Dreaming

Dream Scanners

Can brain imaging technologies be used to decode people's dreams?

Posted October 20, 2014

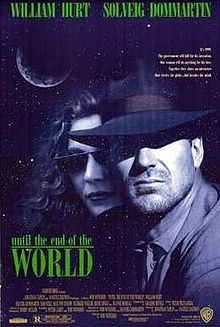

In the 1991 film Until the End of the World director Wim Wenders imagined a near-future in which people use videophones, portable computers, facial recognition software, robotic vehicles, and many other technological marvels that have in fact become regular features of 21st century life. The greatest innovation of all is saved for the final section of the film, when a specially designed biochemical camera is found to have the power of recording people’s dreams and then replaying them on a video screen.

Naturally, the CIA is trying to steal it.

The movie takes a long time to reach the scenes with the dream recorder (the original director’s cut was four and a half hours long; the commercially released version was two and a half hours). The final, apocalyptic setting is somewhere in the Australian outback, a place evoking ancient myths of timeless dreaming. The power of the dream decoding device is literally mesmerizing, as the characters become totally consumed with the infinitely creative spectacle of their own dream lives.

How close are modern scientists to fulfilling this alluring vision of a scanner that can read and reproduce people’s dreams?

It might seem we are almost there, based on the findings of a research study published in 2013. Yukiyasu Kamitani and his colleagues at the ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto, Japan used fMRI brain scanning methods to compare people’s brain patterns when they dreamed of a particular object (such as “car”) and when they looked at that object in waking life. They used these correlations to assess the brain patterns in new dreams and make predictions about whether the object was or was not present in each given dream. In an interview with Mo Costandi of the Guardian, Kamitani said, “We built a model to predict whether each category of content was present in the dreams. By analyzing the brain activity during the nine seconds before we woke the subjects, we could predict whether a man is in the dream or not, for instance, with an accuracy of 75-80%.”

This is fascinating and important research showing that the same high-order brain systems involved in waking visual perception are also central to dreaming experience.

Most of the media attention surrounding this study was directed toward its futuristic implications. Less attention was given to the critical questions we should reasonably be asking about these advancing technologies.

First, what about REM dreams? It’s important to note the researchers used the fMRI scans on people during the hypnogogic state between waking and sleeping. Hypnogogic dreams tend to be rather brief and trivial, in contrast to the longer, more symbolic and vivid dream experiences usually associated with REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. It would be wise to refrain from making claims about all dreams based only on data from sleep onset. Unfortunately, gaining comparable data from REM sleep will be very difficult given how much more complicated and intense the brain’s activities are during REM. Huge technological leaps will be required before researchers can perform a detailed fMRI scan of people’s brains while they are dreaming in REM sleep.

Second, what about the non-visual qualities of dreaming? Dreams are not merely linear strings of visual images. They are multi-sensory, emotionally rich, cognitively complex phenomena that emerge out of a densely-woven tapestry of personal life history and cultural traditions. Dreaming is a “whole brain” experience. Vision is often the most important sensory modality, but the fullness and depth of the dream world derives from more than one channel of perceptual information. A device that cannot account for the holistic, integrative processes of the brain during sleep will not be able to faithfully represent the experiential qualities of a person’s dreams.

Third, what about the obvious potentials for abuse? In Wenders’ movie the Aborigines flee in horror when they realize what the mad scientist (Max Von Sydow) is trying to do with the device and its “Dream Tap” program. The CIA’s interest in dream decoding is never specified, but 20+ years later we can easily imagine how this kind of technology could be put to malevolent purposes by the surveillance state: interrogating prisoners, controlling the minds of enemies, monitoring ordinary people for signs of possible dissent and disobedience…

This is why every time a new development is reported in brain scanning technology—and dramatic innovations will happen with increasing frequency, thanks to public-private partnerships like President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative—we should ask pointed questions about the moral implications and potentials for abuse. The more quickly and clearly we anticipate the possible dangers of using such technologies, the more likely we can find effective ways to protect against them

The best way to start that effort is with the cardinal principle of ethical dream research: Respect the dreamer. In practical terms this means new technologies should guarantee the dreamers have a meaningful role in deciding who has access to their dream data, how much they can access, what they can do with it, and for how long. This principle should be built into the digital architecture of any device designed to record and analyze people’s dreams.