FIFA movie is little more than PR spin for Blatter

Governing body's self-indulgence won't earn it any goodwill

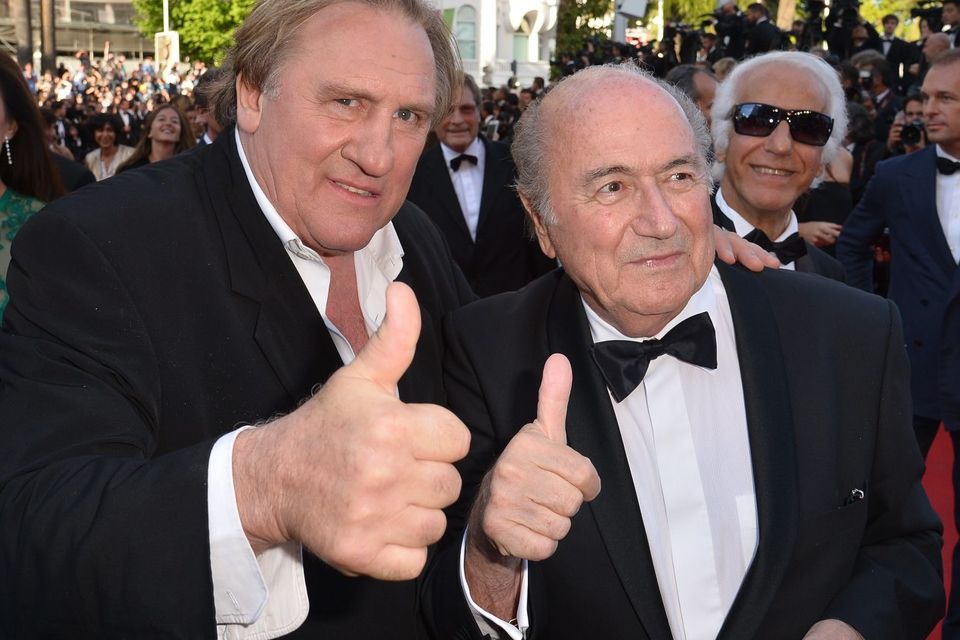

French actor Gerard Depardieu (L) and FIFA President Sepp Blatter give a thumbs-up as they arrive for the screening of the film "United Passions" at the 67th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, southern France, in May 18

It is fair to say that Sepp Blatter will not be gatecrashing any selfies at next year's Oscars. Indeed, no one involved in FIFA's attempt at a box-office blockbuster, United Passions, should be winning awards any time soon. Considering the film tracks the development of a sports governing body, with all the excitement of arranging tournaments and striking marketing deals, that does not really come as a surprise.

Yet at a cost of €24m, someone, somewhere, obviously thought documenting FIFA's apparent progress through the 20th century over one hour and 45 minutes was a good idea. Perhaps in the gilded corridors of Zurich they still do, but the recurring sensation while watching "the story of FIFA's foundation and subsequent globalisation of football" is predominantly one of bemusement.

FIFA contributed €21m towards the film which, as many critics have pointed out, equals the annual budget for its Goal programme to fund football projects in poorer countries. It premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May and was produced by two external companies - Leuviah Films and Thelma Films. The director was Frederic Auburtin, who previously worked on The Man in the Iron Mask.

It is all the more perplexing given the cast of actors. Blatter is played by Tim Roth - yes, Tim Roth of Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction - while Gerard Depardieu, as Jules Rimet, is the protagonist for the opening half. Sam Neill plays the former FIFA president, Joao Havelange.

Spoiler warning, though; this is not a film about corruption. Far from it. United Passions may touch on areas of murkiness within FIFA but even Havelange's misdemeanours - accepting lucrative bribes through marketing contracts - are only skirted around. There is no Jack Warner; there is no Mohamed bin Hammam; there is no Ricardo Teixeira.

"Since this is not an investigative movie the authors chose to make it a grand epic," said Louise Maurin, Leuviah chief executive. "We consider the film excellent but in the cinema it is sometimes difficult for a film to find its audience. President Blatter was touched by and satisfied with the film." This is a biopic that positions FIFA's founders and executives as the stars, struggling to arrange the first World Cup in 1930 before financial hardship strikes in the 1970s. It is truly nail-biting stuff but, rest assured, Blatter and FIFA emerge triumphant, overcoming edge-of-your seat administrative hurdles and defying the meddlesome media.

Depardieu, as Rimet, is the early hero, bringing the first World Cup to Uruguay where the actual football consists of a 20-second montage. His last act is awarding the trophy to the same country at a stunned Maracana stadium in 1950 before Havelange takes centre stage, portrayed by Neill as a smooth operator who secures his place as president by wooing African members. But all is not well at FIFA headquarters. Money is tight and they need a man who can steer them away from looming disaster. Enter Blatter, who first appears in a Sion pub, revealing that he has been offered a job in football: "It can't be any harder than watches," he muses.

And so Blatter begins his climb to the top. "He is apparently good at finding money," says Havelange at a meeting in which he furiously demands more income sources from his staff, slamming a desk and declaring: "I don't care if you call on Brezhnev or Castro or Mao!"

Blatter strikes lucrative deals with Adidas and Coca-Cola, progressing from a ham sandwich-eating newbie in a suspect chequered jacket to an experienced FIFA blazer. He eventually succeeds Havelange and, despite grumblings from his executive committee, insists - without a trace of irony - that "the slightest breach of ethics will be severely punished". The film's reception has been muted, given that it has only been released across a small number of hand-picked countries. In Russia, hosts of the 2018 World Cup, it made around £100,000 at the box office. Portugal's gross takings were just over £4,000, Serbia's £2,000, while the profits from Hungary, Slovenia and Ukraine were minimal. Jerome Valcke, the secretary general, described the film as "open, self-critical and highly enjoyable" in a letter to FIFA members and said it was "part of FIFA's reform process . . . to promote more direct communication with the world".

But in a year when the governing body's reputation has taken a significant battering, it is difficult to comprehend how a multi-million pound film, albeit one that was first mooted in 2004 to coincide with FIFA's centenary, will earn much goodwill.

However, the PR expert Mark Borkowski believes there was a specific plan in place when rolling out the red carpet in chosen locations. "It was a glorified infomercial that was aimed at certain countries. It did feel like a totalitarian regime's information film."

He added: "The intention of it is probably to galvanise their brand in certain places across the world. But most football fans in this country would look at this and snigger." The only laughs United Passions is likely to receive are ones of incredulity. But for Blatter and co the criticism is unlikely to be of major concern. As Roth says when warned by a colleague that FIFA is dragging his name through the dirt: "I grew up on a farm. I have no fear of mud."

Observer