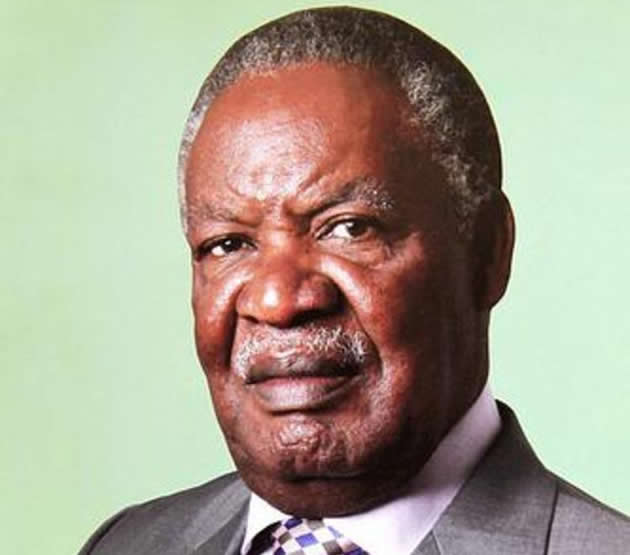

Sata: The King Cobra sleeps

Stephen Chan Correspondent

Michael Sata, who has died aged 77, was the fifth president of Zambia during the half century since the country became independent.

A charismatic, forceful but controversial figure, he led the third political party to attain office. The first had been Kenneth Kaunda’s United National Independence party (UNIP) which ruled until 1991, when multi-party elections were forced on Kaunda by civic action.

He was replaced by Frederick Chiluba’s Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), and it was as members of the MMD that Levy Mwanawasa (2002-08) and then Rupiah Banda succeeded to the presidency.

Sata led his Patriotic Front (PF) to victory in the 2011 elections — the fourth time he had contested them.

These moves may suggest that Zambia had witnessed changes in the ruling elite and the exercise of power, but this impression would be somewhat misleading.

Sata in fact represented continuity, having served in the 1980s as the extremely successful governor of the capital city of Lusaka under Kaunda.

He went on to become minister of local government, labour, and health under Chiluba.

It was at this time that he became known as King Cobra, for his ruthlessness towards opponents.

Sata did not serve in the Mwanawasa and Banda governments, because he had sought the succession from Chiluba and was disappointed when it went to Mwanawasa — another president who died in office and whose final illness, like Sata’s, was carefully but not completely hidden from the Zambian public.

After he left the MMD, Sata formed the PF and contested three elections without success. The first, in 2001, was a disaster for him, with his party attaining only one parliamentary seat. However, his doggedness showed through: he regrouped, and the 2006 elections were noted for two spectacular actions on his part.

The first was to liken incumbent president, Mwanawasa, to a cabbage. Sata ripped a cabbage to shreds at a rally — both a symbol of his intent to tear the presidency from Mwanawasa and to remind voters of the rumours that Mwanawasa had been injured in a car accident in 1992.

It was a crude and offensive gesture, but renewed his reputation for ruthlessness and decisive action.

At those elections he also attacked Zambia’s Chinese investors, creating a diplomatic storm over disastrous Chinese management of certain copper mines.

He threatened to recognise Taiwan, the non-communist Republic of China, and prompted Beijing into a rare moment of panic, threatening to cut diplomatic relations in the event of Sata’s election.

When Sata did finally win in 2011, it was with the moderating force of Guy Scott, who became both vice-president and the man in charge of relations with Chinese investors.

Scott, who now assumes the interim presidency pending elections within 90 days, has handled these responsibilities with care and finesse. Chinese construction firms are visible in many large Zambian cities as the country enjoys economic success and a building boom.

Sata’s period as president saw marked economic growth, but this depended greatly on increases in prices for minerals such as copper: there are clear signs that the boom has peaked and may now be declining.

His scathing attitude towards opponents continued to surface and he never lost his King Cobra tag.

Nonetheless, he made a positive contribution in promoting the intercommunal spirit favoured by Kaunda. The choice of Scott as president is a case in point.

Nowhere else in majority-ruled Africa has a white man succeeded, even if temporarily, to the presidency.

Sata had difficulties with the secession movement in the Lozi kingdom in western Zambia, and his political opponents accused him of human rights abuses, even bringing a complaint to the attention of the Commonwealth secretary general, Kamalesh Sharma, based on alleged breaches of the Harare Commonwealth Declaration on Human Rights.

Sata responded to his opponents and detractors with the robustness that might be expected from someone who had laboured as a manual worker, policeman, London station porter, and even as a taxidermist.

Born in Mpika, in the north of the country, at a time when it was under British rule as Northern Rhodesia, he had little early education, but later studied privately and gained a degree from the unaccredited Atlantic International University.

Unlike Kaunda, he never postured as an intellectual.

He saw himself brusquely and bluntly as a man of the people, and used his rough voice, gravel-like from chain-smoking, to great oratorical effect in his no-nonsense speeches.

His death, from an undisclosed illness following a period in a London hospital, offers the possibility that Zambia may finally have a new generation in power, even if in the curious continuity of Zambian politics, it has acquired all the characteristics of the old.

He is survived by his wife, Christine (nee Kaseba), and eight children.

Michael Chilufya Sata, politician, born 6 July 1937; died 28 October 2014. — The Guardian.

Comments