaf plates that people throw into the river or carelessly leave behind on the steps.

Kumar and his team have been at work since 6 am, their day beginning with clearing the previous evening’s trash. “In the morning, the Ganga is at its dirtiest because of the large crowd at the Ganga aarti the previous evening,” says Kumar, who works between 6 am and 2 pm. He has had the job for 15 years, and earns around Rs 5,000 a month. His father used to do the same job before him.

There are 84 ghats around the Ganga in Varanasi, and Kumar supervises sanitation at five — Dashashwamedh, Prayag, Sheetla, Ahilyabai and Rajendra Prasad. Located close to the Kashi Vishwanath temple and known for its famous Ganga aarti, the around 60-foot-wide, 50-step Dashashwamedh Ghat is also known as “VIP ghat” because of its high-profile visitors. “Just yesterday, Nita Ambani visited the ghat. It was her birthday, and cricketers and film actors were here for the Ganga aarti,” he says.

Workers across three shifts clean the ghats each day — 6 am-2 pm, 2-10 pm, and 10 pm-6 am. However, hardly anyone works the last shift, says Kumar, the bulk of the cleaning done in the morning. So sometimes, when the work load is more, like during VIP visits, his team has to begin work as early as 4 am.

View more pictures of polluted Ganga in Varanasi

Among the lowest in the hierarchy of workers in the sanitation department of the Varanasi Nagar Nigam, Kumar is wary of giving details about the amount of waste left behind after such visits. “Well, we require more sanitation workers — before, to make the place clean for the VIPs, and after, because of the clean-up required. Like on this Sunday morning, a day after Ambani’s visit, some 50 sanitation workers cleaned the ghat.”

“The biggest VIP for me,” Kumar says, “is the municipal commissioner; he is my boss. If he comes visiting, we have to ensure the ghats look sparkling clean. Then, of course, the DM and other senior police officials.”

It’s a relaxed Sunday today though, and Kumar expects no high-profile visit. Just then, his friend, a sanitation caretaker of Kashi Vishwanath temple, comes to inform him of the DM’s visit. “DM sahab aa rahe hain. Meeting ke baad shaayad ghat ka daura karenge

(The DM is coming, and he might take a round of the ghats after the meeting),” the friend says.

Immediately, Kumar issues fresh instructions to his team. He asks some workers to take a round of the Rajendra Prasad Ghat, and others to inspect the adjacent Rana Mahal Ghat.

As the DM arrives and holds a meeting with police and municipal officials at a police post of Dashwashwamedh Ghat, Kumar spots a heap of polythene bags and coconut shells on his way towards Rana Mahal Ghat. “This is that shopkeeper’s doing,” he grumbles, pointing to a small shop selling puja paraphernalia. Kumar says it loud enough to catch the shopkeeper’s ear, but the latter doesn’t pay any attention.

Kumar then walks to one Nate Bhai, selling chana, and points to his empty dustbin. “Nobody drops the leaf plates in this bin. Why can’t you just put them in that bin?” he scolds. Nate Bhai, his mouth full of betel and gutka, too ignores Kumar’s outburst. “What can he say? His mouth is full. He’ll go spit at the ghat, and wait for us to clean up,” says Kumar.

Next, he pulls up a tea vendor for not keeping a plastic dustbin. “This soiled carton is itself garbage,” he tells him. “The plastic one got burnt yesterday. What can I do?” the vendor claims. “They will never listen to us,” Kumar shrugs.

Watching his team sweeping the length of the ghats, brushing away flowers, plates and polythene bags, he says, “By the time we reach the other end, the side we began from is dirty again. No matter how much we clean, you will feel nothing has been done.”

The situation is not very different in the river either. Two boatmen, who work on contract, row from one end of the ghats to the other, collecting flowers and other refuse. “The story is the same. They finish one round, and enough garbage has collected by then for the second round,” says Kumar. The boatmen also push away burnt corpses veering too close to the bank into the deep.

The Narendra Modi government has made cleaning the Ganga a top priority, and is contemplating drafting a law that makes it illegal to pollute it. The Supreme Court, too, recently pulled up the central and state pollution control boards for failing to take action against industrial units polluting the Ganga and assigned the task to the National Green Tribunal.

But Kumar feels all such measures “would come to nought unless attitudes change”. He points to discarded clothes lying on the steps, left behind by devotees, as well as a man leisurely lathering his body with soap in the water. “We can’t stop them. When we try to, they argue,” he says.

Kumar’s superior, who has come to receive the DM, agrees. “The only way to stop them is heavy fine and a couple of canes on their backs,” he says.

Noticing a woman member of his team lagging behind the others, Kumar asks her to be more efficient. “I’ve just fought with my father-in-law,” she tries to explain. Kumar hands her Rs 20 for tea. “They have their personal issues, they too need a break. There is no official off day for them, so they are given rest by rotation,” he says.

Despite the difficulties of his job, Kumar is proud of it. “When relatives and friends want some help at the ghat, say, getting a place in the aarti on crowded days, they approach me,” he says.

It’s past 2 pm and workers of the Ganga Nyas Samiti have begun washing the steps to prepare for the aarti. The DM has by now left, without even visiting the ghats.

Kumar’s shift over, he gets on his cycle and pedals 5 km to his home in Macchdori locality. “Holi is the only holiday we get in a year. Even on that day, Dashashwamedh is cleaned for the aarti,” he says. Kumar admits to differences at home over the early hours and lack of leave. He is married with a three-year-old daughter, and lives in a joint family with his parents and brothers.

Tomorrow is another of those early days. It is ‘Devotthan Ekadashi’, and he has to be at the ghat by 4 am.

“People will be thronging the ghat from the morning,” Kumar sighs.

HOW UNCLEAN IS GANGA

BOD or biochemical oxygen demand is the amount of dissolved oxygen needed by aerobic biological organisms in a body of water to break down organic material. Higher the BOD, higher the pollution in the water sample.

22 of the 55 locations along the 2,525-km-long Ganga have a BOD higher than the permissible limit of 3 mg/litre. That makes the water unfit even for bathing.

26 locations show BOD levels between 2 and 3 mg/litre, which means that the water in these places can be consumed, but only after treatment and disinfection.

3 locations along the river — Rishikesh in Uttarakhand, and Nabadweep and Tribeni in West Bengal — have BOD levels lower than 2mg/litre, which means the water can be consumed without treatment.

0 is the BOD at Gangotri, the source of the river

(From data gathered in 2013 by The Indian Express under the RTI Act)

May 07: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05